Army of One

Malcolm Hoenlein is arguably the most powerful Jewish official in the United States, but he travels without a bodyguard and although he's easily accessible, he conceals more than he reveals.

M

alcolm Hoenlein looks like he might be your neighborhood doctor or accountant: elegant, but not flamboyant, refined rather than in-your-face. His day job is executive vice president of the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations, a cumbersome title.

But in the halls of power and backrooms of political negotiation, he isn’t known by his title, but by his first name. “Malcolm,” they say. “Ask Malcolm,” “Call Malcolm,” say those in the know with a wink, passing around the name like some sort of master key to the Jewish community.

After welcoming me to the functional-but-generic conference room, Mr. Hoenlein speaks, using the diplomat’s gift of saying exactly what he means and no more. He takes a phone call on his old-style flip phone from someone in John Kerry’s office and, once he ends the call, responds to my inquisitive look with words that virtually roll off his tongue. “Can’t talk about that yet, sorry.”

Like the old money changers in Israel, who hung out shingles for furniture stores or falafel shops when their real currency had little to do with the objects on display, Mr. Hoenlein carries a title that tells you little about what he really does.

The group that he represents was established in 1954 at the request of John Foster Dulles, President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s secretary of state. Dulles asked that Jewish leaders formulate their positions together and then present a united voice when they come to the White House, a means of streamlining the lobbying process and saving busy politicians in Washington from talking to dozens of individual groups.

The executive vice chairman of this body carries the combined power of tens of diverse groups — all that influence consolidated into one person. Much of his daily activity involves handling classified information and many of his alliances and relationships remain a secret. A great deal of his time is spent advocating for the interests of Israel, which he does by lobbying, defending, and educating legislators.

The week before our interview he was in Morocco, honored by the king, Mohammed VI, with the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, a military decoration bestowed upon those who have contributed meritorious service to the Moroccan state. The pictures of the robed, red-capped king placing the medal around the neck of the yarmulked Hoenlein almost appear photoshopped, a Jew from Flatbush standing in a sea of djelabas.

Malcolm shrugs when I ask him what he did to deserve the honor. “This and that. I try to help when I can.”

People close to Malcolm say that he largely created the job; his success in advocating for the interests of Israel and the worldwide Jewish community has given him quite the Rolodex. That, along with a remarkable ability to conduct negotiations and stay focused, those same people say, have made him a sought-after advisor and confidant of many foreign leaders.

Orthodox Union executive vice president Rabbi Steven Weil considers Malcolm’s focus his greatest gift. “Sometimes, government leaders have a tendency to talk about everything except the issue you’ve come to discuss — weather, sports, philosophy… Just not the one thing you want to address. Malcolm has this incredible ability to focus on the issue, and when the conversation strays, to refocus and make sure that it stays on the table. I watch him at work and I know why he’s so respected, even somewhat feared, by foreign leaders.”

He’s saved careers. He’s saved governments and individuals from embarrassing headlines.

More than a decade ago, when the Iranian regime imprisoned 13 Jews on charges of spying for Israel, he was the American diplomat who led the charge for their release. Using international connections, Hoenlein mobilized more than 60 countries to unite to pressure Iran. In the end, despite a highly publicized trial and guilty verdict, each of the prisoners was ultimately, if quietly, released.

"I

wish I could take credit, say that I dreamed of helping people, but I can’t. I was led here.”

Hoenlein grew up in Philadelphia, a child of German immigrants. “My parents embodied a message. Their very survival was a mandate to me. I remember reading a quote from Abba Eban: ‘In World War II, Jews had influence in many places but power in none. Influence isn’t enough, you need power to make a difference.’ That picture of the Rabbis’ March on Washington haunts me. Despite their efforts, they could not effect a change. They were turned away at the door to the White House.”

As a child, he attended the local yeshivah day school; when Malcolm reached high school age he joined the relatively new yeshivah in Philadelphia. “Rav Elya Svei and yblcht”a Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky had a strong impact on me. I still see Rav Shmuel at simchahs, and it’s always nice. Besides my old Camp Munk friends, he’s the only one who calls me by my real name, Yitzchok.”

Rav Elya Svei once quipped to a talmid, “When I need to know what’s going on in the world, I read the Times. And when I can’t trust the Times, I call Malcolm.”

