A Prince and a Servant

Reb Yaakov Rajchenbach never saw his assets as his own — he was merely a funnel for anyone in need

Photos: Chicago Community Kollel

He supported Torah institutions all over, he let others feed off his businesses, and he never saw the inside of a beis din, even if it meant losing millions. His recent passing has left a gaping void, especially in his home town of Chicago, Illinois, which he helped transform into the center of Torah and chesed it is today. But as nasi of Torah U’Mesorah, his reach went way beyond the city limits. That’s because Reb Yaakov Rajchenbach never saw his assets as his own — he was merely a funnel for anyone in need

One Friday night some eight years ago, a Chicago dining room hosting a shalom zachar was packed to capacity. But although the last available chair was taken while the guests kept pouring in, the beer and arbis lining the tables lay untouched. At the head of the table sat the zeide, Reb Yaakov Rajchenbach; this was his family, his community, it was everything he lived for, and he glowed with so much pride. The people were proud too, proud to be part of a community whose leaders cared so much.

Someone began to sing, a song not usually sung at a shalom zachor: “V’chol mi she’oskim, b’tzarchei tzibbur b’emunah…”

And suddenly, the mood shifted. The pride was still there, but now, there were tears, signaling an emotion few could describe but everyone shared. “Hakadosh Baruch Hu, y’shalem secharam, v’yasir meihem kol machalah, v’yirpa l’chol gufam…”

It was Shabbos and no one wanted to cry, but the words of the age-old tefillah seemed to have been written specifically for this moment. Just a few days earlier the ominous news had come out: Rabbi Yaakov Rajchenbach wasn’t well, and the doctors were giving him a few months, tops.

“Veyishlach brachah v’hatzlachah b’chol ma’aseh yedeihem…”

Those tefillos must have pierced the heavens because the doctors’ prognosis went unfulfilled — for eight years. The man who spent a lifetime enhancing so many lives would continue to live. He would continue to be that pillar of support for Torah institutions the world over. He would continue to be that listening ear and generous heart that had been the address for thousands in desperate need. He would continue to be a shining example of a true ben Torah, the humblest student at the service of his rebbeim. The doctors said he couldn’t, but he did.

Maybe because of the final phrase: “Im kol Yisrael acheihem, v’nomar Amein — along with all Yisrael, his brothers…” Yaakov Rajchenbach lived for his people. And so, in Shamayim, they said Amen.

Reb Yaakov, who never saw the inside of a beis din, knew his wealth was given to him to distribute to Klal Yisrael. So why fight over money that really isn’t yours?

Beyond Integrity

As the owner of a national lending institution, Mr. Brian Cory was a busy man. But this deal needed time and he cleared his schedule accordingly. He, together with his credit analyst, concentrated intensely as they carefully reviewed each document. It was a high-profile deal and the numbers all seemed to be adding up but there was one component to the deal’s structure that made no sense at all. Mincing no words, Mr. Cory looked up to face the client sitting on the other side of his desk.

“Mr. Rajchenbach,” he said sharply, “what in Heaven’s name is wrong with you?”

Yaakov Rajchenbach stared back, poker-faced. The banker pressed on.

“The other investor defaulted on this deal, Mr. Rajchenbach. He messed up, he didn’t perform! Now you hold the sole lien on this property — take it! Take the whole deal! Why are you offering to bail him out?!”

Yaakov Rajchenbach spoke deliberately. “I’ve been in business for 40 years,” he said, “I will never kick a man when he’s down.”

Albert Miller, a respected member of Minneapolis’s Orthodox community, was present at that meeting. “The defaulting investor in that deal wasn’t even Jewish,” he says, “and, had Yaakov done as the banker suggested, he stood to make a small fortune.” But he wouldn’t. Regardless of who the other investor was, Yaakov Rajchenbach didn’t hurt people. This wasn’t about chesed, it was about integrity. Yaakov Rajchenbach’s sterling character never swayed; it might have cost him millions but it earned him something greater.

When he passed away this summer on 8 Av, Albert called Brian Cory to inform him of the news. The seasoned financier sighed.

“I’ve been doing this for 45 years,” Cory said, “and I have never met a man with the morals and character of Yaakov Rajchenbach. I am very sorry for this loss.”

Stories like this one were so common in the world of Yaakov Rajchenbach that partners came to expect it. And it may have been about integrity, but at times it went well beyond that.

A group of investors, led by Yaakov, once put a significant amount of money into a certain business venture, but the venture dissolved rapidly and a fiery game of finger-pointing ensued. The banks were calling in their loans and the investors demanded that it be taken to the courts: Let the right man win; let the others suffer the consequences of a devastating loss. But one investor demurred. Yaakov Rajchenbach, leader of the investing group, held firm. “I won’t do it,” he said simply, “I’m not going to beis din or to court over this.” Instead, Yaakov sat down with the group and managed to convince them to pursue a settlement agreement with the banks rather than proceed with litigation. The case settled and, as far as the group was concerned, the story was over. But it wasn’t really.

