Adams’ Apple

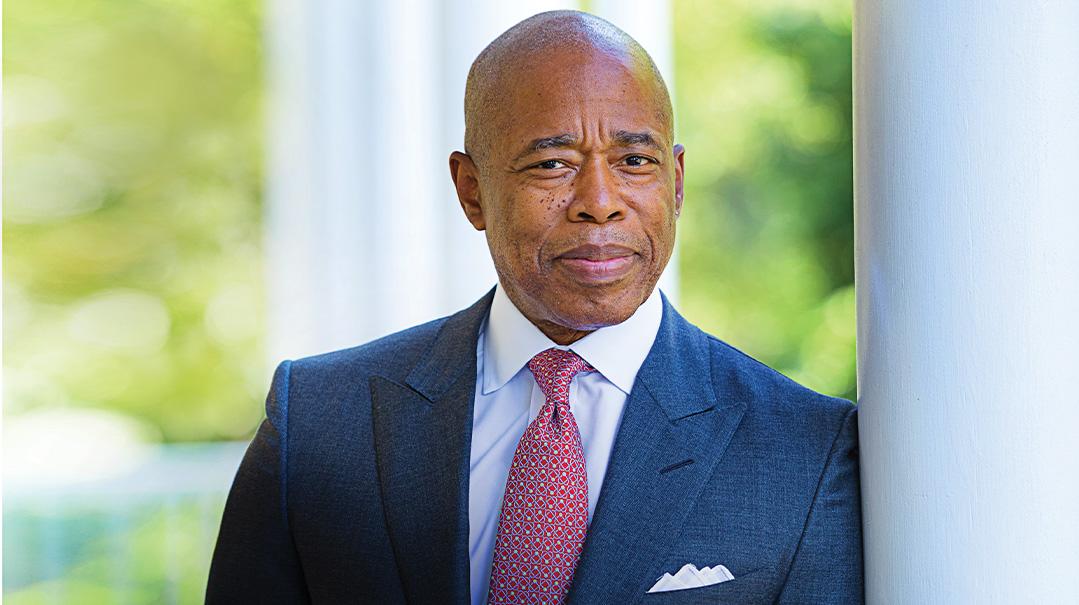

Can Mayor Eric Adams reverse the rot in New York City?

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab, AP Images

Until a few years ago, Eric Adams was a cop carrying a service revolver. Now that he’s New York’s 110th mayor, he has a secret weapon.

Swagger.

It’s obvious in his frequent, confident smile; it expresses itself in the flamboyant cut of his clothes; and it works its way into speech that’s heavy on colorful aphorisms and wordplay.

“I will never forget that my glory is not my story,” he said shortly after taking office. “I only had a badge as a cop because my mom used a rag and a mop to create a better future for me.”

The bonhomie is very different from the dogmatic tone adopted by his predecessor, Bill de Blasio.

But eight months into his term as mayor, Eric Adams needs all the swagger he can lay his hands on. The city is still recovering from a brutal encounter with Covid that led to a cycle of lockdowns and restrictions. Two years ago, the world was shocked by footage of tony designer stores in Midtown Manhattan boarded up during the George Floyd riots.

New Yorkers are now watching a near-daily dose of videos of people being randomly punched on trains, assaulted in buildings, and shot at on streets. When everyone is a photographer, the recent rise of store robberies in broad daylight and “smash and grabs” along busy streets has led to an overall feeling of lawlessness.

Mayors get judged by whether the garbage gets collected or the streets are plowed, but when crime rates tick up, it crowds out every other concern.

As an ex-cop, Adams was elected to restore a sense of safety to a city buffeted by a violent crime wave. But since coming to office, major crime has jumped by 36 percent compared to last year.

That grim number is making itself felt in polling across the city. A Siena poll taken before the start of summer found that 76 percent of New Yorkers are anxious they will be the victim of a crime while out and about in the city. A 56 percent majority says the Big Apple is headed in the wrong direction.