Malcolm attended Temple University and then the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned his PhD in international relations. The dynamic young man was active in campus Jewish activities and was soon a rising star in the North American Union of Jewish Students organization. In the post-Vietnam era, the alliance was very liberal, yet they elected an Orthodox president, young Malcolm Hoenlein with his yarmulke.

While working on a master’s thesis on nituchei meisim, autopsies (he was fascinated by the intersection of halachah and law), the student received permission to visit the Agudath Israel archives in New York. Hard at work between files of old legal campaigns, Malcolm barely noticed that the door to the archive room had opened and someone was watching him.

Minutes later, he received a message that Rabbi Moshe Sherer had noticed him and wanted him to come to his office. “When they got my request on university stationery, they thought I wasn’t Jewish, let alone frum. He just wanted to meet me, to encourage me. An instant rapport was formed.”

While still in school, Malcolm married Frieda Shindler and the young couple settled in Philadelphia. “We were short on money, so I taught Hebrew school a few days a week. Later I taught at Penn and was a National Defense Fellow in Middle East studies, and also a Middle East specialist at the Foreign Policy Research Center, based at the university.”

When there was a job opening at the Philadelphia Jewish Council, Malcolm was approached and asked to take charge of several portfolios including Israel, international concerns, and Soviet Jewry. Like the positions that followed, he hadn’t sought the job. The positions came to him. “I was always guided to the next step and believe this is what I am here to do. It imposes a great achrayus, responsibility, to live up to it. It’s why I continue to put in 18-hour days, feeling privileged to do something I’m passionate about. There is no greater reward or responsibility.”

At that time, he made a decision.

“I knew that they would be judging me by my yarmulke. I made a commitment that my work would speak for itself, and the story wouldn’t be about my personal choices but about the job I did. I wanted the best credentials to be able to do what I cared most about.”

He smiles wryly. “Years later, I was approached about a job to lead a very prestigious organization, and I met the board of directors. I said, ‘Listen, I know that there are two things bothering you, my age and my yarmulke. About my age, I can’t do anything, and about my yarmulke, I won’t.’ To my surprise, they invited me back, but I declined.”

The mid-1970s brought changing attitudes on the campaign to free Russian Jewry. For decades, efforts to improve the lot of beleaguered Jews behind the Iron Curtain had largely taken place through quiet diplomacy, the prevailing sentiment being that open displays of Western pressure could only hurt the Jews inside Russia.

Dr. Yaakov Birnbaum’s Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry contributed to changing that perspective. The grassroots organization took to the streets with rallies and demonstrations. Malcolm Hoenlein was asked to come to New York to head the newly organized Conference on Soviet Jewry in Greater New York. In that capacity, he initiated massive Solidarity Sunday talks that drew over 100,000 people to Fifth Avenue and grew each year. He went to discuss the propriety of public gatherings with Rav Moshe Feinstein and other gedolim.

“It’s amazing,” Malcolm reflects. “Rav Moshe was a victim of Soviet oppression and he viewed the regime with justified apprehension. He was astonished that we would take them on, and was worried about their reaction. After a long discussion, the only request made was to make sure not to use tashmishei kedushah, like a tallis or sefer Torah, as symbols, because then they would be seen as the enemy by Russian authorities.”

Coordinating the rallies and events took organizational skill; working with the various activists, however, each with their own agenda, called for diplomatic skills.

Somehow, all of them — those who wanted to yell, those who wanted to threaten, and those who wanted to placate — saw Malcolm as their friend.

The next opportunity to serve came when the newly formed Jewish Community Relations Council of New York invited Malcolm to serve as its executive director. The organization was meant to be a unified voice for various Jewish groups and movements within the city, working for the social and political welfare of the Jewish community. It was a job that put the new director in touch with all segments of the Jewish electorate — and the politicians vying for their votes. Malcolm learned the importance of cultivating relationships at the ground floor and forging relationships with novice politicians.

“He understood, and taught the rest of us, that today’s low-level politicians are tomorrow’s congressmen and governors,” says Brooklyn activist Chaskel Bennett, who considers himself a Hoenlein “talmid.” At the time of the Mavi Marmara Gaza flotilla incident in 2010, when Israel was being roundly condemned in the world press and halls of power, Malcolm called young Chaskel Bennett. Aware that Bennett had been working on developing a relationship between a relatively fresh politician and the Jewish community, Malcolm urged Chaskel to explain Israel’s position to his political friend. “Israel needs every friend it can get. You’ve been working on this for quite some time, now you need to cash in and get the politician on board.”