Shortly thereafter, a good friend of the defaulted business owner received a phone call. It was Yaakov Rajchenbach and he had a question. “Listen,” he said, “this fellow’s business failed. What will he do about parnassah? Is there any way we can help him get back on his feet?”

A kiddush Hashem to the outside world, a never-ending flow of chesed to the inside world.

It’s a duality reminiscent, perhaps, of the very founder of our People.

Avraham Avinu’s tent was open to all and he transfused that chesed with the opportunity to teach the world about the beautiful truth of Hashem’s existence. At the intersection of chesed and kiddush Hashem, Avraham Avinu’s legacy was Yaakov Rajchenbach’s mission statement.

The Rajchenbach’s hachnassas orchim was nothing short of legendary. An unknowing driver passing through Chicago’s Peterson Park neighborhood might be confused at the sight of a constant flow of taxis parking outside a large corner home, complete strangers exiting and hauling suitcases up the front steps. It looked more like a hotel than a private home, but it was a private home — reserved only for those who belonged there. For the Rajchenbachs, that’s all of Klal Yisrael.

It wasn’t enough that they be given room and board. Like Avraham Avinu, Yaakov himself would preside over breakfast, curating a lavish spread fit for a king.

And it wasn’t only in Chicago. The Rajchenbachs owned an apartment in Florida where they liked to stay during visits to the Sunshine State, but it wasn’t always available. They allowed people to use it, free of charge, and that meant sometimes having to check into a hotel so as not to disturb their guests’ stay.

And just like Avraham Avinu’s hachnassas orchim beckoned the question, “Ayei Sarah ishtecha? Where is your wife, Sarah?” the answer, then as now, was, “Hinei b’ohel — She is in the tent.” Less public, but every bit as central. If Yaakov Rajchenbach stood out as one of a kind, with an unparalleled heart of gold, he met his singular match in his wife, Mrs. Judy Rajchenbach, tibadel l’chayim tovim.

As the wife, the akeres habayis, takes the role of “ikar habayis,” the primary element of the home, the bulk of the credit to the overflowing of Torah and chesed in the Rajchenbach home goes to Mrs. Rajchenbach.

With roshei kollel Rabbi Dovid Zucker and Rabbi Moshe Francis, and yeshivah builder Rabbi Sidney Glenner;

How to Say Goodbye

If Yaakov Rajchenbach’s persona carried echoes of Avraham Avinu, it’s something that came by way of inheritance. Because life wasn’t always this way. Yaakov was raised by parents who barely had any money at all, and that was the least of their problems. Yaakov’s father, Reb Yitzchok Rajchenbach, had been married before the war and had four children. He survived. They did not.

Soon after the war, he met a woman whose husband had perished in the Holocaust, while she, with her four children, had survived. The two got married and, in 1947, had a son whom they named Yaakov Eliezer. For his father, Yankele was a ben yachid — and for the newly married couple, he was their first step into a joint future that wouldn’t be haunted by the shadows of the past.

The family didn’t leave Europe immediately though. Little Yankele had fallen ill and the doctors advised them not to travel. They remained in Poland for what they thought would be a short time, but the country was soon overtaken by the communists and they were forced to remain. For the next ten years, the new blended family lived in Lodz, being raised as close-knit siblings, a relationship they maintained throughout their lives. But antisemitism reigned in Poland during those years and it eventually became unbearable. In 1957 the family immigrated to Eretz Yisrael where they lived for a year and a half. At some point, they felt that it would be better to move to America, and a relative in Omaha, Nebraska invited them to join him in his hometown.

Yaakov Rajchenbach was 11 years old when his family moved to Omaha. There, he attended a local public school until his bar mitzvah. Yaakov would vividly recall the moment when all that changed. It was Friday night, and his father turned to his mother. “Duh kehn ehr nisht bleiben a Yid, mir darft em shiken in yeshivah —Here, he cannot remain a Yid, we must send him to yeshivah,” he said. His mother started to cry. She wasn’t ready to say goodbye to her Yankele. She wasn’t ready but she did it anyway.

A neighbor of theirs attended Yeshiva Heichal HaTorah in Manhattan, led by Rav Yechiel London, and the Rajchenbachs decided that would be good for Yankele too. And so, they escorted him to the Greyhound bus and off he went, on a grueling 34-hour drive to New York. As soon as the bus pulled away, Yaakov’s father burst into tears. Later, Yaakov would explain that the last time his father had stood beside a roaring engine, bidding farewell to his children, it had been for the last time ever — and he knew it.

It was a sacrifice which, to this day, the family refers to as Akeidas Yitzchak. His parents overcame their emotions, giving up everything for ratzon Hashem, a secret inherited by the children of Avraham Avinu. From his place by the window, Yankele watched and understood.