As for appraisals of the mayor himself, the results are mixed. His job approval rating is below 30 percent, with 64 percent considering his performance fair or poor.

As he sips water from a glass emblazoned with the city seal, Eric Adams seems unworried by these perceptions. He thinks New York’s human capital will see it through the latest downturn, and the city will bounce back.

“I believe,” he says, “that in order to solve a problem, you have to see yourself through a problem, and not believe that where you are is who you are. Sometimes people are pessimistic with my optimistic view of where we’re going.”

Wordplay — sometimes glib-sounding — is part of what makes Adams tick, but there’s an impression that the mayor sometimes uses his verbal dexterity to duck and weave to avoid tough questions.

Eric Adams disagrees. “When a mayor has swagger,” he said days after taking office, “the city has swagger.”

Adams told Mishpacha’s Yochonon Donn how his mother cleaned houses, and how he, a learning-disabled child who spent his teen years in precinct holding cells, was sure his bleak future was already decided. “That’s why at public events,” says his aide, “the first people he goes over to are the waiters. He puts his arm around them and encourages them. He relates to these types of people”

Crime and Punishment

Adams ran for office as a tough-yet-compassionate ex-cop who would take the fight to crime in New York — and he certainly has a fight on his hands.

Two defining characteristics of the post-Covid era are auto theft and the phenomenon of smash-and-grabs. Both have seen eye-popping increases over last year’s figures since Adams took office on January 1: Grand larceny was up a whopping 48 percent, from about 20,000 incidents to 30,000, while auto theft escalated 42 percent and robbery jumped 40 percent.

Even the good news is couched in negative terms. Murders were down eight percent, from 284 to 261, and shooting incidents dropped 10 percent, from 938 to 843. But the decreases were a regression toward the norm, after the unusually sharp rises in these categories the year before. Compared to figures from five years ago, the number of murders was up nearly 50 percent. The de Blasio administration’s kid-glove handling of crime, statistics show, eviscerated more than 10 years of crime reductions.

Adams, says Hank Scheinkopf, a prominent Democratic consultant based in New York City, is from the small group of modern-era mayors of the city who are confronted with intractable problems on Day One.

“He was handed a terrible set of circumstances when he came into office. And he has to deal with that,” Scheinkopf says. “He inherited one of the most extreme set of circumstances of any mayor, and he’s had to function with it.”

Scheinkopf says that of the post-World War II mayors, Adams could best be compared to Ed Koch, who came into office with the city finances under state oversight, there were thousands of murders every year, and people felt the city was ungovernable.

“There is no question that they have a lot in common in their styles, with that same sense of enthusiasm, love for the city, and belief in its future,” Scheinkopf says. “Mayors of New York City are by their very definition international figures based on how they rise to crises. Some mayors inherit crises when they walk into office, like La Guardia or John Lindsay. Abe Beame had a crisis he didn’t want to deal with, the fiscal crisis. Giuliani, Bloomberg, and Adams — all of them walked into crisis, and they are measured by how they managed that crisis.

“Bill de Blasio walked into a very good set of circumstances — the city was flush with cash, crime was down, things were under control — and he messed it up. Adams’s crisis is cleaning up the mess de Blasio made. And he will be judged by how he deals with that.”

Adams wasted no time putting his public safety team in place after assuming office, and he has not been averse to trying new strategies right away, regardless of whether or not they are tested. The mayor appointed Keechant Sewell as his police commissioner, poaching her away from the Nassau County Police Department, where she had reached the rank of chief of detectives after 25 years of service.

But Adams, an ex-cop who made his profession a key selling point to crime-weary citizens, knows he has to go beyond making smart hires. He has expended political capital on nudging Albany to allow judges to hold suspects based on their “dangerousness” to society, regardless of the severity of their crimes.

Several of his crime-fighting schemes have fizzled quickly. Others succeeded, although he withstood withering criticism from social justice warriors and mockery in the press. He once proposed to double the number of cops patrolling subways to convey a sense of the “omnipresence” of law enforcement. This, he said, would make riders feel safe and throw potential criminals off balance. He countermanded that weeks later and said transit cops would instead go solo, to increase the number of patrols.