Bennett recalls being amazed at how Malcolm, with relationships dotting the globe, didn’t lose sight of a relatively unimportant connection, remembering it and putting it to work for Eretz Yisrael.

When the young Hoenlein family moved to New York in 1971, the man who would become the toast of secular Jewish activists planted himself firmly in the heart of the frum enclave of Flatbush, davening at the Vyelipoler shul of Rav Yosef Frankel and sending his children to local yeshivos.

“I understood that the role I would play would largely be on a stage beyond the Orthodox community, but what I did wouldn’t affect who I was.”

A Flatbush neighbor recalls Malcolm’s taking the phone one Friday in 1989, just at the zeman. Rabbi Herman Neuberger was on the phone.

With Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega overthrown, his forces had surrounded the shul in Panama City and the Jews were in danger. Malcolm got to work, arranging for United States Marines to protect the shul until the military operation was over; then he straightened his tie and went off to Rav Frankel’s shul in time for kabbalas Shabbos.

The connection with the Vyelipoler shul was an old one; Malcolm’s in-laws, the Shindlers, davened by the Rebbe’s father in Crown Heights. And even as Malcolm accomplished great things on the world stage, he remained the same private citizen, a Jew at prayer, when in shul.

Prominent attorney Jacob I. Friedman davens at the same shul, and remarks that no one would guess Malcolm’s international stature from observing his unassuming manner.

“Nothing seems to make him prouder than bringing an einekel to shul. When I see him in the media, I think to myself, ‘Wow, this is our quiet Malcolm.’ ”

“Malcolm advocates not only for the physical survival of Klal Yisrael,” reflects another neighbor and shul-mate, Rabbi Menachem Lubinsky, “but for its very neshamah. But even as he doesn’t sleep at night worrying about Klal Yisrael, he is still very much the individual, a loyal friend, a great father and husband, and a wonderful grandfather.”

A humorous memory from that time: Malcolm Hoenlein was being looked to as a power broker on the wider stage, and his friendship was sought in the highest corridors of power. One evening, he received a phone call at home. It was the president of United States, Jimmy Carter. Once he confirmed that the caller was indeed the president, as claimed, Malcolm went to another room and spoke with the leader of the free world. Little Chanoch Hoenlein, just eight years old, followed his father and the president heard the child’s chatter. “Who’s in the background?” he asked. Mr. Hoenlein explained that it was his son, and Carter asked to speak with him.

He asked the child which school he attended. “Torah Vodaath,” was the reply.

“How old are you?”

“Eight,” Chanoch answered.

“Well, I hope you’ll come visit us in the White House one day and play with my daughter Amy, she’s about your age.”

“I go to yeshivah,” came the prompt response. “We don’t play with girls.”

The White House shared the charming story with the press and it was widely reported at the time.

It’s a cute anecdote, but it’s also revealing: Authentic Judaism wasn’t something that the Hoenleins apologized for.

“Honestly, I never found that my demands, be it the yarmulke, kosher food, or having to leave early on Friday, were greeted with anything other than automatic respect. But it is not something I take for granted. You have to earn respect, not demand it.”

Mr. Hoenlein pauses. “It’s actually sad that much of the secular world has less respect for a yarmulke than they once did. Look at the headlines and see how they write about us. We’ve taken a step backward.”

A

great part of Malcolm’s work at the JCRC involved creating an umbrella over various Jewish organizations that had common interests, investing each with the strength of combined numbers of smaller groups from Bensonhurst to the Bronx.

“It surprised me how little the most powerful Jews in the city, people who considered themselves advocates of Jews and Israel, knew about genuine Orthodox Jews. One of my pet projects was taking some of them to see religious Jewry up close. The distance from the Upper East Side to Boro Park may not be great, but most of the secular Jewish Manhattanites I took on my ‘tour’ had never seen that part of Brooklyn. It was a new world for them.”

He once led a delegation comprised of Manhattan’s “first families,” Tisches and Tishmans and other leaders of the JCRC, to Boro Park.

“I took them to meet the late Bobover Rebbe, Reb Shloime ztz”l. They were amazed. They had never really met chassidic Jews and here they were, in the hub of chassidic Judaism, being welcomed by this radiant man, a grand rabbi no less. He sat with them for a long time, exuding warmth and respect. He told them his story, even showed them pictures of himself dressed as a non-Jew while helping Jews escape the Nazis, and answered all their questions.