Years later, when the Rajchenbach children began attending yeshivah out of town, they never left home without their father escorting them to the airport, hugging them tightly and giving them a most heartfelt brachah for hatzlachah. And maybe that’s because he remembered the day when his own parents sent him off to yeshivah for that very first time.

Yaakov did well in Heichal HaTorah; he learned there for a year and a half, until he felt it was time to move on. At the time, Rav Shmuel Feivelsohn, along with Rav Naftoli Hirschfeld, had opened a new yeshivah in St. Louis, Missouri. St Louis was a lot closer to Omaha than New York was, and this served as a strong incentive to join the yeshivah. Yaakov took a farher and was accepted. Thus began his relationship with Rav Shmuel Feivelsohn, whom he would forever call his rebbi.

“Over the course of my life I have met many roshei yeshivah,” Yaakov once said in an interview. “But I have never met a rosh yeshivah like Rav Shmuel, who had such a unique personality and took such a great interest in his talmidim and their lives.”

Yaakov learned in the St. Louis yeshivah for the next two years, and then, when his parents insisted that he get a college education, he enrolled in the Skokie yeshivah, which offered accredited college courses.

In Skokie, he learned under such Torah giants as Rav Yaakov Perlow (the Novominsker Rebbe), Rav Mordechai Rogov, and Rav Aharon Soloveitchik. But aside from a positive yeshivah experience, the move to Skokie proved to be providential in another way. While there, he was introduced to a young woman, a Chicago native, by the name of Judy Klein. They married in 1970, and Yaakov continued on in Skokie — one of the select few to join the yeshivah’s kollel.

But Yaakov’s parents had taught him well. Spiritual growth necessitates sacrifice, and although it wasn’t so popular in those days, the young Rajchenbach couple left America so Yaakov could learn in Eretz Yisrael. There, he enrolled in the semichah program of Machon Harry Fischel, and the couple survived, as best they could, off the kollel’s 650-shekel monthly stipend. But then, an envelope from Yaakov’s parents came in the mail. It contained a check for 100 dollars, and that didn’t make much sense. The senior Rajchenbachs worked as tailors in a department store, the only position that wouldn’t demand that they work on Shabbos. They worked hard but had no money to spare.

The mystery grew with each passing month as the checks continued to come on a regular basis. It was years later that they finally learned the backstory. Apparently, when they made the move to Eretz Yisrael, Yaakov’s parents moved as well — into their unfinished basement. They then rented out the main floor of their home for 100 dollars a month — just enough money to send to their Yaakov and Judy in Eretz Yisrael.

Be My Partner

Had life moved forward on the projected path, Yaakov would have used his semichah certificate to earn himself a position somewhere in the rabbinate. But that wasn’t meant to be. Judy Rajchenbach’s father passed away suddenly and the couple decided that the right thing to do was to move back to Chicago to be with her family.

Yaakov hoped to find a position in chinuch, but the school year was already in progress. Their financial situation was growing desperate and Yaakov said to his wife, “If we’re going to be moser nefesh, we’re moving back to Eretz Yisrael, but if we’re here, I have to make a parnassah.” But moving back to Eretz Yisrael was easier said than done — they didn’t even have the money for tickets.

At the time, a Chicago businessman named Boruch Hollander was working in the healthcare industry, managing various facilities. He granted Yaakov an interview, and quite soon thereafter, a job. The two began working together and, a few years later, partnered in acquiring a facility of their own. So began Yaakov Rajchenbach’s foray into the world of business. There were ups and downs, but ultimately, the Heavens smiled down on Yaakov Rajchenbach. He began to see success, and the heart that wanted so much to help his people now had the means with which to do it.

His close friend and neighbor, Reb Gershon Bassman, who attended the Skokie yeshivah together with him, says Reb Yaakov didn’t just all of a sudden become a public servant. “I don’t think there was any one point in which Yaakov pivoted to become a klal-oriented person,” says Bassman. “Yaakov always cared about the klal — that’s just who he was.”

Although his primary focus was corporate healthcare, over the years, a range of other Rajchenbach-owned enterprises began to crop up across the landscape of corporate America and beyond. This could be seen as a business strategy, bold and creative diversification — but Yaakov once confided to a friend that that wasn’t really the point. “I probably would have made more money had I focused all my energy on my healthcare business,” he said. “But by partnering in all these other businesses, I was able to help so many others make a parnassah.”

As it turns out, building other people’s businesses seemed to be as primary a priority as building his own— if not more. Albert Miller, who is now one of Minneapolis’s most seasoned frum businessmen, recalls how he experienced this personally.

“I was a young man, trying to figure out a way to make a living,” he remembers. “There was a house going into foreclosure, and all I needed was a loan from the bank for 100,000 dollars. I would use that money to purchase the home and then sell it back to the original owner. It seemed like a simple deal, but the bank refused to issue the loan.”