Just last month he ordered officers not to chat with each other while on the beat. The media had a field day, posting pictures of officers talking while on duty.

Progressives balked when he brought back the specialized anti-crime unit, which de Blasio disbanded over allegations its plainclothes officers used excessive force. Adams says he wants to refocus it as a strictly anti-gun force in select neighborhoods that have a glut of illegal guns.

Ultimately, Adams’ goal is to bring back a feeling of safety to citizens. That is not easy, coming after the chaos of the last two years. “We’re not going to surrender to those who are saying, ‘We’re going to burn down New York.’ Not my city,” Adams said at a Police Athletic League event shortly before his inauguration.

“There are individuals who have basically made up their minds that they’re not going to follow laws in our city.” Adams wants to allow judges to lock them up

Battling the Bad Bail Law

Gracie Mansion, where our conversation takes place, is famous for something else as well: In 1801, Alexander Hamilton gathered the New York Federalists here to raise $10,000 to establish a newspaper called the New York Evening Post, the forerunner to the New York Post.

The Post, in its current form, has proven to be a pox on residents of its founding home. It ridiculed de Blasio mercilessly, regularly placing him on its cover wearing a clown costume. But the paper has been relatively kind to Adams, endorsing him as a “vote to save New York” due to his opposition to the state’s controversial bail law, which passed in 2019.

The bill, deemed a “reform” by its progressive authors, removes discretion from judges to hold a wide array of suspects on bail, resulting in a jailhouse revolving door that returns criminals to the streets within hours of arrest. A recent Post front page graphically highlighted Adams’ call for bail reform with its headline — “Ten people, 945 days, 485 crimes (and most are still free).”

Just as the city has statistics for how many cabbies or lawyers operate, it also knows how many criminals ply their trade. Adams said at a recent press conference that 761 felons are responsible for 30 percent of all crime in the city. I asked Adams what the city is doing to crimp their business.

“These are individuals who have basically made up their minds that they’re not going to follow laws in our city,” he responded, before pivoting to his call for allowing judges to lock these people up. “When you look at the volume of crimes, the disproportionate number of criminal acts they carry out, by such a small number of people — it says a lot about our criminal justice system. And so the reforms that took place in Albany, many of them hit the mark — they were the right things to do, and people are learning their lessons.

“But there’s a small number of people — 10 percent, probably — who have made up their minds they’re not going to follow any rules. And as long as they exploit the reforms, they’re going to continue to perpetuate violence on the people of the city. So we’re saying, let’s reexamine those laws that were passed, to grab those who are exploiting them so we can hold them accountable, so our city can be safe.”

Governor Kathy Hochul, who is in an election year, has been straddling the fence on this issue, saying she understands Adams’s arguments but insisting the law already allows judges that discretion. She hasn’t responded to Adams’s declaration that the law does not and needs to be changed. Regardless, leaders of the Assembly and state senate have said they have no plans to alter it.

The two Democratic lawmakers representing Boro Park who voted against the bail law in 2019 told me that while they agree with Adams that it must be revised, the mayor was not fully utilizing all the tools available to him to fight crime.

“I agree,” said state senator Simcha Felder, “that the bail reform bill is a bad thing and hurts law enforcement — I was one of just two Democrats who voted against it — but everyone understands that that is not the only thing that brings down crime.” He mentioned the “broken windows” policy of vigorously pursuing minor crimes as a way of deterring criminals from committing graver felonies, and the stop-and-frisk program.

“Broken windows” policing became a fixture of the Giuliani administration’s successful effort to lower crime rates. His successor, the data-obsessed Michael Bloomberg, focused on stop-and-frisk, under which people acting suspiciously would be stopped by an officer and questioned. If the cop suspected wrongdoing, the person would be frisked. Both policies were ended by de Blasio, who claimed that they were racist, since most people getting caught in their net were blacks.

