Beneath a Still Surface

The keen insight and quiet force of Rav Gershon Edelstein

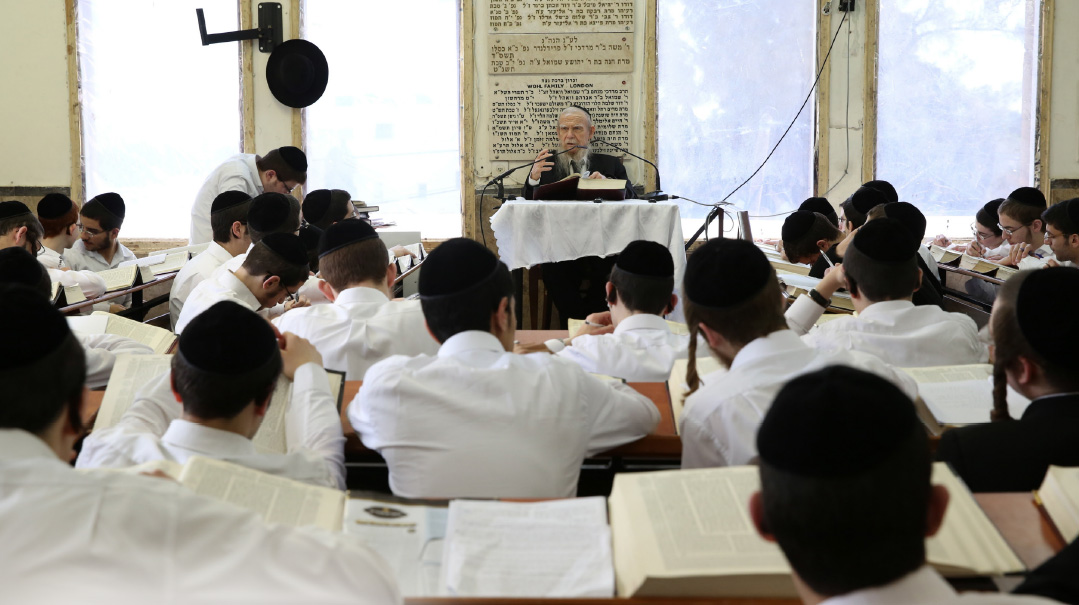

Photos: Itzik Belinitzki, Flash 90

The plastic partition that rests between Ponevezher Rosh Yeshivah Rav Gershon Edelstein and his visitors is symbolic in the sense that he can see them perfectly even as he exists in a sublime world, somewhat removed from the commotion.

Minchah has just come to an end, and the small microphone he uses to communicate with visitors is powered on.

Rabbi Noach Paley is first in line, and through his organization, Lev El Haneshamah, he is on the frontlines of the contemporary chinuch scene. He comes bearing the questions, worries, concerns, and anxieties of so many parents, and the Rosh Yeshivah receives him and all he carries with a gentle smile.

This is who Rav Gershon Edelstein is and what he does. He is mechanech Jewish children.

Those familiar with the Rosh Yeshivah’s approach to giving guidance know to come with no prior expectations. Recently, when asked for a letter in support of a prominent organization led by one of his close talmidim, Rav Gershon refused. This was surprising, since it’s a legitimate, effective organization. The request was then made for a letter of brachah, but Rav Gershon stood firm. Not even a letter of brachah.

After the disappointed delegation filed out, the talmid, who’s close to Rav Gershon, reentered the room. He knew that Rav Gershon’s every decision is calculated and he asked the question. “Why, Rebbi? This refusal, too, is Torah, and I must learn it.”

Rav Gershon explained himself. A competing organization had recently asked for a letter of support, and for various reasons, he felt unable to accommodate them.

Rav Gershon, who is nasi of the second organization, and well-acquainted with its vital work, continued, “I thought about how they would feel if they saw that I signed a letter for you, and decided that it wasn’t worth it.”

The bigger picture. Rav Gershon fields the questions and concerns of generations with astounding clarity and insight, honed in the very same room where he’s given shiur to 17-year-olds for seven decade

It’s been a tumultuous few years for the Torah community in Eretz Yisrael, and Heaven has sent them shepherds to guide them accordingly.

Rav Gershon brings his unique style of leadership, one crafted over decades as a leading maggid shiur. He takes in the entirety of the picture, and evaluates every single detail. If there are documents to sign or review, he will read each one several times, asking pointed questions.