Albert and Yaakov Rajchenbach shared a common relative and had developed a friendly relationship over the years. He called Yaakov for advice. “What you need,” said Yaakov, “is someone with a good signature and a few dollars in his pocket. If you want me to be your partner, I’ll give you a chance.” Albert sent the paperwork to Yaakov’s secretary, who submitted the completed documentation to the bank. “The next day,” Albert says, “the bank called me up and said, ‘Mr. Miller, how much money would you like to borrow?’”

Over the years, this partnership flourished, growing into an impressive portfolio of real estate holdings. Until 2008. Suddenly, a business which held so much potential plummeted, leaving them liable for millions of dollars. One day, an anxious Albert Miller received a phone call from Yaakov Rajchenbach.

“Listen,” Yaakov said. “I’m going to be in Minneapolis, I’m coming over and I need to talk to your wife.”

“He sat down on the couch,” Albert relates, “looked at my wife and said, ‘This is not anything Albert did wrong. This is something bigger than all of us.’ Then he said, ‘We’ll survive this, you’ll be okay, we’ll get through this. Don’t worry, we’ll get through this.’

“It took years,” Albert continues, “but eventually we built ourselves back up. And no matter how hard it got, no matter how much money we were writing out to the bank, Yaakov never raised his voice, never got upset.”

Yaakov founded businesses in multiple cities, and local residents benefited because he believed in them, giving them investment and employment opportunities. And the mosdos of those cities benefitted as well. Yaakov had a policy of supporting the Torah institutions of any city in which he conducted business.

“When the opportunity arose for the Minneapolis Kollel to purchase a new building,” Albert says, “a particular property seemed like the perfect fit. I flew down to Florida where Yaakov was at the time. I described the building, the location, and the price. Right then and there, he agreed to purchase it for the kollel.”

Albert was forever grateful to Yaakov for believing in him and giving him a chance. It was a debt of gratitude he always wanted to repay, but he didn’t know how. So, he asked him straight out: “Yaakov, how can I ever repay you?”

Yaakov looked him in the eye. “If you ever have the opportunity to help build up someone else, do it. That’s how you’ll pay me back.”

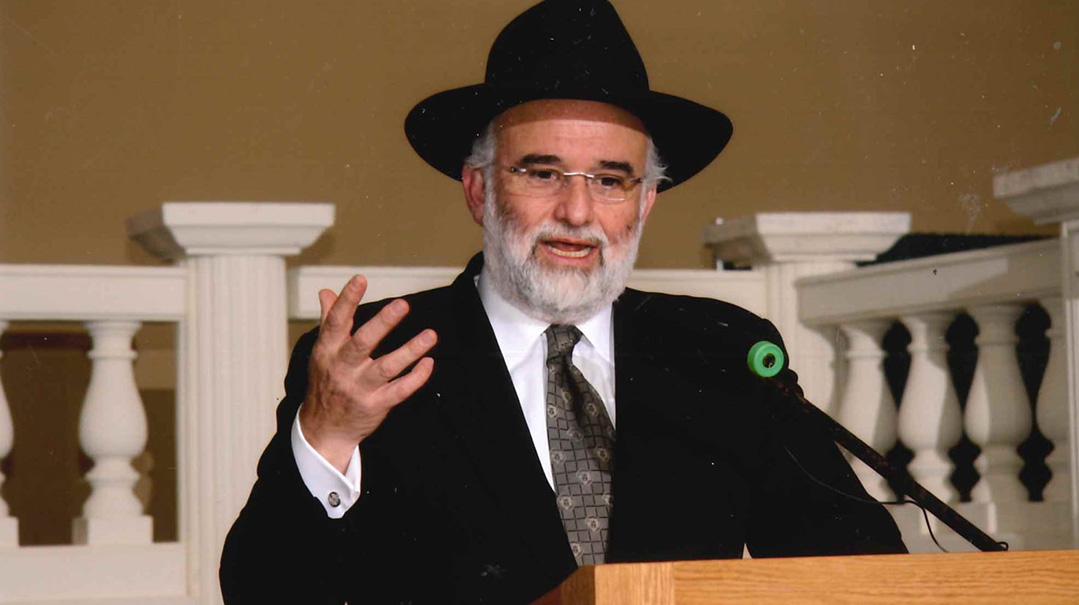

Warm embrace with the Novominsker Rebbe ztz”l

The Numbers Line Up

Albert Miller wasn’t the only recipient of this kind of chesed; numerous others share similar stories. Ari Hollander, a Chicago native who now lives in Florida, relates that whenever he found a deal for Yaakov, Yaakov would insist that he take a significant equity share. “At meetings, he would introduce me as ‘his partner,’” Ari remembers.

But perhaps more incredible than the stories of building businesses for others are the stories of how he allowed others to feed off his own business.

Yaakov once came home after closing on a deal and described to his wife how much was invested and how the various shares were divided. “But Yaakov,” she exclaimed, “the numbers don’t make sense! Based on the amount of money you put in, you’re entitled to much more!”