“I’m not a crime expert,” Felder added, “but everyone understands there is more than one tool to fight crime. Bail reform made it very difficult to fight crime, but that doesn’t mean that you throw up your hands and say, ‘Okay, if I don’t have that, then there is nothing I can do.’ Before the bail reform, crime was already on the rise as a result of Mayor de Blasio getting rid of stop-and-frisk, ‘broken windows,’ and a lot of other police initiatives. The mayor should bring those things back.”

Assemblyman Simcha Eichenstein noted that the reason criminals were getting released right after being booked was not solely due to the bail law.

“Don’t forget, there are prosecutors who are not prosecuting and judges who are not holding suspects on bail when they could do so,” Eichenstein said.

Ex-cop Adams and the former mayor. Analysts say that Adams’s crisis is cleaning up the mess de Blasio made, and he’ll be judged by how he deals with that

The Adams Doctrine

The Adams administration is taking the middle of the road on this, adopting a tough-on-crime posture and simultaneously performing outreach to rough neighborhoods. How, I asked, is it working?

“If you go through life and you don’t learn in the process,” the mayor said, “then you didn’t really go through life. There were aspects of every mayor that I learned from. I watched what they did — some things I agree with, some things I disagree with. But one thing is clear. We don’t want to criminalize communities based on their zip code or based on their ethnicity. But we also can’t turn our backs on the fact that there are those who are extremely violent, and we must respond to that accordingly and ensure that they do not continue to harm innocent people.

“So I’m borrowing parts from every mayor who served. I’m learning from them all. I read all of their books and I learned from their most challenging moments.”

He is taking the interventionist path from Giuliani, targeting bad behaviors before they turn criminal, and the road of prevention from de Blasio, providing alternatives to youths so they do not fall into gangs. For example, he increased the number of Youth Corps slots this past year by 25 percent, to 100,000, offering wages to youths who get summer jobs.

“I’m a believer in dealing with quality of life issues so they don’t escalate to criminal activity,” Adams said. “But I also believe that we should have things in place to prevent criminal behavior. And that is the right combination. I like to call it intervention, which we must do right now, and prevention, which we must do in the long term.”

A couple of decades ago, California passed a “three strikes law,” which allowed judges to hand down life sentences to anyone convicted three times, even for petty crimes. California being a liberal state, it has since been canceled. The political will in New York for such a law is lacking, but how about 30 strikes and you’re out?

Adams laughed at the suggestion, but said he would not support such a law.

“The number of times you commit a crime is not the right indicator. You could do three crimes, but if you have the clear propensity for being violent, that judge should be able to make that call on the bench. Forty-nine states have what’s called the ‘dangerousness provision.’ Isn’t it odd that New York state is the only one in the union that doesn’t have that? We’re saying, give the power to the judges, monitor them, give them proper training. We need to empower judges to say, ‘This person in front of me, from all the evidence I have, given my professional opinion, should not be released to continue inflicting dangerous acts on the public.’”

Dangerousness, Adams clarified, is a legal term that is based not on a criminal’s prior actions but on what he potentially could do.

“A judge right now must determine that if he’s going to release someone, then he does so in the least restrictive way,” Adams said. “So you have a person standing in court who you know is dangerous, but you have to release him in the least restrictive way possible. That just does not make sense. We don’t look at the fact that this person may have been arrested before and has not returned to court. When you don’t come to court, you get a bench warrant, and some of these people have a number of bench warrants. If you’re not taking all that into account, you’re not making the right decision.”

Although reducing the crime wave will require several factors beyond his control to come together, Adams says he’s fiercely optimistic that the city will overcome this challenge, just as it has triumphed over other problems in the past.

“This will be another milestone on the road of the evolution of New York,” he says. “We’re going to get through Covid. No one thought when we were in the shutdowns that we were going to get through Covid, but we did. No one thought, when we were going through the store burnings on Broadway during those riots, that Broadway was ever coming back — try to get a store on Broadway right now, or in Brooklyn. And so I know that we’re going to recover, and we’re going to become bigger and better than ever. We must get everyone on board physically with the recovery, but also mentally.”