“One of the most prominent participants in that meeting was so impressed that he followed up with a private meeting with the Rebbe, so he could ask all his questions. I felt that it was an accomplishment.”

On a subsequent meeting with the Satmar Rebbe, Rav Yoel Teitelbaum ztz”l, one of the men asked the Rebbe for his feelings about a recent attack on a Conservative temple, in which Orthodox zealots had covered the building with graffiti. The Rebbe didn’t hesitate in condemning the use of such tactics and said they could quote him in the press. “It was a remarkable exchange and dealt with very controversial issues. The Rebbe addressed each with eloquence and understanding.”

Malcolm’s success at the JCRC was noted and in 1986, he was offered the top executive position at the UJA-Federation of New York. On the same day, the executive of the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations died suddenly.

After a national search and swift interview process, the position was offered to Malcolm Hoenlein.

He remembers the decision. “The UJA-Federation was a huge organization, with a big agenda and a big staff, and the President’s Conference was a small office with a much smaller salary. My son heard me mulling it over with my wife and he said, ‘Abba, you won’t be happy unless you’re making a difference.’ ”

Malcolm Hoenlein took the Presidents Conference post and went out and made a difference, lifting the understaffed organization to the heights of international relevance. Its positions on Israel and general Jewish issues became the guidepost that other organizations followed. Malcolm, carrying the influence of the organizations and leaders behind him, emerged as a “go-to guy” for politicians and diplomats eager to address the wider Jewish community; he, in turn, became a spokesman to communicate the community’s concerns at all levels of power.

The tiny staff, he tells me, is the way he likes it.

“I don’t have much tolerance for bureaucracy. We have just a bare-bones staff, a lean, mean machine that gets the job done and works long hours. I don’t have a public relations person. I don’t like giving interviews much — too often I get taken out of context. I’m a disappointing interview anyhow,” he says with a laugh. “I don’t share secrets and I don’t leak.”

He has no driver. “I had one for a few weeks at the insistence of a concerned major donor, but it was too invasive. I know how to drive to Brooklyn by myself.”

He also has no security guard. “There were times when they insisted I be accompanied by a guard, but I let him go. If terrorists want to get someone and it’s bashert, they’ll get him. If it’s not, they w

W

ell-spoken and courteous as he is, it’s clear that Mr. Hoenlein has the proverbial “iron fist in a velvet glove,” the steadfastness and tenacity to get the job done. I get a sense of this side of him as he recalls a trip he took, along with his wife, in 1970.

There was a Jew facing trial in Kishinev, Moldavia — then part of the Soviet Union — and Malcolm and his wife flew over there to lend their support. They were arrested on charges of being “Zionist” and “CIA” agents. During the interrogation in a special room at the hotel, conducted by a high-ranking official, Malcolm went to battle.

“Bring me proof of the charges,” he demanded.

In the security of his Manhattan office, he describes how he argued with them. And all these years later, his eyes still flash fire. I see his fighting pose, shoulders square, chin defiantly turned up.

“They took my tefillin from me and after asking what they were, they challenged, ‘How’s your G-d going to save you now?’ I looked right back at them and said, ‘Oh, don’t worry, He’ll find a way.’ ”

He found a way and the Hoenleins were released and sent on a 55-hour return trip. Malcolm never forgot the experience. “Being arrested had a big impact on me. I was free, but many others were not.”

The Soviets didn’t forget, either. Years later, Senator Al D’Amato was planning a trip to the USSR and he invited Malcolm to be part of his congressional delegation.

“The Russians saw my name and rejected the whole thing. They said, ‘You’re not coming and he’s not coming.’ ” The same happened when then secretary of state George Shultz put Malcolm on the list for a similar delegation.

Another glimpse at his tougher side: In 1994, Malcolm was in the lobby of a Casablanca hotel and saw Yasser Arafat approaching. The PLO leader seemed intent on a pleasant exchange, so Hoenlein changed paths, walking around the elevators and effectively snubbing Arafat.