This practice has made him uniquely suited to answer chinuch questions, for his insight into chinuch comes from asking and answering, from the real-world experiences of the masses who have been coming to Rechov Raavad for guidance.

At chinuch seminars, the Rosh Yeshivah astonishes maggidei shiur a third of his age with his insight into today’s bochurim, an insight honed in the very same room where he has been saying shiur to bochurim for over 70 years, bli ayin hara.

He is unique in that role as well. Roshei yeshivah who say a daily shiur into their nineties are few, and if they do it, it is generally a shiur klali or private shiur for select talmidim.

But Rav Gershon says shiur to boys who are 17 years old, as if he weren’t the gadol hador, dealing with questions of life and death from across the world on a regular basis.

It’s what he signed up for at the very beginning, when he came to yeshivah.

And it’s only been this yeshivah for him, for there has never been another.

He’s in his late nineties, but Rav Gershon still walks without the aid of a cane to his daily shiur for the shiur alef students of Ponevezh

Rav Tzvi Yehuda Edelstein arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1934, accompanied only by a daughter and his two sons, Gershon and Yaakov, for his rebbetzin had passed away in Russia. A relative in Ramat Hasharon suggested they settle near him, and they moved into an empty chicken coop, using discarded crates as furniture.

The father and his two sons sat and learned, Torah and more Torah. Chumash, Nevi’im and then Shas — all of it, with Rosh and Rif. On Shabbos, they would learn the Rambam on the masechta they were learning. There was no bein hasedorim and no bein hazmanim.

Rav Tzvi Yehuda had become enthralled with the author of a sefer he had discovered in shul, and he traveled to Bnei Brak to meet the relatively unknown talmid chacham, Rav Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz, the Chazon Ish. He took his bochurim to meet this new mentor, and the Chazon Ish spoke to them about the masechta they were then learning, Yevamos.

He was impressed with what they knew, and how they knew it, and so they continued learning together with their father. Then the Ramat Hasharon rav moved to Jerusalem and Rav Tzvi Yehuda was asked to take his place, leaving him with less time. As his workload grew, his sons went to learn in Lomza. But they kept the Chazon Ish’s guidance in mind.

“You already have a derech halimud from your father,” he told them. “Make sure you do not lose it in yeshivah!”

Two years later, Rav Shmuel Rozovksy paid a visit to Ramat Hasharon. The Ponevezher Rav was opening a yeshivah and the two Edelstein bochurim were invited to join.

The yeshivah opened in 1944 with six bochurim, among them Yaakov and Gershon Edelstein. Two years later, the Ponevezher Rav asked young Gershon to learn with some new talmidim, among them survivors from the fires of Europe, and the bochur became “Reb Gershon” to them.

In time, the Chazon Ish suggested that Rav Gershon Edelstein become an official maggid shiur in the yeshivah, and that is the job he still fills with distinction.

The clarity of his shiurim, the ability to anticipate the questions that might be troubling his listeners, and the purity and middos of the maggid shiur himself made him “the” maggid shiur for that age. Roshei yeshivah across the country made it a priority to send their own sons to Ponevezh specifically to learn under Rav Gershon.

His printed shiurim became must-haves for aspiring maggidei shiur, both for what he says and for what he chooses not to say, and throughout the years, he has been the final authority on so many chinuch questions, the one trusted by his contemporaries, the gedolei hador, to make weighty decisions.

Now, as we sit in the Rosh Yeshivah’s home, questions that have arisen for the devoted chinuch personalities of Lev El Haneshamah are raised. The Rosh Yeshivah listens calmly, hearing the questioner out on each one.

As an organization that supports parents and mechanchim, we are often asked: A bochur is weak in learning, and has all sorts of challenges. Should we try to send him to a higher-level yeshivah in the hopes that he will work his way up? Or should we “settle” on a weaker yeshivah, where at least he will be safely within the system, without a real desire to leave?

The Rosh Yeshivah’s answer is firm:

“Does the weaker place have an atmosphere of yiras Shamayim and good middos? If there is yiras Shamayim, and he feels better there, then it’s very good.”

There are bochurim who find it hard to learn. They say they find no taam, no flavor in it, and they don’t enjoy it. What should be done with them?

“A bochur like that should learn Gemara only with Rashi. He shouldn’t aim for iyun, for depth, but rather he should learn on a simple level. That type of learning is very attractive and inspires a desire to know more.”

But in yeshivah, the standard is iyun.