His optimism, he says, comes from living in the city, but also understanding its history. “This is a city that went through the Great Depression. This is a city that has gone through riots, it’s a city that has gone through terrorist attacks, a city that has gone through high crime waves — during the mid-’80s and early ’90s, we saw over 2,000 homicides a year. So if you understand the history of the city, you realize that we’re successful not because we have the Empire State Building or Broadway — we’re successful because of the people. And if those same people made us successful in the past, then why wouldn’t they make us successful again?”

Adams also draws optimism from his own experience, growing up as a dyslexic child whose path in life nearly veered to crime.

“My mother cleaned houses. I washed dishes,” he said in his inauguration speech. “I was beaten by police and sat in their precinct holding cells, certain that my future was already decided. And now I will be the person in charge of that precinct and every other precinct in the city of New York, because I’m going to be the mayor of the city of New York.

“There may be a young person out there right now who believes they’re not smart enough to go to college and to succeed. I did too. But I overcame a learning disability and went to college and was able to obtain my degrees. And now I will be the mayor in charge of the entire Department of Education.”

An aide tells me that the part Adams loves the most about his job is the ability to lift people up. He obliges many requests to record well-wishes for birthdays and weddings, a privilege many in New York’s frum community have availed themselves of.

“Do you know where he goes first whenever he’s at an event?” the aide tells me. “To the waiters. He goes over to them, puts his arm around them and encourages them, tells them that they’ll go up in life. He relates to these types of people.”

Eric Adams said he’d love to move to Israel when he retires. It might have been a joke, but he insists it’s still on his agenda

Making the Cut

New York City mayors have a curse, it is said. They never ascend to higher office, despite the position’s reputation as the second-hardest job in the country. This is at least partly because of the infighting that usually brews between Gracie Mansion and Albany — the mayor needs the governor’s permission for almost everything, from raising taxes and installing speed cameras to running the schools and changing the city’s charter.

The infamous Cuomo/de Blasio brawls, while wilder than usual, can be chalked up to their personalities — a vindictive governor and a mayor who perpetually thought he was right. Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul are both much more mild-mannered and have succeeded in maintaining cordial relations, despite the potential for disputes inherent in their roles.

Adams had much less success when he sought to assert power in a more traditional way. He endorsed eight centrist Democrats for state races in last week’s primary election; three lost in landslides to progressives. Aside from the embarrassment those defeats caused the mayor, they riled up the party’s left wing.

“Adams’s endorsement isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on,” crowed progressive consultant Gabe Tobias.

But just because he loses one fight doesn’t mean he’ll shy away from the next one. Adams was in the thick of another political fracas at the time of our conversation. His budget for next year, approved by the City Council, cuts the education department by $215 million — off a total budget of $31 billion, less than one percent — due to declining student enrollment following the pandemic.

Teachers organized a group of parents and filed a lawsuit. The group then initiated a campaign targeting the council members who voted for the cut. One by one, those council members capitulated, apologizing for their votes and claiming they didn’t realize its impact. Council Speaker Adrienne Adams — a high school classmate, but not relative, of the mayor — demanded that he restore the cuts.

“We had a great exodus,” Adams affirmed, blaming it on Covid policies that shut businesses and kept children from in-person schooling for nearly two years. “When you really look at the numbers, the largest number of students in public school are black and brown. The largest number of people who left the city are African Americans. The city has been unaffordable, too expensive, and they went to other places to live. And so there has been a great migration, a great departure.

“Now look at the new arrivals. The new arrivals are young, they don’t have families, they don’t have children, or they are having a smaller number of children. So it’s not an equal one-for-one, where one family departs and another family comes in — it’s just the opposite. We must adjust to this new norm. Education funding is determined by how many students we have, and when you have a lower school population, based on that, we have to adjust funding.