“Well,” he said patiently, “I have to make a parnassah and the other partner’s family needs parnassah, so it works out.”

The numbers didn’t make sense, but in the world of Yaakov Rajchenbach, even math bends to chesed; as far as he could tell, the numbers lined up perfectly.

And they did, even from the beginning. Many years ago, when Yaakov had just started out in business, money was still scarce, enough for the bank to issue a notification informing him that the account was near empty. Shortly before Pesach there was a knock on the door, and there stood a fellow collecting money. Yaakov wrote out a check which both he and his wife knew would be scraping the very bottom of the barrel. When his wife asked him if the check might bounce, he said, “Listen, I’ll make that money before he does.”

And so, when the money started coming in, it had to accommodate the generosity that sometimes didn’t jive with facts and figures.

Still, over the years, there were instances in which money was wrongfully or unscrupulously taken from him. Yaakov was a humble man, but there was one thing that he took much pride in. “I have never seen the inside of a beis din or a courtroom,” he would tell people. Both his children and his business partners admit that this meant losing millions of dollars, multiple times. But to Yaakov, no money in the world was worth machlokes. He was the quintessential ohev shalom, and was a national destination for mediation in business disputes. Even people struggling with shalom bayis would often turn to him for advice.

His secretary of over 30 years, who was fully involved in all his business affairs and knew, perhaps better than anyone, when Yaakov had reason to be upset, testified that she never once heard him say a bad word about anyone.

It was his dedication to shalom at all costs that steered him from machlokes, but perhaps it was something else as well. “It never seemed like Yaakov viewed money as something that was his,” says Gershon Bassman. “He truly believed that it was given to him by HaKadosh Baruch Hu to distribute to Klal Yisrael.” So why fight over money that really isn’t yours?

Like His Own Pain

A word often associated with Yaakov Rajchenbach is “askan,” but, says his son, the term isn’t entirely accurate. “It wasn’t some kind of plan to involve himself in communal needs,” he tells me. “He just cared about everyone — yachid or rabim — and did what needed to be done to make sure their needs were met.”

In terms of his work for the klal, there isn’t an institution in Chicago that doesn’t have his imprint on it. He served as chairman of the board of the Chicago Community Kollel and the Telshe Yeshiva of Chicago, and was a member of the presidium of the Joan Dachs Bais Yaakov Elementary Hebrew Day School. Both in Chicago and internationally, he provided financial support to an endless list of mosdos as well as advice, guidance, and whatever other assistance he could offer.

And somehow, no matter how heated an issue might be, when Yaakov was involved, everyone left happy – and no one benefited more from his magic touch than did the Chicago community. Like many communities, Chicago went through periods of rapid growth spurts, but somehow, it managed to have those spurts without the growing pains. Because Reb Yaakov made sure that as fast-paced as things went, it never hit turbulence.

But no matter how public a role he’d played, Yaakov never forgot the yachid. His children remember how he would sit for hours on end, schmoozing with teenagers who came by the house looking for chizuk. At the levayah, one son noticed a man crying bitterly, as if he had just lost his own father. It took him a moment to recognize the fellow: Years ago, he had been one of those teenagers, going through a difficult patch and Yaakov had taken him under his wing, treating him like a son.

The man cried because, in a way, he really had lost his father.

Yaakov also became an address for boys struggling in yeshivah, or struggling with Yiddishkeit in general. He would take them on shopping trips, buy them ties or the like — his way of encouraging a youngster who wants to feel proud of his identity but is struggling to find that spark.

Much as he cared for Klal Yisrael wherever they were, he took a special pride in the frum community of Chicago and cared deeply about its continuity. To that end, he invested in building up and nurturing other askanim, making sure that there would be a younger generation to carry the torch when the older generation passed on.

Moshe Davis, who grew up in Chicago and is many years younger than Yaakov, remembers when he got the phone call. “I was already serving on the board of the Joan Dachs Bais Yaakov,” he recalls. “But there was an opening on the presidium and Yaakov pushed me into accepting it. He did this with many people. He was very proud of the fact that Chicago had a succession plan for askanus so that lay leadership would successfully continue.”

For Reb Yaakov, Klal Yisrael’s future wasn’t a subject of facts and statistics; it was absolutely personal. “Yaakov could speak for hours about Klal Yisrael,” Moshe tells me. “He could go on and on about how many classes were born in Lakewood this week, or how much the Chicago community has grown. He was like a grandfather kvelling over his grandchildren.”

Moshe describes how deeply Yaakov felt the needs of his people. “We all talk about the idea that Klal Yisrael is one body, how if one part is hurting, the rest of the body hurts as well. We talk about it but for Yaakov, that was real. He really felt another Yid’s pain, just like it was his own.”

