Afula Gold Rush

When Rabbi Menachem Gold moved his young family from Jerusalem to Afula in Israel’s north, he was sure of only one thing: a calling to help

(Photos: Koter Rubi, Elchonon Kotler)

H

eat radiates from the street where a line of taxis waits outside the central bus station in Afula, a city of 50,000 in Israel’s north, at the center of Emek Yizre’el, the Jezreel Valley. One driver, a tall, courtly, middle-aged Sephardi man with a trim mustache, opens the door of his white Mercedes cab. The gust of air-conditioning offers blessed relief.

He evinces a flicker of recognition when he is given the address, on Rechov Tzukit. He cocks his head and turns to his passengers.

“LaRav Gold, atem rotzim? [To Rav Gold, you want?]”

The ride affords a street-level view of a city on the move, with new construction abounding. Row upon row of new apartment buildings march across the valley floor. The road winds up an embankment, offering stunning vistas of Mount Tavor to the north.

The cab arrives in the neighborhood called Givat Hamoreh, “the Hill of the Teacher,” and pulls up to a humble public school. Standing out front is Rabbi Menachem Gold, already beaming as his guests disembark from the taxi. The driver approaches for a greeting and a blessing, which Rabbi Gold delivers warmly in Hebrew with a charming American brogue.

After the cab departs, Rabbi Gold guides his guests on a tour of this elementary school, called Marom, which he founded in 1997. He bounds up the stairs with an enthusiasm matching that of the young children scampering about.

“This is a very special place, with very strict admissions requirements,” he explains, with a mischievous glint in his eye. “To get in here, your family must be mechallel Shabbos.”

This school is the cornerstone of Rabbi Gold’s efforts to completely transform the spiritual landscape of this city. Afula became a destination for Jewish immigrants from North Africa in the years after Israel’s War of Independence. Later, with the collapse of Communism, another wave came from the former Soviet Union. Many were only tenuously connected to Torah observance when they arrived, and the ethos of the secular state only reinforced the trend over time. Rabbi Gold started the Marom school with the intent of introducing the tenets of Yiddishkeit to these secularized families through their grade-school-age children.

Marom follows the Israeli mamlachti-dati model, a religious public school operating on government funds but with an Orthodox bent. The classes and the faculty are coed, but the instruction is otherwise geared to instill a strong sense of Jewish spiritual identity.

When the children bring home their Shabbos- and Yom Tov–themed projects, along with divrei Torah on the weekly parshah, it inevitably foments religious discussion with the parents — which often leads the family on a path toward greater observance.

The revolution has been so successful that it spawned a second generation; the first children who passed through Marom’s doors have grown up, married, and now have children of their own. Some have even chosen to pursue kollel studies full time. Rabbi Gold has had to open new institutions to keep pace with the growth — and increasingly chareidi direction — of the movement he has sparked.

With the addition of a cheder, a Bais Yaakov, yeshivos, and a local kollel (among other institutions), Afula is suddenly on the radar for young Israeli chareidi families on the lookout for affordable housing in communities with a Torah infrastructure. (The average price of a three-room apartment in the “black” neighborhoods of Givat Hamoreh and Afula Illit is around NIS 450,000 — which these days no longer even buys a machsan, a converted storage room, in Jerusalem.)

The transformation that Rabbi Gold set in motion has gathered a momentum of its own. As his movement has flowered and staff has joined his ranks, he has rolled all his various initiatives under one umbrella nonprofit organization called Mashma’ut, so named for the meaning he hopes to bring to the lives of people seeking spiritual uplift. Meanwhile he himself shows no sign of slowing down, no diminution in motivation.

“There’s a powerful force for Torah in this country, we just need to unleash it,” he declares with a flourish. “One hundred and fifty years ago the Reform movement started. Now Hashem has swung the pendulum the opposite way. Jews are hungry and thirsty. If we can show them the beauty of Torah, we can change the direction of the country.”

When Rabbi Gold first moved his young family to Afula in 1996, the city was a spiritual wilderness, devoid of any religious support system. He and his wife, Dina, had to send the children to schools in other nearby yishuvim. (Their seven children now range in age between 29 and 12, and three are married.)

When Rabbi Gold introduced himself to his new neighbors by offering to give their children bar mitzvah lessons, check their mezuzahs, and give Torah shiurim, he was only following in the footsteps of his well-known father, Rabbi Sholom Gold of Williamsburg, formerly rav of the Young Israel of West Hempstead, Long Island, and now rav of Kehillat Zichron Yosef in Har Nof, Jerusalem. “I come by it honestly,” Rabbi Menachem says.