“He was so offended, he sent a message to George Shultz to complain. Later, he also complained to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. I told the prime minister that I couldn’t bring myself to shake that hand, but remarked that if it would benefit Israel, I would meet him. He said to me, ‘Don’t do it. He wants it badly. Wait. Let him do something first.’ He then told me a great deal about his feelings and interactions with Arafat. At the White House ceremony for the peace-agreement signing, when both Rabin and Arafat were present, I shook hands with Rabin on the security line. He pulled me close and whispered, ‘Not yet.’ ”

The ability to walk the fine line between subtle negotiation and imposing force is a Hoenlein hallmark. Rabbi Steven Weil recalls sitting at the White House, conferring with the current president, along with a group of Jewish leaders. “There’s a tendency, when you’re sitting there, to sugarcoat things, to become intimidated by the place and position and simply nod along. Malcolm is able to address the president respectfully, but directly, unafraid to argue a point — courteous and polite, but no pushover. I found that impressive.”

A

s much diplomacy as it takes to earn respect and concessions from hostile governments, it takes equal subtlety to work each day in an office that aims to speak for so many different types of Jews. How does he do it?

“I often joke that that our success in having an umbrella organization for so many different viewpoints is that I give them all a common enemy — me.

“On a serious level, our success is that we leave halachah to rabbanim, because by definition, halachic issues can’t be decided by consensus. In the actual process of how to help, though, then we can at times step in.”

Mr. Hoenlein was one of the first activists to urge the Orthodox community to realize its own power. “I got letters from Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Moshe Feinstein, and the Debreciner Rav confirming the halachic mandate to register to vote. The candidates know exactly how many people vote in each community and they react accordingly. If we want to be taken seriously, we have to participate in the process seriously.”

He was able to educate the community in other ways as well. Conventional wisdom was that Jews vote Democratic and that wouldn’t change. Malcolm felt that it was a mistake for the community to be in a position of being dismissed by one party and taken for granted by another. Today, things have changed. The community has taken to voting for the individual and not the party label. Malcolm remembers the Giuliani election in 1994 as a turning point in that regard, when the Orthodox community voted overwhelmingly Republican.

Within the frum community, Malcolm has had many good friends who have guided him along the way, and he is gracious in deflecting the credit for many of his accomplishments.

“Starting with my parents. My father was a proud, smart, strong man, deeply committed to Yiddishkeit. My mother was a kindergarten teacher her whole life and it wasn’t until her shivah that I learned how many people she had made frum just by the impact she had on them in their youth. My parents came through the gehinnom of the Holocaust, losing their parents and relatives, arriving here with nothing. Yet they built a frum Jewish home. My father would be fired from his job on Fridays because he would not work, but they were never bitter about it.”

He considers Rabbi Moshe Sherer and Rabbi Herman Neuberger mentors. “Both these men taught me that to be effective, you have to have a thorough grasp of the issues, be well-informed to make a difference. They enjoyed much wide respect, trust, and through that, influence. Early on, Rabbi Sherer introduced me to Senator Javits and said, ‘He’s one of my guys.’ I wore that proudly.”

He looks at me with a soft smile. “And your grandfather. Rav Chaskel Besser had this ability to walk into a room and win people over with a smile. I would often bring him to meet the secular Jews on the board of the JCRC when we had a problem, knowing they would connect with him. I had the zechus to travel in Eastern Europe with him and was fascinated. He knew the history of every stone. He was a great influence on me and could even offer criticism in a positive way. I’m still moved by the request he left in his tzava’ah that I speak at his levayah. Unfortunately, I was in Israel at the time.”

Mr. Hoenlein also considered the Lubavitcher Rebbe a spiritual guide.

“It was before my son’s wedding and I wanted to get a brachah for him and his kallah from the Rebbe. This was already late in the Rebbe’s life. We drove to Crown Heights, and there was a long line waiting to receive the dollars the Rebbe distributed. Someone saw us approaching and ushered us in through the front door, unannounced. When I approached, his secretary, Rabbi Groner, said to the Rebbe, ‘This is…’ but the Rebbe cut him off and said, ‘I know exactly who it is.’ ”

The Rebbe held Mr. Hoenlein’s hand and smiled broadly. The Rebbe began to discuss different issues in which Mr. Hoenlein was involved, displaying an in-depth knowledge of each topic.

Then Mr. Hoenlein requested a brachah for his father, who was hospitalized. The Rebbe said, “Your father should continue to have nachas from all the good works you do.”

The conversation continued and again, Mr. Hoenlein mentioned his father for a refuah sheleimah. The Rebbe gave the same answer. “He should continue to have nachas from all the good work you do.”

The Rebbe gave a brachah to the chassan and kallah and spoke to them. Malcolm tried one last time. The Rebbe let go of his hand, stopped smiling, and said. “Your father should continue to have nachas from all the good work you do.”

