A Head of His Time: The Life and Legacy of the Meitscheter Illui, Rav Shlomo Polachek

Today, it is clear that his faith in America’s fledging yeshivah world bore generations of blessed fruits

Photos: Yeshivah University Archives, Torah Vodaath Archives, YIVO. Rabbi Dovid Kamenetsky, Gordon Family, DMS Yeshivah Archives, Feivel Schneider, Feldheim Publishers, US Library of Congress, NYPL Yizkor Book Collection, Friedman Family and Rabbi Dr. Aaron Rakeffet Rothkoff

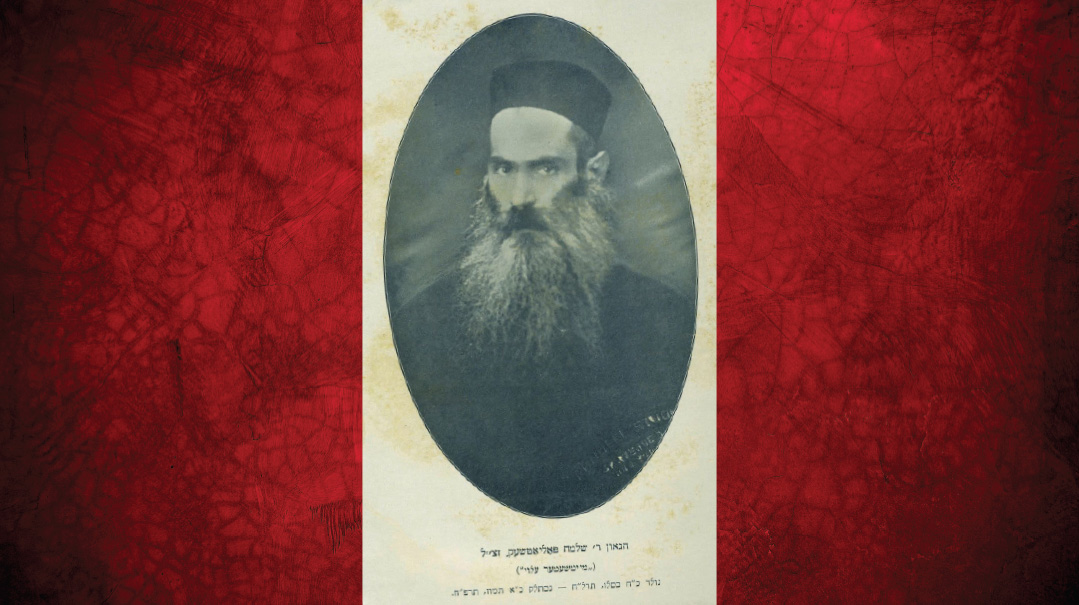

IN Jerusalem's Kiryat Moshe neighborhood there’s a street with an unusual name: Rechov Ha-Illui — Street of the Genius. Illui is a rather modern term dating back to the last 200 years or so. The Rambam and Rashi were never referred to as illuyim; the term seems to have become popular only with the advent of the European yeshivah world. Fittingly, the street sign in Kiryat Moshe refers to one of its most exemplary and fascinating figures: Rav Shlomo Polachek, the Meitscheter Illui.

The odd name choice on the street sign — not Rechov Rav Shlomo Polachek or Rechov Ha-Illui -Mi’Meitschet — is unique and telling. As a student in the vaunted Volozhin yeshivah, as a prized student of Rav Chaim Brisker, and as a sought-after rosh yeshivah on two continents, Rav Shlomo Polachek was known as the Illui, the ultimate genius. His prodigious mind was so unusual that Rav Elchonon Wasserman wrote that he personally heard Rav Chaim say, “Aza meshunidike illui vi der Meitscheter hab ich in leben nit gezen — in all my life I’ve never met such an extraordinary genius as the Meitscheter.”

But perhaps his lasting legacy lies with the most consequential step he ever took, when he made the decision 100 years ago to accept a position as rosh yeshivah in America’s first institute of higher Torah study, Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon (RIETS).

Unlike so many of his European counterparts, Rav Shlomo Polachek believed that American bochurim were capable of high-level Gemara learning and that the forbidding American soil could bring forth a harvest of authentic Torah scholarship.

Back then, many viewed the Illui’s move as just another inscrutable step taken by a staggering genius whose mind spun faster than they could fathom. Today, it is clear that his faith in America’s fledging yeshivah world bore generations of blessed fruits.

Part I: A Prodigy Comes to Volozhin

Where Is the Boy’s Crib?