“He will learn b’chavrusa, only Gemara. With Rosh, with Rashi, maybe Tosafos. And he should review his learning often… chazarah (with its accompaniment feeling of mastery) brings a tremendous sense of fulfillment.”

The boy who grew up in a chicken coop in Ramat Hasharon eventually found his place on the mizrach vant of Bnei Brak, sharing the reins of leadership with the generation’s greatest luminaries. With Rav Chaim Kanievsky, Rav Aharon Leib Steinman, and Rav Elazar Menachem Shach z”l

Hundreds of young bochurim come each Elul to the Ponevezher Yeshivah and hear a shiur from Rav Gershon, who delivers it just like he did 50 and 60 years ago to their fathers or grandfathers. In the first months of the winter zeman, he welcomes groups of six or seven bochurim each afternoon in his home. He asks each one his name and who his chavrusas are for each of the three sedorim. Later, he speaks to them about the sugya being studied in the yeshivah and suggests that they say something about the shiur, offering their own insights, questions, or chiddushim.

In Ponevezh, close oversight of each bochur isn’t part of the culture, but Reb Gershon has appointed avreichim to keep an eye on the bochurim in his shiur. They are the ones who make sure each one has a chavrusa, for example, and they are in charge of making sure that each boy has an address and a listening ear to also take care of the “small things” that can disturb a bochur while he is learning.

During his receiving hours, when many people come to seek advice and brachos, the number of people sometimes exceeds the strength of the Rosh Yeshivah, and some are deferred to a different day. But when a talmid from his shiur comes, he’s accorded priority status and will be allowed in before anyone else.

Rav Gershon might be a gadol hador, but he was a maggid shiur in Ponevezh first.

Since the Covid outbreak two years ago, the Rosh Yeshivah has adhered very closely to the experts’ advice regarding social distancing. He sits on one side of a plexiglass partition while the talmidim sit on the other side. In order to be able to communicate clearly without the need to raise voices, sophisticated microphones were installed, making it possible to communicate calmly and clearly.

A few years ago, the Rosh Yeshivah did not feel well one day. It was unusual for him to miss shiur, but he was simply too weak. Suddenly, there was a knock at the door; a talmid who was with the Rosh Yeshivah wanted to open the door. The Rosh Yeshivah stopped him, and got out of the bed himself. He went to the door and told the person who was knocking: “I don’t feel well, please, if you could come another time.”

A few minutes later, there was again a knock at the door. Again the Rosh Yeshivah got up, went to the door, and said to the knocker, “I don’t feel well, if you could please come another time.”

The talmid could not contain himself and asked: “Why does the Rosh Yeshivah have to keep getting out of bed? I can tell people at the door that the Rosh Yeshivah doesn’t feel well and that there are no receiving hours today.”

“There is an older bochur who made an appointment to speak to me today,” Rav Gershon replied, “and I think he will feel better if I answer the door myself. It will give him respect and he will see that I was expecting him.”

A young man close to the Rosh Yeshivah was deliberating whether to move to a different area, and asked for advice. He prepared a list with 15 considerations for each side in his deliberations. At the bottom, he added a puzzling consideration: “I once stayed in the area of the apartment and the neighbors claimed that my children made noise when they were playing in the yard.”

The Rosh Yeshivah read this, recoiled, and asked: “They made noise and it bothered the neighbors? Run and ask a rav!”

The young man asked a rav who ruled that there is no problem with children making the appropriate noise when playing. He went back to the Rosh Yeshivah with the rav’s ruling, but Reb Gershon again read the last piece, and recoiled once again. “It disturbs the neighbors! It bothers them… chalilah! Stay far away from them! Don’t cause pain to other Jews!”

One day, an avreich asked him a sensitive question. A teacher had been fired in one of the Chinuch Atzmai schools, and his wife had been asked to take her place.

“Chalilah!” the Rosh Yeshivah exclaimed. “Jewish blood is still bubbling in that classroom…”

“But the teacher was fired without any connection to my wife! She was fired before my wife was offered the job,” the avreich claimed.

“That is true,” the Rosh Yeshivah replied, “and they probably had no choice but to fire her… But an avreich like you, nu, you have to stay sensitive. Jewish blood was spilled there!”

Any person who comes to ask Rav Gershon’s counsel will be greeted pleasantly with respect and courtesy. His question will be treated with seriousness and focus.

Rav Gershon’s youth in the farmtown of Ramat HaSharon trained him early on in how to speak to all sorts of people, and it makes no difference how the visitor is dressed or with what accent he speaks. A Jew is royalty, and in this apartment on Rechov Raavad, he is treated with utmost respect.