“What does that look like? Years ago, we had 1,000 students in a school. Now we dropped down to 750. Do we still give the same funding based on the decrease in student population? The federal government is not going to give us the same money, the state is not going to give us the same money, so we have to adjust to that new norm. We want to do it in a gradual way. We didn’t take away all the money at one time. We’re saying to our principals and educators, there’s a new funding reality that we have to face.”

Ultimately, a judge ordered the Adams administration to restore the funding and scheduled a hearing for this past Monday. But I asked Adams what political lesson he drew from the battle.

“Every dollar that a child was supposed to get, we’re doing that,” he emphasized. “What happened is that the student population dropped, so we’re right-sizing the funding for schools. The city council members, with all of their staff, they read it, they understood what it was. You can’t come back later and say you want to redo the budget. That is just not how our system of government operates.”

The council said that the city could use federal pandemic grants to pay the extra money, just as de Blasio did last year. Council Speaker Adrienne Adams said that the severe disruptions Covid made for children meant that more services and mental health counseling was required. Some budget experts have proposed targeting funding to schools with high-needs students and cutting the money in other schools, which would allow both sides to declare victory.

But the mayor insisted that he wanted to use the federal grant money for other programs.

“My mom used to say, ‘A deal is a deal.’ We made a deal,” he said. “ ‘Promise made, promise kept’ is not just a slogan, it should be how we live.”

We Need Your Voice

Adams hopes to bring the same determination with which he fights crime and budget busters to bear against another pernicious issue: rising homelessness in the city. The sad human crisis stares New Yorkers in the face every time they leave home. Women and children know to avoid certain blocks where homeless people lie on the sidewalk. De Blasio took the stance that homelessness is not a crime, and nothing can be done about it if people refuse to enter shelters.

“There are layers to the problem,” Adams concedes. “First of all, this is decades in the making. And it’s also a national problem — Washington, D.C., Chicago, Los Angeles, all our major cities are dealing with homelessness. We need to come up with a solution that’s going to deal with a decades-old problem. We do that by not resorting to quick, easy, politically correct fixes.

“Number one, we need voices from the public. When I came out with my homeless initiative, there was a lot of criticism from those who are the loudest. But everyday citizens must stand up and say, ‘This is not what we want in our city.’ I’m not going to advocate and I’m not going to have policies that allow people to sleep in an undignified manner on our streets.”

Adams’ homelessness initiative would add hundreds of more beds to safe haven shelters, and increase the number of police sweeps to dismantle homeless encampments, applying a carrot-and-stick approach to move homeless people off the streets.

The initiative started in the subway system. The first week saw 22 people agreeing to head into shelters, a total that has now ballooned to over 1,700, Adams says. The same program is now being carried out with street homelessness. But he emphasized that the tents and portable baths caught on viral videos will not be allowed.

“We’ve walked by street homeless — those who lived in camps and tents — and I say no to that in this administration,” he says. “We can’t stop a person from sleeping on the street; that’s their constitutional right. But you can’t sleep in a camp, a tent, a makeshift house, we’re not allowing that to exist. We’re meeting it head on.”

The ambition behind Adams’ determination parallels that of another New York mayor — the “Little Flower,” Fiorello La Guardia, who defeated organized crime with his “let’s drive the bums out of town” campaign, and brought federal funding to build the West Side Highway, East River Drive, Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, Triborough Bridge, and Kennedy and LaGuardia airports. La Guardia also fought radicals on both ends of the spectrum.

Hank Scheinkopf says Adams has the right formula for becoming a great mayor, just like La Guardia.

“He’s out in the street with people, just like La Guardia, he’s speaking to New Yorkers, trying to convince them that they should not panic,” the veteran operative says. “And that is the mark of a great mayor, ultimately. Eric Adams is the only hope we have right now. The question is only whether the people in power in Albany will allow him to do what he needs to do to solve the problems.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 927)

Oops! We could not locate your form.