Payback Time

For all the loans he gave out and personal favors he did, it was always about paying forward and not paying back. Rabbi Henoch Plotnik, ram of Yeshivas Kesser Yonah-Chicago, remembers his early days in the Chicago Kollel. “We wanted to buy a house,” he says, “but we couldn’t afford a down payment.” Rabbi Plotnik managed to secure loans from several local balabatim and then approached Yaakov Rajchenbach and requested to borrow a substantial sum. Yaakov pulled out his checkbook but then looked at Rabbi Plotnik sternly. “I am lending you this money on one condition,” he said. “Will you agree to this condition?” Rabbi Plotnik nodded.

“I must be the last person you pay back.”

It was a chesed typical of Yaakov Rajchenbach, but he went on to explain to Rabbi Plotnik that he had an ulterior motive as well. “If you buy a home here, that means you’re hopefully going to settle here. That means you’ll remain in Chicago and be marbitz Torah our city! It’s my greatest kavod to settle the city with bnei Torah.”

If facilitating the spread of limud HaTorah was the greatest kavod for Yaakov Rajchenbach, that’s because Yaakov Rajchenbach had the greatest kavod for Torah.

Rabbi Plotnik once asked him what he did to merit children that were bnei Torah of such a high caliber. “Perhaps because I was mechabed the talmidei chachamim that came to my house,” Yaakov replied simply, “and so Hashem rewarded me with a house full of Torah.”

His kavod haTorah wasn’t a matter of ceremony; it was the compass that guided him throughout his entire life. Yaakov served as the chairman of the board of Telshe Yeshiva of Chicago and, one year at the annual dinner, Yaakov said on a video that before assuming the position, he was told by the former chairman, Reb Aharon Eisenberg, that “the job of the chairman of the board is to carry out the desires and the wishes of the roshei yeshivah.” He was the chairman, but that was merely a title. The opinions he voiced were only those sanctioned by daas Torah.

Yaakov was once invited to join the committee of a prominent national Torah organization. “Any decision I make will be informed by the daas Torah of Rav Elya Svei,” was Yaakov’s response to the invitation. “If you’re okay with having Rav Elya Svei on your committee, I’m happy to join.”

Rabbi Moshe Francis, rosh kollel of the Chicago Community Kollel, recalls how Yaakov lived this message. “Yaakov was from the group who founded the kollel,” says Rabbi Francis. “He was 34 years old at the time, and I was 31. But regardless of the fact that I was so young — younger than he — Yaakov would always say at board meetings, “We have to follow the decision of the roshei kollel.”

For personal questions, Yaakov always turned to his rebbi, Rav Shmuel Feivelsohn, for direction. For questions pertaining to the broader frum community, he would turn to Rav Elya Svei, and after he passed away, to Rav Avrohom Chaim Levin. Seeking the guidance of daas Torah was a value he strongly instilled in his children as well. “If we asked a question to daas Torah and received an answer,” one son recalls, “he wouldn’t even allow us to think about the issue anymore. His attitude was that if that’s what daas Torah says, then that’s what you must do.”

Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky once returned to Philadelphia from a trip to Chicago and told one of the Rajchenbach boys, who was learning in Philadelphia at the time, that “Afilu der housekeeper farshteit (even your housekeeper understands) your parents’ values.” It turns out that after spending some time Chicago, the Philadelphia rosh yeshivah stopped off at the Rajchenbach home to say goodbye before heading back. Rose, the housekeeper, opened the door a crack.

“I’m here to see Mr. and Mrs. Rajchenbach,” Rav Shmuel said.

“Not home,” she said, “Sir is not home.”

“Okay,” said Rav Shmuel. “Please give them a message that a rabbi from their son’s yeshivah sends regards.”

A minute later, the door swung open wide and Rav Shmuel was ushered into the home as trays of food were brought out in his honor.

The Perfect Job

While Yaakov Rajchenbach held gedolei Yisrael in the utmost esteem, they, too, respected Reb Yaakov as an adam gadol in his own right. Rabbi Plotnik remembers a time when a complex community-related issue arose. Having learned in the Philadelphia yeshivah, Rabbi Plotnik called his rebbi, Rav Elya Svei, and presented him with the question. Rav Elya had one question in return: “Vos zugt Rajchenbach? What does Rajchenbach say?”

The regard in which Rav Elya held Yaakov Rajchenbach became evident when, at the Agudah Convention in 1997, he asked Reb Yaakov to meet him in his room on Erev Shabbos. Yaakov entered the room, surprised to find it full of rabbanim and askanim who were involved in Torah Umesorah. Rav Elya looked at him and said, in no uncertain terms: “Reb Yaakov, we decided that you should be the nasi of Torah Umesorah.”

After consulting with Rav Shmuel Feivelsohn, he accepted the position. Serving at the helm of Torah Umesorah was a role that he took much pride in. It wasn’t the honorary title that excited him; for Yaakov, the opportunity to serve as the shaliach of Rav Elya in helping Klal Yisrael develop and grow more Torah mosdos was the chance of a lifetime.