He may be the gadol hador, but he was a maggid shiur in Ponevezh first. Seven decades later, he’s still at his post, teaching, encouraging, and connecting with a new generation of talmidim

How much of an emphasis should be placed on insisting that yeshivah bochurim wear a hat and jacket when they’re out of yeshivah, especially a bochur who claims that he has a hard time with it?

“The importance of a yeshivish appearance needs to be explained to him.”

(This reflects a major element in the Rosh Yeshivah’s approach to chinuch, one often repeated at chinuch seminars at which he speaks. It is unfair, he will explain, to say a talmid or talmidah doesn’t want to do something, or rejects an idea, if that concept was never properly explained to them. The onus of explanation is on the one trying to transmit the idea, and with proper preparation and work — as the maggid shiur well knows — anything can be made clear.)

There is a boy who doesn’t want to go to davening, and prefers to stay at home. Is there anything to be gained by pressuring him to go to shul?

“No. Force will not do, but in general, the natural way is that a child will do what his father does…”

Parents ask what to do with children who struggle to sit at the Shabbos table or the Seder table for a long time. Should they be allowed to play during this time?

“It is not possible to parent effectively through coercion.”

Somehow the teens of the 21st century sense that this vaunted scholar close to a century old can intuit their goals and doubts

The Rosh Yeshivah is known for his strict adherence to the sedorim in the yeshivah, and for his scrupulous efforts not to miss any of them. To this day, he is the zakein v’yoshev b’yeshivah, learning diligently like a young bochur. Even during bein hazmanim, there are shiurim in this home, attended by about 50 talmidim. The shiur continues, with all its participants, each day — even on the day of bedikas chometz.

Once, during bein hazmanim of Av, which he spent at the home of his grandson Rav Aharon Weiss, one of the roshei yeshivah of Mir Brachfeld, Rav Gershon was informed that at five o’clock, a car would be ready to take him wherever he needed to go.

He responded in surprise: “Five? But that’s in the middle of seder!”

Though he lives within the four walls of the beis medrash, Rav Gershon is aware of the fact that there are yeshivah bochurim in sensitive situations who require professional treatment. He often advises people to go for help, even beyond the community: When a professional is necessary, he says, one should seek the one best suited to help them.

His hesped at the levayah of Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l, was dedicated to imbuing the importance of learning mussar, each person according to his level and his inclination. Millions of Jews saw or heard, through live hookups, the call to refine our middos and strengthen the connection with HaKadosh Baruch Hu through learning mussar.

He himself is testimony to the fact that mussar elevates and refines a person.

Talmidim have a hard time recalling a single instance in which the Rosh Yeshivah grew angry or lost patience with someone, despite having dealt with many difficult and emotionally disturbed people over the years.

Once, while Rav Gershon was learning b’chavrusa with a talmid, a Jew in a very poor emotional state came to visit. For half an hour, he vented his anger and frustration about this person and that problem. Although missing seder bothers the Rosh Yeshivah, he was quiet, listening closely to what the person was saying.

“It’s a mitzvas aseh of gemilus chesed, which cannot be done through others,” he later explained to the chavrusa. “There is no one else willing to listen to him.”

One of his talmidim related that his bond with the Rosh Yeshivah was forged when he once asked to learn with Rav Gershon b’chavrusa on Shabbos. At the beginning of their learning session, the Rosh Yeshivah asked the bochur to tell him the names of the bochurim in the yeshivah who he thought might need encouragement, so that he could provide that encouragement.

The talmid replied with a smile, “Me! I need encouragement!”

In response, the Rosh Yeshivah smiled and said, “Nu, so you are able to take encouragement for yourself. I am asking about someone who cannot encourage himself, and needs encouragement from the outside. I don’t know the bochurim all that well, but you can help me on this matter.”

At the end of their learning session, the Rosh Yeshivah asked that every Shabbos, this bochur bring at least two names of bochurim who need encouragement. The arrangement continued for two years.

Rav Daniel Jacobowitz, rosh yeshivah of Nachalas Binyamin, related that the Rosh Yeshivah once told him in the name of Rav Schach ztz”l that the job of every rosh yeshivah and maggid shiur is to enter the beis medrash in the morning thinking about whom he can do good for today.