Rabbi Sholom Gold, now 83, is a product of Ner Israel in Baltimore, and in 1959 he was sent at the age of 24 by his rosh yeshivah, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, to Toronto with the goal of opening a branch of the yeshivah there. The Toronto kehillah of those years was not yet familiar with the concept of yeshivah learning; most Orthodox parents were focused on getting their sons into prestigious universities. Persuading these parents to enroll their prodigies in a traditional Lithuanian-style yeshivah meant knocking on doors and hashing it out with them face-to-face.

The elder Rabbi Gold met with success, but that doesn’t mean he was happy to hear about his son Menachem’s decision to attempt something along the same lines in Afula.

“I was sent by my rosh yeshivah to Toronto, but there were balabatim waiting for me there,” he says. “All those who were sent out from Lakewood or Chofetz Chaim or Ner Israel, everybody went somewhere where there was somebody waiting to greet them. Here, there was nobody. Menachem was just packing up and saying, ‘I’m going to do something in Afula.’ We were very concerned — who does something of this sort?”

Even today, Rabbi Menachem finds it challenging to articulate exactly what motivated him to move to Afula. He learned in Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim in New York, then in Ateret Yisrael in Bayit Vegan under Rav Boruch Mordechai Ezrachi, and then the Mir. (He maintains a close connection to Rav Ezrachi to this day.) He got semichah yoreh yoreh from Rav Yitzchak Kolitz, chief rabbi of Jerusalem, and from the Rabbanut.

As a bochur, he went to Kiryat Shemonah, near the border with Lebanon, to engage in kiruv activities with a friend, and fell in love with the region. He decided he would one day return, and even told his young wife of this plan after their wedding, when he started learning in kollel in Jerusalem.

“I told my wife not to get too comfortable in Yerushalayim because someday we’re going to be moving up north,” he reminisces. “She didn’t take me too seriously… and after about nine years in kollel, I got this thing in my head, I can’t explain it. I don’t want to sound crazy, but something told me it’s time to go.”

“It was really, extremely difficult to even think about coming here,” says Rebbetzin Dina Gold now. “He had wanted to go all the way north, up to the border with Lebanon. We ended up compromising on Afula, which is the southernmost part of the north.”

Reb Menachem explained his idea to his rosh kollel and asked for some time off to scout out cities in Israel’s north. His itinerary took him to Acco, Atlit, Tirat Carmel, Yokneam, Nesher, Nahariya, Kfar Yonah, Hadera… and then, on Tu B’Shevat, to Afula.

“Something about it just appealed to me,” he says now. “If you go to a city that’s too large, you can get lost in the crowd. If it’s too small, then you can’t really do much. You need a midsized city. Afula was about 40,000 people at the time, mostly Sephardim, and I found that I was received very well. I said, this is the place.”

Breaking the news to his wife was not an easy task. Mrs. Gold was then working for Bituach Leumi, Israel’s social insurance program, in computers, and earning a healthy high-tech salary. She would be giving that up for her husband’s venture.

“She grew up in Sanhedria Murchevet, she’s from America originally, a nice frum girl tied to her family,” Rabbi Gold says. “Kol kevudah bas melech penimah, she fits that bill perfectly. When I dropped the bombshell, if you think Hiroshima and Nagasaki wreaked havoc…”

“It hit me like a lightning bolt when he told me,” Mrs. Gold concurs. “To leave our familiar surroundings, all our friends, a good job, to go to a place where we really knew no one… And there were very, very few really frum people in Afula when we moved here.”

Mrs. Gold currently works as an English teacher in Ulpanit Teveria, a high school where many of the girls are on the religious fringe, and contributes wherever she can to her husband’s cause. Rabbi Gold says that his wife’s round-the-clock guidance and advice has been indispensable to all his efforts.

A

lthough in hindsight it seems the move was justified, Rabbi Gold doesn’t minimize the enormity of what he was asking of his family at the time. “This was really difficult. But I felt I had no bechirah. Look, I don’t want to sound like a meshugeneh, but there was something that was pushing me.”

His father, Rav Sholom, also weighed in on the topic. Rabbi Menachem recalls being taken aside and asked how he was going to make a living in Afula. He replied to his father, “Money’s going to stop us from doing this great thing, bringing Yidden to Torah? We’re going to let a small technicality like that get in the way?”

His father dropped the subject. Then, some weeks later, Reb Menachem was at his parents’ home in Har Nof when a knock came at the door. Reb Menachem recalls answering the door and finding an elderly man there, who asked for “Rrrabbi Gold,” with a thick, European uvular fricative R.