Upon accepting the mantle of leadership, Yaakov delivered a speech in which he shared a story from his childhood. Once, upon returning from yeshivah to Omaha for bein hazmanim, he saw an old man by the name of Mr. Shafer weeping. He asked Mr. Shafer what was wrong, and the elderly man led him to a room in the back of the shul filled with Gemaras. He explained that Rav Hirsch Grodzinski, a great European gaon who served as a rav in Omaha, used to give shiurim there. The fellow pointed to the Gemaras, telling Yaakov with tears rolling down his cheeks, “It’s been years since anyone has learned from these seforim. My own sons all married non-Jews. I thought Klal Yisrael was over. But now, I see a yeshivah bochur, and I know Klal Yisrael will have a kiyum.”

His words sparked an inspiration that would serve as the impetus to build, fund, and facilitate the oversight of hundreds of Jewish schools, providing Jewish education to hundreds of thousands of Jewish children.

As president of Torah Umesorah, Yaakov worked closely with gedolei Yisrael, especially Rav Elya Svei, believing that guidance is the key to a successful school. He saw to it that the plethora of chinuch questions from around the country were addressed by Torah Umesorah’s rabbanim and that the proper hadrachah was being provided. He also strongly believed in professional guidance and was instrumental in establishing Aish Dos, which offers a teacher training program for rebbeim in schools and yeshivos.

It was a job that meant enhancing Torah and Yiddishkeit around the globe. It was the perfect job for Yaakov Rajchenbach.

Ripple Effect

The Rajchenbach home was filled with talmidei chachamim who were afforded the greatest honor, but they weren’t the only ones who were welcome.

“It is typical for baalei tzedakah to implement a system that allows for an organized structure in distributing funds to collectors,” says Rabbi Francis. “But Yaakov Rajchenbach refused to do it. They were always welcome, no matter who they were, and no matter how busy Yaakov was. The streams of people were welcomed inside, treated respectfully, and given a generous donation.”

The Rajchenbach children would answer the door, but they knew better than to say, “Tatty, there’s a meshulach at the door.” Yaakov Rajchenbach despised the word “meshulach.” “Meshulach?” he would say, “a choshuve Yid!”

Someone once pointed out to Yaakov that collectors might actually appreciate it if he would establish set hours. That way, they would know when and where to find him, making their job easier. But Yaakov wouldn’t hear of it. “If I make hours where I’m available, that means there are hours where I’m not available. And I can’t do that.”

“For my father,” one son tells me, “not being available was treif. Tatty would come home from work late and sit down for supper together with my mother, long after the kids had eaten. But he never got through a meal. The doorbell would ring and he’d rush to answer it. And he wouldn’t just hand them a few dollar bills. He would bring each collector in, listen to his story, treating him with utmost respect.”

Only then would he write out a check before turning to the next fellow waiting at the door.

The gush of generosity that poured from the Rajchenbach home had a ripple effect. “Yaakov was one of the balabatim who changed the entire attitude of giving tzedakah in Chicago,” Ari Hollander says. “He didn’t up it a notch, he upped it ten notches.”

People in need of financial assistance came to his home, but for Yaakov, tzedakah wasn’t only at home and it wasn’t only with money. Shortly after his petirah, a sister-in-law of his was in Boro Park for a simchah and entered a store that sells men’s dress shirts. At some point, she mentioned to the store owner that she was related to Yaakov Rajchenbach. The store owner’s eyes lit up. “Yaakov Rajchenbach? Do you know what a special person he was?” He then shared the following story. A few years back, Yaakov had been in Boro Park for a meeting with the Novominsker Rebbe. He was wearing a cufflink shirt which somehow got soiled, so he entered the store in search of a new one. Unfortunately, the store didn’t have a cufflink shirt in his size.

“That’s okay,” said Yaakov, “I’ll take a regular button shirt.”

They rang up the purchase and handed him his receipt but Yaakov wasn’t finished yet. He removed the cufflinks from his old shirt.

“I won’t be wearing these today,” he said, “so why don’t you take them? Give them to someone who looks like he can use them.” With that, Yaakov handed his valuable cufflinks to the store owner and went on his way.

“Sure enough,” the store owner concluded, “a short while later, a chassan entered the store looking to buy a new shirt. I automatically took him to the cufflink section since I assumed that that’s what he wanted. But he shook his head, shyly explaining that his kallah’s family couldn’t afford a watch, certainly not cufflinks. And so I pulled out the set Yaakov had given me and handed it to him. He left with a brand-new cufflink shirt along with a set of cufflinks more beautiful than he ever could have imagined owning.”

How to Defy Death

The Rajchenbach children grew up in a home filled with Torah and chesed, but also with simchah, happiness, and a love of life. “Tzahalaso al panav,” Yaakov’s son said of him at the levayah, “Joy was always on his face.” His appreciation for the blessing of life was so great that it literally defied death. “He was not fighting the machlah,” his wife said, “he just told the machlah to step aside as he continued living a productive life.”

His simchas hachayim informed a fun-loving way of giving, making the lives of others a little more enjoyable.