Rav Gershon’s nephew, Rav Avraham Diskin, rosh yeshivas Ohr Shmuel in Jerusalem, relates that there was a bochur who learned in his yeshivah with tremendous hasmadah, and after a few years, he moved to Ponevezh. When Rav Diskin next visited his uncle, Rav Gershon said, “I noticed that this bochur’s hasmadah is not natural. I’m afraid that if he continues this way, he might fall.”

Half a year later, indeed, this boy collapsed and was unable to return to learning for several months. Rabbi Diskin recalls, “I was amazed at the fact that I knew the bochur for three years and it didn’t enter my mind that his hasmadah was not natural, while the Rosh Yeshivah barely knew him for a few months, as one of hundreds of bochurim in the shiur — and from the start, he noticed that something in his incredible diligence seemed forced.”

The path to a child’s heart. Rav Gershon counsels parents and mechanchim never to take the route of force — use pleasantness and a personal example to nurture good behavior

Rav Gershon’s official induction into public life came on the 17 Iyar 5776/2016, when the first meeting of the presidium of the Vaad Hayeshivos took place in his home. Rav Aharon Leib Steinman, who was the nasi of the Vaad Hayeshivos at the time, said he felt too weak to lead it, and asked that the meeting take place in Rav Gershon’s house instead.

Later, he was given leadership of the Moetzes of Degel HaTorah as well. Since the passing of Rav Steinman in Kislev 5778, the leadership was divided between Rav Gershon, and Rav Chaim Kanievsky, as both gedolei hador passed the reins of leadership from one to another and sought each other’s counsel before rendering a decision.

Rav Chaim even saw himself as a “talmid” of sorts of Rav Gershon, since he was a few years younger. Rav Chaim used to relate, “When I came to learn in Lomza Yeshivah in Petach Tikvah, my uncle, the Chazon Ish, told me to speak in learning with the good bochurim in the yeshivah. Among the names the Chazon Ish mentioned was Rav Gershon Edelstein. He said to me, ‘Dos iz der dmus fun der yeshivah — this is the leading figure of the yeshivah.’ I didn’t dare approach him, because at the time, Rav Gershon was considered the illui of the yeshivah, and I was too in awe of him.”

Recently, there was a gathering in Bnei Brak by an organization of bnei yeshivah, ahead of the beginning of the zeman. In the heading of the kol korei that was issued ahead of the event, it stated that every yeshivah bochur had to attend the event. They brought the letter to the Rosh Yeshivah to sign.

But he reviewed it and asked, “What does ‘mandatory attendance’ mean? Who made it mandatory? We have to write that it is worthwhile to come, but not mandatory…”

At a meeting attended by a number of gedolei Yisrael, each one of them spoke briefly, so as not to waste precious time. Then one of the speakers began a long-winded speech, in which he spoke at length about the organization he was involved in. After speaking for five minutes, when the other speakers did not exceed two minutes, someone gestured to him to cut it short. He nodded and continued speaking… A few more minutes passed, and one of the people present put a hand on his shoulder, so that he should understand the hint. The speaker did not understand hints, and only after many long moments did he finish.

The entire time, Rav Gershon was focused on the speech, listening attentively.

“It was so interesting,” he said. “What a nice derashah!”

Later he asked the speaker for more details about the organization, though it was clear that the Rosh Yeshivah already knew all the details and the stories. Apparently, he had noticed that they were pressuring the man to finish, and he wanted to restore the man’s dignity.

The Rosh Yeshivah gives a special shiur in Mishyanos Taharos to his extended family. It takes place each Motzaei Shabbos in his home, where there are many other shiurim in all areas of Torah. His weekly shmuess takes place each Tuesday evening, at home; it is widely renowned and attracts mechanchim and community leaders. In this shmuess he often speaks about current issues on the agenda, and the media waits, anxiously following to hear what he has to say about relevant issues each week.

Because he is aware that his words are publicized, Rav Gershon is exceedingly careful not to say things that could be misinterpreted, intentionally or not. Sometimes, he will be asked a question, and, despite not having been raised at a time when media operated with such lighting speed as today, he will choose not to answer at all, or at least to refer the questioner to someone else, since he well understands the dangers of publicity.

In Tammuz 5744/1984, there was a gathering in Jerusalem to mark 35 years since the passing of Rav Shmuel Rozovsky ztz”l. The organizers invited Rav Gershon to deliver the main shiur, and Rav Yehuda Adess, rosh yeshivah of Kol Yaakov, to deliver the main address.

Rav Gershon’s nephew, Rav Eliyahu Diskin, who at the time lived in Jerusalem’s Bayit Vegan, accompanied Rav Adess on his ride home.