“I knew he didn’t mean me,” says the younger Rabbi Gold.

He brought the man in to his father, and then left to return to his home in Beitar. Rabbi Sholom Gold sat with the man, who was 90 years old and named Moshe Ber. He said he remembered Rav Sholom from Williamsburg, and explained that he and his wife were Holocaust survivors who never had children, and his wife had been niftar two weeks before. She had accumulated savings over the course of her life, and stipulated that after her passing the money should be donated to a worthy cause: kiruv for Jewish children distant from Torah, somewhere in Eretz Yisrael.

Rav Sholom took all this in with great surprise, but collected himself and opened up a map of Eretz Yisrael and pointed to Afula. As he recounts in his book Touching History: From Williamsburg to Jerusalem (Gefen Publishing, 2015), he told Reb Moshe Ber, “My son Menachem is moving here with his family. He is going to start a school for precious Jewish children in a city where Torah is pretty much unknown.”

The man then took out his checkbook, wrote out a check, and handed it to Rav Sholom. It was for $50,000.

“It seems that my son’s bitachon was far more effective than my rational parental doubt,” wrote Rav Sholom.

That seed money funded Reb Menachem’s first year in Afula, allowing him to establish what he calls a “beachhead.”

“The first year that I was here, I worked on my own,” he says now. “I had nobody with me. I would tuck my children into bed at night, and then I would go out. I would take a row of houses, and I would start knocking on doors, with my heavy American accent. ‘I’m new here in town. We teach bar mitzvah lessons, we check mezuzahs, we have afternoon activities for kids.’ People would say, ‘Wow, an American in Afula! What are you doing here?’ It was something really interesting for them.”

Rabbi Gold has found the winning formula for penetrating the notoriously prickly exterior of the sabra. His demeanor is at once disarming and engaging, and he projects an air of earnestness and enthusiasm that immediately endears him to native Israelis in Afula.

“There’s something about the American personality,” he says. “I think we bring the best of all worlds. We can use it for good things, so why not?”

A

t the end of that first year he had compiled a list of 300 to 400 families with whom he had built a relationship. Since his staff then consisted basically of himself, his organizational reach was pretty limited, so he had to think creatively to keep those families engaged.

“I’m not Amnon Yitzchak, that I can speak to the guys for five minutes, and poof!” he says, referring to the Mizrachi kiruv rabbi who rose to prominence in Israel in the 1990s. “So on my own I would take a whole group of families, subsidize them, and send them to Arachim seminars.”

The seminar had the desired effect on one Afula family, but their move toward greater observance was stymied by a lack of appropriate educational facilities for their daughter, only in sixth grade. Rabbi Gold checked around and found a religious public school run by Chabad on a nearby yishuv, and was able to get the girl an interview with the principal. She got in, and eventually continued on to a girls’ school in Migdal Ha’Emek run by Rav Yitzchak Dovid Grossman. Rabbi Gold still saw the father from time to time but eventually lost contact.

Then, years later, after Rabbi Gold had managed to open a chareidi Talmud Torah in Afula, he was walking his youngest son to the gan there. When they reached the cheder, he encountered a young, modestly attired religious woman, with her own son. When she saw him, she said, “Harav Gold, mah shlomcha? [How are you?]”

He begged her pardon and said he didn’t recognize her.

“Harav Gold, atah lo zocher oti? Ani Shikma! [You don’t remember me? I’m Shikma!]” She was the one he had helped get into the Chabad school. She then indicated her son, and mentioned her other children and her kollel avreich husband, and said that all her blessings were due to Rav Gold.

“All I did was bring her for an interview with the principal at the frum school, and that was it,” he says with evident wonder.

Rabbi Gold likens it to a gemara in Bava Metzia (85a), in which Rabi Yehudah Hanasi locates the orphaned son of Rabi Elazar ben Shimon and arranges for him to attend a cheder. When the orphan shows up years later in Rabi Yehudah Hanasi’s yeshivah and identifies himself, Rebbi quotes a pasuk in Mishlei (11:30), “Pri tzaddik eitz chayim, v’lokeiach nefashos chacham. [The fruit of the righteous is a tree of life, and he who wins souls is wise.]” The Maharsha asks why Rebbi quotes a pasuk that uses the plural, nefashos, when he had really only saved one soul, that of the orphan.

The Maharsha answers: When you bring one Jew back to Torah, you bring his descendants along also.