Every Erev Pesach, Rabbi Plotnik would get a phone call from Yaakov, informing him that the chocolate-covered strawberries were ready and waiting for him.

“These strawberries were enormous,” Rabbi Plotnik says, smiling at the memory. “He ordered them from out of state. Every Erev Pesach he’d melt chocolate, dip in the strawberries and hand them out.” It was a small gesture, a way of easing the Erev Pesach tension just a little bit, making a fellow Jew smile and enjoy a light moment.

“As a father, he was so normal,” his son relates. “I learned in the Philadelphia yeshivah and sometimes he would come by and have a long, intensive meeting with Rav Elya. Then, he’d take me out for pizza as if nothing significant had happened.”

There was no better example of the fun-loving Rajchenbach spirit than on Purim, when their home was dubbed the “Raj Mahal.” Yeshivah bochurim would come in throngs until well after midnight, a rav would come to share divrei Torah, and a professional chef was hired to provide the finest cuisine. But Rabbi Plotnik explains that it wasn’t just about having fun. “Purim was a problem in Chicago for a long time,” he says. “Bochurim came from all over to collect, they would be roaming the streets with no real destination, leading to all sorts of potential for trouble. The Rajchenbachs instituted an annual Purim celebration as a way of solving this issue. Bochurim coming to Chicago all knew that a warm welcome, and deluxe seudah, awaited them at the Rajchenbach home.”

A Mop and a Pail

Over the years, Chicago’s frum community grew, and Reb Yaakov took enormous pride in every step of that growth. But what was likely his greatest pride and joy was the Chicago Community Kollel. Yaakov had been involved since its inception in 1981. He and a few friends had gone down to Lakewood to meet the potential roshei kollel, and then to Monsey to consult with Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky on various issues pertaining to the kollel’s establishment.

Rabbi Moshe Francis shares a memory from those days. It’s a short story, but it’s the whole story.

After a flurry of rapid arrangements, the kollel — which was to be located in the basement of Rabbi Small’s shul in West Rogers Park — was finally ready to begin. The night before the first day of the zeman, Rabbi Francis went together with Reb Yaakov to check out the premises and make sure it was ready to go. Together, they went down to the basement, observing the small room that would one day transform a city. Suddenly, Yaakov grabbed a mop and a pail and proceeded to mop the floors.

“I never forgot that,” says Rabbi Francis. “Sometimes, when I think about all that Yaakov Rajchenbach was zocheh to, I think back to that mop and pail.”

It seems like a jarring paradox.

Yaakov Rajchenbach, leading figure in the healthcare industry, founder of so many companies, sought-after patron of institutions worldwide.

Yaakov Rajchenbach, the fellow bent over a basement floor scrubbing it clean with his own hands.

But it’s not a paradox at all.

At the levayah, one of his sons quoted the Gemara in Berachos (34b) of how Rabi Chanina ben Dosa davened for the sickly son of Rabi Yochanan ben Zakai, and the child had a miraculous recovery. Rabi Yochanan ben Zakai commented that even if he would have davened all day, he could not have merited such a Divine response. “V’chi Chanina gadol mimcha?” His wife asked. “Is Rabi Chanina greater than you? Why are his tefillos so much more effective than yours?” “No,” responded Rabi Yochanan ben Zakai, “elah hu domeh k’eved lifnei hamelech va’ani domeh k’sar lifnei hamelech — He is compared to a servant before the king, and I am like a prince before the king.” A servant is granted the informal liberty to appear before the king in a way that a prince, bound to the formalities of the palace, cannot.

Some are princes and some are servants. And some are both.

Throughout the corporate world Mr. Jack Rajchenbach carried himself as the dignified representative of a most royal calling. And in a basement of a shul in Chicago, Yaakov Rajchenbach mopped the floors in preparation for the next day’s seder.

The Gemara in Chagiga (3a) refers to Avraham Avinu as a “nediv” — a nobleman, a prince. Yet a pasuk in Bereishis (26:24) explicitly refers to him as servant (“ba’avur Avraham avdi”).

Because some people are both. To be a prince while being a servant is a synthesis mastered by Avraham Avinu, which he then taught to the world.

And Yaakov Rajchenbach learned it well.

This past Tishah B’av, the Chicago community bid farewell to the man who gave his entire self for their success, wellbeing, and future. Reb Yaakov was afraid of this day — he knew how much he had given, and how much the community depended on him. But just as Avraham Avinu received a direct reassurance from Hashem — “Al tirah Avraham, Anochi magen lach, scharcha harbei me’od (Fear not Avraham, I will protect you, your reward is very great)” — it became clear during the weeks following his passing that he, too, had nothing to fear. As his children, family and beloved friends escorted him on his final journey — an army of princes, an army of servants — one could almost hear the Heavenly call: “Fear not, Reb Yaakov, fear not. Scharcha harbei me’od.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 929)

Oops! We could not locate your form.