Back to the Motherland

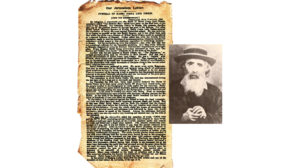

LOST WORLD Belarus. White Russia. We are able to sense the energy still contained in those structures and witness a new generation sprouting on the ruins of a lost world (Photos: Menachem Kalish)

"Posmishka!” the Ukranian policeman barks as we stand at the border crossing threatening to hand us over to the Belarusian authorities a few meters away.

We just shrug. “Posmishka!” he demands again this time with an English translation — “Smile!” It’s late and we’re tired but if the man asks us to smile then smile it is. When he sees our smiling faces he quickly compares them to the pictures in the documents he’s holding. He hands the passports back offhandedly and mutters in Russian “In the picture he is smiling why does he look so sad now?”

“Belarus.” The lettering on the sign glows in the darkness of the night. White Russia. Birthplace of the litvish Torah world. Where gedolei olam walked where chassidic giants held court. The halls of the great yeshivos once brimming with life are now silent but the concrete walls that absorbed so much Torah are still standing. As we stand in the Belarusian night all the stories about Volozhin and Novhardok and Radin suddenly have a real address.

We were told that the locals in Belarus today are an indifferent bunch — they can’t be bothered with such high-strung emotions as anti-Semitism. You can walk the streets in the cities and villages dressed like a yeshivah bochur and no one will bother you. “Just don’t wear your tzitzis out ” we’re advised. “It drives them crazy.” It’s true. Strangers came up to us and asked “Where do those strings come from? From your shirt? Your belt? Explain what they are ” they demand.

In general the Belarusians are known for their unflappable temperament even though — or perhaps because — it’s the last of the countries in the region whose old secret police is still intact even going by its original name KDB. The joke goes that a Russian a Ukranian and a Belarusian each sat in a chair with a nail sticking out of the seat. The Russian immediately jumped up in fury and let out a string of curses. The Ukrainian also got up repeated what the first fellow said and proceeded to pull out the nail with his bare hands then flung it away. The Belarusian sat and feeling the nail poking him let out a cry of surprise and jumped up. He felt the nail with his hands and decided to try sitting again. He was still being poked but continued sitting muttering to himself “Fine this must be the way it‘s supposed to be.”

Perhaps this legendary live-and-let-live attitude played a role in Belarus’s role as the cradle of the yeshivah world.

As the train chugs along we pass many towns and villages. Is this what the Chofetz Chaim and the baalei mussar were referring to in their many parables about traveling on trains — the fool who hid in the freight car when he had a first-class ticket in his hand the misguided soul who moved to the other side of the car instead of taking the train in the opposite direction?

Rabbi Mordechai Reichenstein current chief rabbi of Belarus served as our escort. (For him it was an opportunity to touch base with his communities across the country.) What we saw was both heartbreaking — the glorious legendary yeshivos that were no more — and inspiring as a new generation of Torah Jewry is sprouting right here over the ruins of a lost world. Though in all honesty you don’t really have to travel to Belarus to feel the pulse of the Torah that was learned within these walls— just walk into any yeshivah and open a Gemara and start to learn. That’s what it was about then and that’s what it’s still about now.

Homel: An Illusion?

Not far from the border lies the city of Homel (or Gomel in the local parlance). This large city once boasted a thriving Jewish presence. It was home to many Lubavitcher chassidim and was where the fire of the Novhardok mussar movement burned while in exile between the two world wars. Here the Alter said the shmuessen that comprised his monumental work Madreigas HaAdam. The city’s rav was Rav Avraham Elyashiv known as the Homeler Rav — and the father of Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv.

We arrived at the building of Yeshivas Kehillas Beis Yaakov late at night to a truly beautiful sight. In the corner of the beis medrash sat the current Homeler Rav Rabbi Dovid Kanterowitz surrounded by Reb Yossi — the rosh kahal — and Izza Pasha (Shmuel Dovid) and a few more bochurim animatedly discussing a sugya.

This scene of the citizens of Homel toiling in Torah late at night with their rav — was this really an illusion? And can the local Jews all of them newcomers keep the pace? Rabbi Kanterowitz himself a native-born Belarusian who studied in Yeshivas Chevron in Jerusalem takes a puff of his pipe. “This is where the yeshivish approach in learning came about. Rav Shimon Shkop teaches us a yesod: When there are different levels of talmidim the teacher has to aim for everyone to understand most of what he says and for most to understand everything he says. Still every now and then we provide them with a taste of something on a higher level so that they can see that there is what to aspire to.”

Minsk: On the Street with a Gemara

“Nyama!” the ticket seller tells us in the giant Homel train station. It’s 5:30 a.m. but the station is already teeming with commuters and we came too late to get places on the train. For some of these routes you need to purchase tickets a day in advance. So how should we get to Minsk?

“There‘s the marsharutka ” someone suggests. The marsharutka is a sort of shuttle service with minibuses that run on a route to Minsk making one stop on the way at Bobruisk. We hurry to the central bus station and manage to buy two of the last tickets. (Excerpted from Mishpacha Issue 662 – Special Shavuos Edition 2017)

Oops! We could not locate your form.