A

fter that first year, Rabbi Gold became aware of two funding opportunities that would eventually pay perpetual dividends. The Wolfson Foundation announced it was seeking applicants to open community kollels in Israel’s north, and Rav Aharon Leib Steinman ztz”l and the Gerrer Rebbe shlita declared a fundraising drive for a network of Chinuch Atzmai schools for children from nonreligious homes. Rabbi Gold immediately jumped on both offers.

“I’m a very nice, outgoing fellow, but to turn over a city, you need an army,” he says. “The Wolfson organization turned to me, Johnny-on-the-spot, and we opened up a kollel.”

For the school, which would eventually become Marom, Rabbi Gold managed to round up four first-graders and three second-graders from his list of families. Then Hashgachah pratis ordained that Afula would undergo Israel’s longest public school strike in history in 1997. For six weeks, every other school in town was closed, and Rabbi Gold’s was the only one open.

“Parents were going crazy,” he says. “They’d come to me saying, ‘Gold, just take my kid already!’ We managed to get a lot of kids out of public school simply because their parents couldn’t handle them at home.”

By the end of that school year, Marom had 40 children enrolled and was operating a nursery and a preschool. With that baseline, it was able to add a new class each year. There are now two kindergartens affiliated with Marom in the neighborhood that serve as feeders to the school. Over time, the school garnered a reputation for academic excellence — such that Rabbi Gold no longer needs to knock on doors to round up students. Families are pulling their children out of the public schools and jostling to get them into Marom. Rabbi Gold gives full credit to Mrs. Hadassah Rotenberg, Marom’s menahelet.

“This principal is fantastic,” he says. “I just try to keep out of the way.”

Mrs. Rotenberg is quick to return the compliment. “With all the things he’s busy with, Rabbi Gold finds the time to help us a lot here in the school,” she says. He arranges for yungeleit from the kollel to teach classes about aspects of Yiddishkeit, like Yamim Tovim, Shabbos, and kashrus. She recounts one story involving a boy from a home very distant from observance and the impact that an avreich’s lesson on Pesach had on the family.

“This child, seven years old, was from a family that ate bread, pizza, and pasta all through Pesach,” she says. “The avreich talked about how we don’t eat any chometz, and this child told his mother he would not eat any chometz during Pesach, and she listened to him — even providing him separate plates and utensils. All these little things add up.”

Whereas previously the majority of Marom students came from one-parent or dysfunctional families, now they are the minority. Russian immigrant families in particular are now drawn to the school, and they demand very high academic standards.

“They want English and piano,” Rabbi Gold says, smiling. “By them, English is yehareg v’al yaavor. They’re not coming here for the Yiddishkeit, they’re coming for the academics. So we have to be better than the public school. That’s the market segment we’re after.”

The only limitations facing Marom right now are the size of the building (“If we can move to a regulation-size building, we’ll be able to open the floodgates to the community,” Rabbi Gold says) and the lack of suitable options after grade six.

“We need a junior high school and a high school,” Rabbi Gold says. “After grade six we have to send them to places where they don’t really find themselves. They’re nisht ahin, nisht aher. They’re not really in the frum world, but they baruch Hashem got a taste of davening and Chumash and all that. We have to get them from the cradle to the chuppah! It’s absolutely crucial, we must have a continuation of the school. Their parents have been begging us for years, but I don’t have the facilities.”

R

abbi Gold’s kollel — known as Kollel Mashma’ut — also took root and began netting big returns on the Wolfson Foundation’s investment. The Wolfson funding conditions required the avreichim to work two and a half hours every night on behalf of their local community. They joined Rabbi Gold on his nightly neighborhood jaunts, knocking on doors, trying to sign up unaffiliated families for Wolfson seminars. The pressure to fill the seminar quotas was formidable; avreichim got very nervous when a hotel was only half-booked one week before a seminar. But again, Hashgachah pratis worked in Rabbi Gold’s favor, in the form of a sudden societal awakening.

“There was a period of five years, around the turn of the millennium, when there was an earthquake in this country,” Rabbi Gold says, describing an era when suddenly the tenor of Israeli society seemed tuned in on teshuvah. “There was Amnon Yitzchak and seminars put on by kiruv organizations like Arachim and Lev L’achim… The place was rocking. And we were riding that wave.”

His kollel yungeleit recruits were also energized, and more than up to the task.

“These guys were incredible, they were pioneers in their blood,” Rabbi Gold marvels. “We were fighting a war, and they felt such a responsibility. We sent well over a thousand families to seminars from this area. Dozens and dozens of families became baalei teshuvah as a result.”