On the way, Rav Adess said admiringly, “The tzibbur does not realize who Rav Gershon is. In the accessible way he speaks, which everyone understands, he makes it seem like everything is simple and easy. But in reality, there is unbelievable depth here, intense sevaras, important fundamentals. I could make four shiurim klaliim from the words he spoke tonight.”

Rav Adess once told those accompanying the Rosh Yeshivah his opinion on Rav Gershon’s stature: “For years already I think that we have to recite ‘Baruch shechalak mikvodo l’yereiav’ on Rav Gershon.”

His word is law. Even among the leaders of the Torah world, the rosh yeshivah from Rechov Raavad wields unquestioned authority

The questions get a bit more complex.

Some ask if it is right to play with children, to devote time for them, even when it comes at the cost of the father’s learning time. Is this bittul Torah?

“Let him take walks with the boy, and tell him stories of tzaddikim, or history.”

How should a child in cheder who learns very well but offends and hurts and teases others be treated?

“He needs to be told that he is harming his own good name.”

Is it right for a cheder to dedicate time to teaching children how to behave and how to treat friends, and to devote lesson time to these issues?

“Certainly, this is something that needs to be done.”

In our organization, Lev El Haneshamah, we try to place children in schools. Sometimes we deal with situations in which the families are modern, but the child is very pure and sincere. Should the hanhalah be told about the choices of the parents? There are other parents in the school who wouldn’t want children from homes with low standards, and perhaps it’s important to share this information?

“So why should the child not be accepted?”

There are countless stories of roshei yeshivah, maggidei shiur, and chinuch figures who come to seek the Rosh Yeshivah’s advice, and they say that he is firmly opposed to expelling a bochur, embarrassing a bochur, or punishing him in a way that will shame him. Before such a thing can happen, he urges them to make sure that every other option has been exhausted. There is no such thing as giving an order with the wave of a hand “he’s not suitable,” “he is a bad influence,” “throw him out of yeshivah.” Every case is discussed in context, very carefully, and it drains him of energy, sometimes to the point of exhaustion.

A well-known talmid chacham who is heavily involved in chinuch tells Mishpacha: “A colleague and I once sat with the Rosh Yeshivah discussing how to handle two bochurim, and he gave us clear and specific direction on how to act. The next day, at 8:30 in the morning, he called me and my colleague, and asked that we come back.

“When we came to his home, the Rosh Yeshivah said with a smile that the plans had changed.

“ ‘After you left the house,’ he said, ‘I realized that if Ploni were to speak to the bochur, he would probably react like this, and if so, there would be no significant benefit. Therefore, it’s important that Almoni be the one to speak to him, and then the bochur won’t feel chastised, but rather will receive the comment in an indirect way, and it will be more effective.’”

He understands it all. The MKs of the Degel HaTorah party consulting with Rav Gershon

There is a detail that may seem marginal in Rav Gershon’s very expansive life, but it is very characteristic of him: For decades, he has served as the baal tokeia in the yeshivah, and still does. The Chazon Ish would go specially to hear his tekios, and the sounds of his tekios have inspired generations since, even as his strength has waned. The Rosh Yeshivah and gadol also allows free entry to young men who wish to learn how to blow shofar, transmitting the secrets of the trade, the wisdom of tekios.

What he shares with them are the words of Chazal. “The Gemara says that blowing the shofar is a ‘wisdom, not a skill,’ ” he tells them. “When you know how to do it, there is no reason to exert yourself. It doesn’t have to feel heavy and difficult, but the opposite.”

That advice is emblematic of his approach to most areas in chinuch and life. If you know how to do something, it isn’t hard, but pleasant and smooth. If you know why you’re doing it, then it becomes a joy.

And if you know how to get there? Then the path is sweet, filled with growth.

Rav Gershon teaches the way, repeating it again and again.

“Learn Torah and mussar, Torah and mussar,” the Rosh Yeshivah says. Get to know your Creator and His word, and get to know yourself.

It’s not the flashiest piece of advice, and it won’t make headlines, but that’s not who Rav Gershon is. His is not the story of a charismatic, entertaining speaker; a fiery, captivating darshan; a sparkling, witty maggid shiur.

It’s the story of quiet force and insight and staying power, of being able to shape people without fanfare but with steadfastness and consistency. It’s the story of very deep waters beneath a seemingly still surface.

It’s the story of the maggid shiur who, seven decades in, is still saying shiur to a generation.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.