“I drove back to Flatbush, got my tallis and tefillin, and went straight to the hospital in Philadelphia. I was with my father and had a chance to say goodbye. He was niftar that night. The Rebbe gave me that opportunity to part from him.”

Presently, Mr. Hoenlein considers both Rav Aharon Yehudah Leib Steinman and the Belzer Rebbe people he can turn to. “I try to visit Rav Steinman, who has so much wisdom and humility, whenever I can. He is very direct and speaks ‘to the inyan.’ I find that the Belzer Rebbe is very smart. He has a global sense, a real understanding of the issues and genuine concern for Klal Yisrael. Both leaders are so warm, perceptive, and, surprisingly, have a unique sense of humor. I also met several times with the Gerrer Rebbe, who likewise has a clear sense of responsibility for others, a deep commitment to solving the problems facing his community and Klal Yisrael.”

In recent months, with the Israeli government and the yeshivah world seemingly at war, Malcolm has been looked to as a lone figure capable of bridging the gap. He has been less than thrilled with the perceived role into which he’s been thrust; he’s far more comfortable doing his thing between monarchs and dictators than running between gedolim and politicians.

Yet, with his characteristic stateliness, he’s dedicated himself to this as well, meeting rebbes, roshei yeshivah, and the Israeli prime minister, and attempting to bring the two sides to an understanding. “There is no question that there are serious issues that divide them, but equally certain is that the incitement by the media has made this a lot worse and the accusations and lack of respect on both sides hasn’t helped. I think that with respectful dialogue we can satisfy both sides here.”

Our photographer, Meir, is eager to walk into the inner offices, to get out of the conference room and see where Malcolm works. Reluctant as he is, our host eventually acquiesces; he can best politicians and out-negotiate diplomats, but he’s no match for our Israeli photographer.

His small office features pictures of him with most of the relevant politicians in recent history. There is a photo of Israeli fighter jets flying low over the gate into Auschwitz, signed by Ehud Olmert. “I complimented the picture hanging in his office. When I arrived back in America, there was a package with a copy waiting for me.”

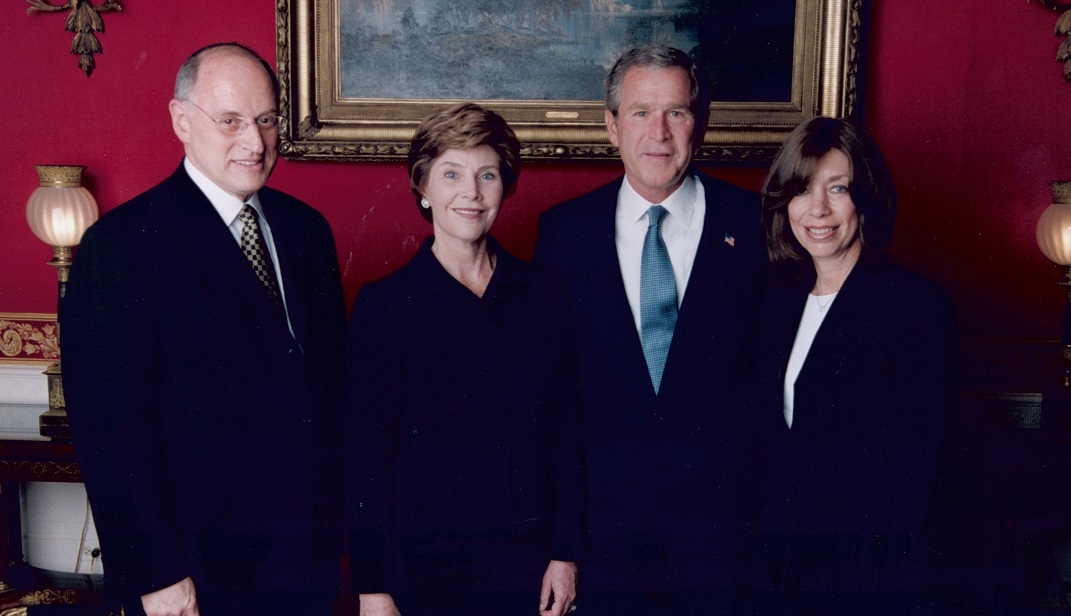

There are pictures of Mr. Hoenlein with several former US presidents. Are any of them personal favorites?