As Afula’s native religious population began to mushroom, more and more people from outside began hearing of the kollel’s success, and began moving in. Soon there was a critical mass of frum families for whom the local education options were inadequate. They cornered Rabbi Gold, saying they were very happy to be contributing to the chinuch at the Marom outreach school, but asking why their own children had to suffer without a local cheder.

Rabbi Gold agreed to take on the challenge of helping them open a Talmud Torah. He had secured funding for his other endeavors through personal solicitations, foundation grants, and taking out substantial loans, but he now saw the need to tap other sources. He ended up running for Afula’s city council, on the Degel HaTorah ticket, for the purpose of securing municipal funds for the burgeoning religious population.

“I’m still there,” he says of his elected office. “It’s not such a groyse kavod.”

One of Rabbi Gold’s kollel avreichim, Rabbi Yisroel Greenstein, took charge of putting the Talmud Torah together. From his perch on the city council, Rabbi Gold was able to procure caravans and buildings for the nursery and kindergarten.

The cheder grew rapidly and today counts a student body of about 450 students.

“Rabbi Greenstein is independent now, and he’s doing a wonderful job,” enthuses Rabbi Gold.

Rabbi Greenstein recalls those early years fondly, especially the eclectic student mix.

“We had one father from Kfar Gidon who asked if he could bring his son on a donkey every day,” Rabbi Greenstein says. “He would bring his son on the donkey, park the donkey on the side, and the son would come and learn. That kid had a good head, he learned well.”

When the municipality first provided the caravans, they came with some interesting strings attached. Or rather, not attached.

“When the cranes were setting these caravanim down, we were afraid they were going to fall apart,” says Rabbi Greenstein. “And then, the city wouldn’t connect them to the electricity. The kids had to learn in the dark, in the heat. But they learned with such simchah, b’shirah, in song. It was really something. A very special atmosphere, mishpachti me’od [very heimish].”

The yeshivah ketanah, for bochurim just finishing cheder, just opened a few weeks ago for Elul zeman —even though it seemed there was insufficient demand.

“We went to Rav Gershon Edelstein for a hora’ah, we explained we didn’t even have a minyan for the bochurim,” Rabbi Greenstein says. “He said go ahead and open it anyway, fill out the minyan with avreichim. It’s important for the bochurim from Afula to learn in a yeshivah close to home.”

Other educational institutions have sprouted up along the way. Demand for a girls’ school led to a Bais Yaakov. Today it counts 150 girls. There is also now a midrashah for the older girls; Rabbi Greenstein’s wife is the menaheles.

Demand for a local yeshivah gedolah, interestingly, came from outside the city, and its opening came about through a negotiation Rabbi Gold held through intermediaries with the gadol hador, Rav Aharon Leib Steinman ztz”l. A group of avreichim investigating affordable housing options checked into Afula, and found it suitable except for one flaw: the lack of a yeshivah gedolah. They approached Rav Steinman, who communicated through them to Rav Gold that if he would take care of this one shortcoming, Rav Steinman would send families to Afula.

“Gold kept his word,” Rabbi Gold says proudly. “And you know what? So did Rav Steinman. He sent several families, around six years ago. The yeshivah started with about 20 bochurim, now there are about 170, and it’s a fantastic, high-level yeshivah.”

W

hereas the older parts of Afula, down in the valley around the city center, give the feel of a drab, run-down 1950s Israeli development town, dominated by hulking masses of Brutalist concrete architecture, the neighborhoods of Givat Hamoreh and Afula Illit were built as the city expanded across the plains and up the hills to the east. There is a distinctly suburban, low-density feel to these sections, and vantages down the treelined streets open onto commanding views of the Jezreel Valley.

The revolution is headquartered in a shul in Afula Illit. Here is where the kollel learns every day during the week. The shul is called Heichal Hashivah, “Hall of the Seven.” The shell of the building was originally erected by the city to honor the memories of the seven victims of a 1994 bus bombing that ripped through the center of town, in the wake of the Oslo Accords — but that shell stood empty for 15 years.

The sight of the hollow, empty building haunted the families of the victims until they appointed a representative to approach Rabbi Gold with an offer: secure the funding to finish off the shul, put up a plaque in honor of the victims, and the shul is yours.

“Now it’s open, and it’s packed — we have no room for people to stand on Shabbos,” says Rabbi Gold.

The kollel is headed by Rav Yitzhak Amrani, originally from Har Nof, Jerusalem. One of the avreichim here, Rabbi Shalom Ben Ezra, has stepped into the role of organizational lead for the kollel’s kiruv activities.

“The basis for the whole community is 150 baal teshuvah families,” Rabbi Ben Ezra explains. “Now other people are starting to move here — Rav Steinman sent some families, and Vizhnitz has established a presence here. We didn’t necessarily bring them here, but the point is, they found the ground already prepared for them.”

He gestures to the beis medrash in the shul where the kollel is in session. “The whole revolution you see happening in this community has its center here. The baalei teshuvah who have learned in our kollel are now paying it forward by learning with other secular people here in the community. The stories we hear about their impact are just amazing — whole families turned over completely.”

He goes on to list a few of the activities: “We have avreichim giving regular shiurim in secular people’s homes that draw dozens every week. We have avreichim doing outreach to the surrounding yishuvim. One of them grew up in a local yishuv, got married, learned in Yerushalayim for a while, but came back here. Three times a week he gives shiurim on different yishuvim in the area.

“We have two avreichim here who saw that there’s not enough manpower. They gave personal donations. They took more avreichim and opened here, twice a week, a place to learn with local secular youth who are serving in the army. There is another avreich who learns with local balabatim three times a week. One gives a shiur in the fire station. That eventually evolved into a shul — in the fire station.”

He gazes off toward the rows of new standard-issue apartment buildings rising in the valley below. “I would happily go and bring these activities to all the people who will fill these apartments, but I don’t have the money or the manpower. I know Rabbi Gold would like very much to do this.”

He gestures back toward the shul. “Each new person I accept into the kollel will eventually bring back 100 Jewish families. We see here that anything is possible — we just need the manpower. That is my constant request to Rabbi Gold: Just give us the resources, we will take care of the rest.”

Rabbi Gold gives full credit for everything that the kollel has accomplished to Rabbi Ben Ezra. “He’s the engine here who makes everything happen. He is their prized possession. His organizational and administrative qualities… he’s incredible. He’s doing an unbelievable job.”

An avreich named Yehonatan Machlouf joins the conversation. It emerges that he is the one who gives the regular shiur in the fire station. He says he had gone there and seen that it was “possible to save neshamos.” His main objective in starting the shiur, and then an evening kollel, was to build chivuv, endearment, between the chareidi community and the secular public.

“I wanted them to see that we love them, we care for them,” says Rabbi Machlouf. He has since opened another kollel on the same model in a different location on the other end of town. The enthusiasm is infectious.

“The avreichim who come work for us see the effect they’re having, and they’ve never seen anything like it,” he says. “They say they want to open more kollelim. I tell them, go ahead, do it — yagdil Torah!”

The discussion is joined, fortuitously, by two men in the community who have benefited from the kollel’s outreach: local real estate agents Yizhar Azoulai and Nir Levy. They both heaped praise on the avreich who drew them in, named Rav Yaakov, who started giving a shiur in a pub, of all places.

“I wasn’t always shomer Shabbat — I started when Rav Yaakov came,” says Yizhar. “When Rav Yaakov came in, through the activities of the shul here, he completely lifted up the spiritual status of this area. Before, if I had a question, there was no one to ask. He came in and he approaches people at their level, where they’re holding.”

“I come to the shiur in the pub,” says Nir. “I come there every night for drinks and dancing. But before that I’m hearing divrei Torah, an hour with Rav Yaakov.”

Rabbi Gold breaks in with a question of his own, for Nir: “What kind of people come to the shiur in the pub? Men with beards and peyot?”

Nir laughs. “No, but we’re learning about the mesorah, and I am mitchazeik from the shiurim. Baruch Hashem that Rav Gold came here — all that you see wasn’t here before.”

Another creative avreich named Rav Tzachi set up a bomb shelter to host a weekly Oneg Shabbat till one in the morning, offering such enticements as billiards and ping-pong. That brought in Negev Kraus, who grew up in a single-parent home with an economic situation he describes as “not easy.” But Negev looked forward to the weekly oneg, which regularly drew 30 to 50 youths in the area.

“I was not religious at all — not even tefillin,” Negev says.

“Sephardi bli tefillin, zeh mamash rachok! [A Sephardi without tefillin, that’s really far!]” interjects Rabbi Gold, reiterating a point well known among Israelis that even Sephardim who self-identify as nonreligious often lay tefillin daily and daven three times a day with a minyan.

“But I started learning with Rav Tzachi,” says Negev. “I’m still friends with him today. I’m frum now 12 years, shomer Shabbat, learning Torah, and my kids learn in the Talmud Torah.”

After parting from Negev, Rabbi Gold points out the lengths to which the kollel had gone to reach him. “That group he was part of was really on the fringe. Very dysfunctional, no fathers, their homes were in abject poverty. It wasn’t only a lack of Yiddishkeit; they had no life.”