“I don’t like when people talk about which presidents were anti-Israel and which weren’t. I think they were by and large committed to Israel. The senior President Bush had tears in his eyes when apologizing for a remark he made, declaring himself ‘one lonely man against 1,000 lobbyists’ [Jewish leaders who had come to press for loan guarantees for Israel]. He insisted that he’d thought differently throughout his life and that the comment didn’t reflect his philosophy. He was sincere and repeated the apology to a group of Conference leaders a short while later.

“I arranged a ceremony at the White House to declare National Jewish Heritage week. It coincided with the Bitburg controversy [in which President Ronald Reagan went to visit a German military cemetery even though there were SS soldiers buried there] and Eli Wiesel spoke. He urged the president not to go, saying, ‘Mr. President, that place is not your place.’

“Reagan called me into his office before the ceremony and explained his frustration at the situation. Then he told me how, as a US soldier in World War II, he was assigned to a film unit, and before his discharge he took a film of the camps, though he knew it wasn’t legal. He told me that he felt that people would deny the magnitude of Nazi crimes and he wanted his children and grandchildren to be able to give testimony to the Holocaust.”

Many activists and politicians have transferred activism into personality cults. How does Mr. Hoenlein keep his bearings, keep himself out of the picture?

He shrugs off the question. “I don’t have many special talents. I can’t sing or dance or draw. I have the skills that Hashem gave me, an ability to work with other people, to analyze and foresee issues and work through them, and an ability to communicate. Why should that make me arrogant?”

Also, he adds, he gets reminders that things happen that have nothing to do with him. And of course, there’s a story.

“We had a meeting with [national security advisor] Brent Scowcroft about helping Ethiopian Jews. Scowcroft wasn’t giving in to us, and we were deadlocked when suddenly, he got a phone call from President George Bush, the senior, to come to his office. As he left, I asked General Scowcroft to ask the president if he would grant permission for the mission that weekend during the 48-hour window we had. If he refused, I remarked, we would see pictures of dead Ethiopian Jews, like those of Iraqi Kurds who had been murdered, on the front page of the New York Times.”

Scowcroft was caught off guard and he repeated Malcolm’s words to the president.

A few minutes later, Scowcroft came back to the meeting and said, “It’s a go. The president okayed it.”

“Later, Senator Rudy Boschwitz asked me, ‘What was that? How did you think to do that?’

“And the honest answer was, I had no idea. I heard the words the same time that the others did.

“So it’s hard to hold yourself high when you feel that things are happening with and to you, rather than because of you.”

I

f Mr. Hoenlein has any regrets, it’s that he didn’t have much free time when his children were young. He has a busy schedule, even today. In addition to the meetings and travel, he needs time simply to stay abreast of developments in the world. Most nights, he does his reading and paperwork, prepares for his three weekly radio shows and countless speeches, and enjoys the quiet time from 11 to 3 a.m.

“My anchor time is Shabbos, especially with my children and grandchildren. My other moments of serenity come during my learning sessions with Rabbi Uriel Reich of Lakewood, a remarkable talmid chacham, articulate with a wide breadth of knowledge, and a tolerance for my schedule.

“But Hashem paid me back. He gave me a devoted, selfless wife who managed to raise truly wonderful children, with His help. I am grateful for that. When I look at my grandchildren, all bnei and bnos yeshivah, I see the greatest reward Hashem can accord.”

As he escorts me down the maze of hallways leading from his office, I pepper him with some final questions.

Does he see the frum community spawning more Malcolm Hoenleins?

“Sure. If you look at the leadership situation in the general world and look at our community, you’ll see that we’re doing pretty well. We have plenty of young, dedicated askanim who are selfless and talented.”

Once a year, on a winter Friday night, he gives a talk about the world political situation at the Young Israel of Midwood, to a standing-room-only crowd.

He stops walking and looks at me. “One thing we need, though, is achdus. Learn Tanach. Klal Yisrael was never helped if they didn’t have unity. It’s the one prerequisite for every neis, miracle, and great achievement. If we hope to achieve and fight the threats, we need to work together.”

It can sound like a sound bite, like a tired truism: Let’s work together.

From anyone except Malcolm Hoenlein, talmid of Philadelphia, alumnus of Temple University and Penn, champion of Jews in all sorts of hostile environments and settings, confidant of presidents, effective ally of Israel, and cherished intimate to gedolei Yisrael.

He knows what it means to work with others.

And he’s seen his share of miracles.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 505)

Oops! We could not locate your form.