W

hile Rabbi Gold’s Mashma’ut organization has built up an impressive track record over the years in Afula, at the very beginning he ran into some concerted community opposition that nearly derailed his initiatives. The principal of the local public school organized neighbors against Marom, and complained to the mayor that his school’s children were being spirited away by Rabbi Gold. The local newspaper ran articles against Rabbi Gold, and he wondered if he would be able to keep it going.

“But then you go into a classroom, seeing these yingelach who don’t know anything about Yiddishkeit saying Shema, and you just get this feeling — it’s all got to work out,” he says. “Every time we thought this was the end, something would suddenly come from left field, and we’d manage to stay afloat. Hashem’s making us sweat, but we can sense that He’s watching over us.”

Sometimes the opposition was more personal. The Golds’ Shabbos table regularly includes guests from the community, very often young people. When he first began tendering invitations for Shabbos meals to secular teenaged boys — “you know, the ones with the earrings,” he says — he found himself cross-ways with one of the parents.

“A knock came at the door,” he says, “and when we opened it, there stood a father of this boy we had invited. He pointed his finger at me and said, ‘Don’t you dare ever bother any of our children again or we will run you right out of town.’ ”

Undaunted, Rabbi Gold stuck to his plan and over time, those kinds of reactions dissipated. “After a while they saw that I’m a shtickel nice guy. That father is one of our greatest friends now — he’s an engineer for the city and he’s been tremendously helpful in getting our projects approved.”

Rebbetzin Gold is happy to have moved past the social isolation of being American and frum in a Sephardi, mostly secular city. “Our children were quite lonely while they were growing up,” she admits. “The older ones basically had no friends until they went away for yeshivah and high school. The younger ones managed to make a few friends with kids from local families who had become baalei teshuvah, or from frum-from-birth families who had moved in.”

That loneliness was compounded by Rabbi Gold’s frequent lengthy trips abroad to raise funds for his institutions. “I had to import older children to stay with us, either relatives or from friends’ families, so I would have some help,” Mrs. Gold says. “My husband still goes for fundraising now, but like with everything, you get used to it.”

The family developed certain survival strategies to make life more bearable; they mainly took the form of trips to Jerusalem, to buy special foods not available in Afula, and in the early years, for every single chag. “We kept that up for many years, but in the last few years we spend most Yamim Tovim in Afula. We find that we still need to be in Jerusalem for Purim and Shavuos, though.”

Despite the rough patches in those first years in Afula, and despite the daily challenges that still come up — like the lack of suitable local clothing stores — Mrs. Gold feels at peace now with the family’s move.

“After seeing the fruits of your labors, you get a different perspective on living in this place,” she says. “When we’re out, we meet these young men in their twenties and thirties who all know my husband. They’ll tell him how he used to play soccer with them when they were kids, from broken homes and dysfunctional families. Now they’re frum, married, their wives are covering their hair, their children are in cheder… It’s just really nice to hear.”

Now, ironically, if the opportunity were to arise to move back to Jerusalem, she says she would likely pass it up. “I just feel like we can’t leave. We have to be here.”

R

abbi Gold’s second-oldest son, Binyamin, whom everyone calls Benny, is now a 28-year-old married kollel avreich learning in Yerushalayim. But he grew up in Afula, at the center of all the activity of the last two decades that his father describes. He is grateful for the experience.

“When I look back, even though there were times it was very hard, I feel I want to tell my parents thank you,” he says. “When you grow up in a city that is mostly non-frum, you get all your chinuch at home. You are taught how to deal with the negative influences outside. This is very different from how a child raised in a chareidi neighborhood gets his chinuch. My parents dealt with everything in such a strong and healthy and caring way. My siblings and I absorbed it all 100 percent. I think I speak for all of us when I say it was like a present they gave us.”

Benny continues to play a key role in his father’s endeavors, especially in the large food distributions that take place before Yamim Tovim. “We want to make sure not one family goes into a chag without food,” he says.

In that capacity over the years he has become a familiar face to Afula residents, such that he even acquired the moniker “Harav Binyamin” as a bochur, from people wanting to convey respect toward his family. “I managed to get semichah without becoming a rabbi,” he jokes.

“When mechanchim go to these out-of-the-way places, they have a special brachah,” muses Rabbi Menachem’s father, Rabbi Sholom Gold. “Hashem protects their children.”

Having said that, the elder Rabbi Gold puts his finger on a couple of other factors in his son’s success. “Nothing stops him, he keeps going under the most difficult of circumstances. It was his relentlessness and siyata d’Shmaya that allowed him to make a dramatic impact.

“And he never is interested in getting credit for anything. He just wants to get things going, he has no need to be a balabos or a rosh yeshivah. As the saying goes, ‘It’s amazing what you can accomplish if you don’t care who gets the credit.’

“He’s done an amazing job. He dramatically changed the complexion of the city. He is a lesson on the koach of an individual, what one person can do.”

Carrying All the Worlds

R

abbi Gold offers to take us to meet the mayor of Afula, whom he has gotten to know well through his service on the city council. On the short walk down a commercial pedestrian mall running through Afula’s compact downtown to the municipality offices, people from every walk of life stop Rabbi Gold to give him greetings and family updates — a kollel avreich, a middle-aged shopkeeper, a secretary out for a lunchtime shopping errand. Everyone here seems to know him, including the city hall staff who welcome him warmly to the mayor’s office. We are soon ushered into the inner sanctum.

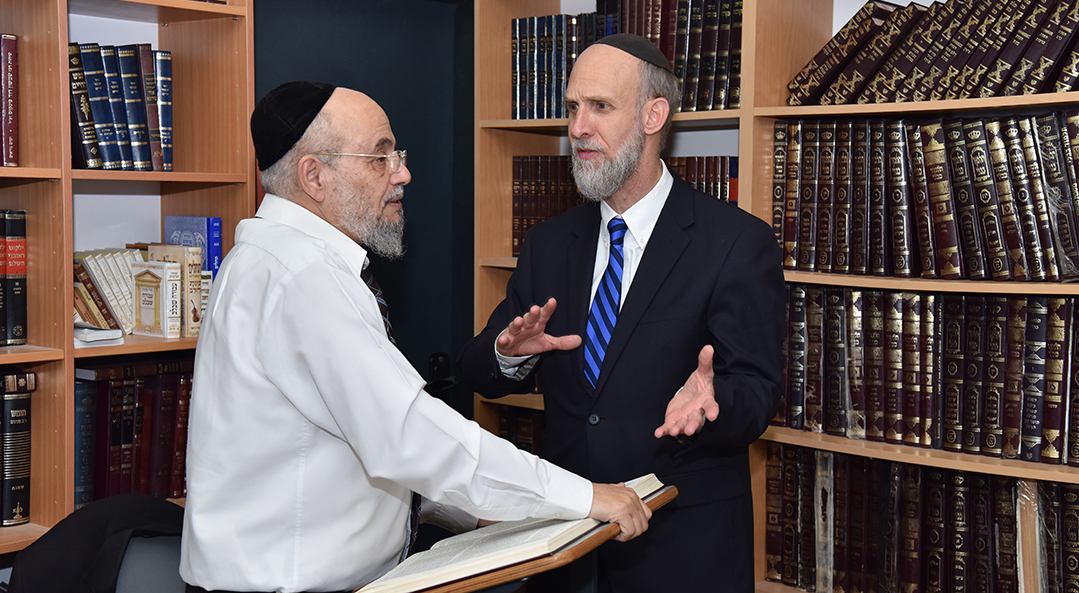

Mayor Itzik Meron (pictured on right) speaks in the resonant baritone of an Israeli radio announcer. He delivers a rhapsodic paean to his home city, where he was born and raised and where he has served in public office for some two decades. The population is very diverse, he says: the original Moroccan settlers made room for newcomers from the former Soviet Union, and accommodated a wide range of religious observance. He points out that the town has by and large been secular, although in the last ten years the religious sector had increased significantly.

“Ad she’Gold higia v’haras et hachagigah,” quips Rabbi Gold. (“Until Gold arrived and spoiled the party.”)

The mayor laughs and says that although some recent “ultra-Orthodox” arrivals had been more “self-contained,” keeping mainly to themselves, Rabbi Gold exemplifies the best of the religious community. “He is a person who carries all worlds, the chareidi world as well as the secular world. He is accepted by everyone, here and there.”

Mayor Meron contrasts the attitude in his city with that of other more fractious polities, which he said are plagued by a lack of tolerance. “The tradition here in Afula is more tolerant, live and let live.”

The mayor goes on to enumerate Afula’s many advantages — its strategic geographic location in the north, its climate and low cost of living — and describes some of the city’s development plans for the future, including a high-tech industrial park and, potentially, the planned location for Israel’s second international airport.

It is clear that the people of Afula hope to welcome many more new arrivals in the future, with open arms.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 729)

Oops! We could not locate your form.