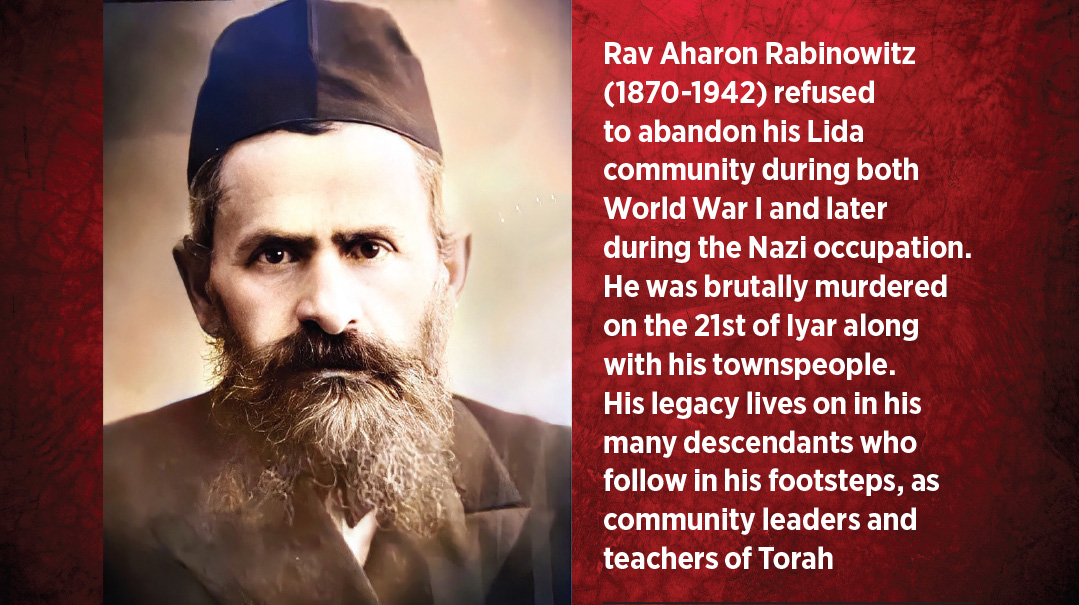

It was 1889, and Aharon Rabinowitz, a promising young student in the famed yeshivah of Volozhin, had returned home to the city of Haradzets for Yom Tov. He would later become the last rav of Lida and gain renown for his piety and devotion, even earning the title of “Ish Emes — man of truth,” from the Chofetz Chaim. But he is likely remembered most for an encounter that took place that Succos.

It was no surprise to him when a visitor arrived at his home along with a young boy. The boy’s uncle, Rav Shmuel Meir Horowitz, had been telling Aharon Rabinowitz about him for some time. The man introduced himself as Reb Yosef Polachek and explained that he’d traveled from the small village of Sintzenitch, adjacent to the Grodno province of Meitschet (widely pronounced “may-chet), where he made a living operating an inn as well as the adjoining post office in his remote village. His son Shlomo, he told Aharon, had been born there in 1877 and orphaned of his mother Resha a short time thereafter.

When Reb Yosef hired a tutor to teach his older children Chumash, he began to notice that three-year-old Shlomo would sit under the table quietly and answer all of the questions intended for the older ones. Very soon, it became clear that he was no typical child.

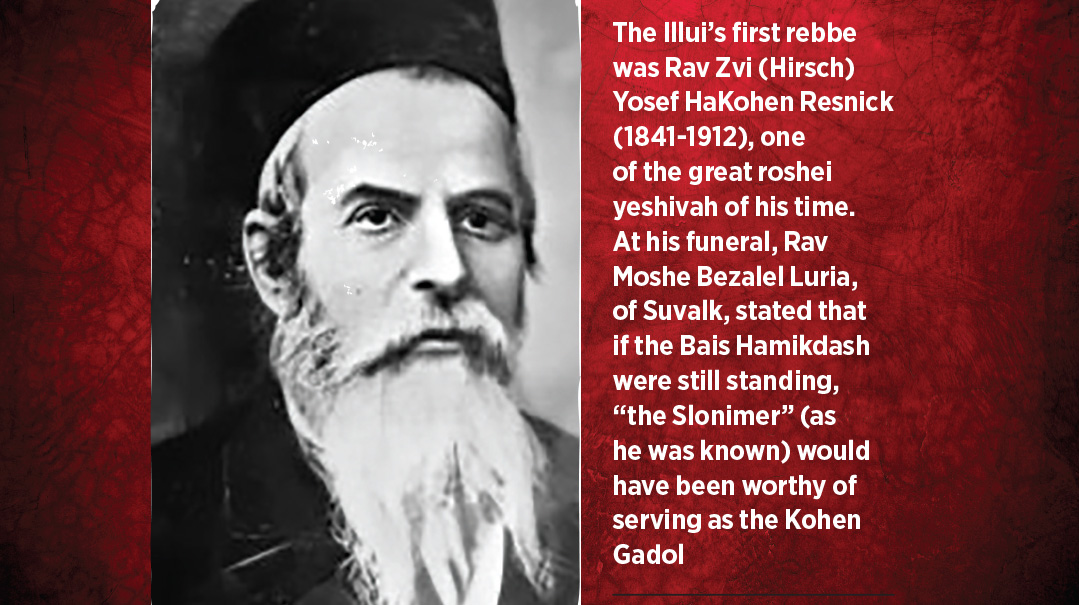

At six he commenced learning Gemara in the nearby Meitschet cheder, and at eight he was sent to a preparatory yeshivah in Novardok, then to the yeshivah of Rav Tzvi Hirsch Resnick in Slonim, where he was quickly promoted to the highest shiur. The older students grew jealous and mistreated the neophyte, yet the slight and bashful Shlomo did his best to ignore their taunts and used the three years he spent at those yeshivos to grow further in his studies.

Now the young boy stood uncomfortably in the doorway, averting his piercing dark eyes from Aharon Rabinowitz’s gaze as his father continued to sing his praises. “He just turned 12, so it’s hard to imagine, but he grasps even the more difficult sugyos without the aid of a teacher. He can easily follow the most difficult reasoning, down to the finest details. I would be greatly appreciative if you could take him to the one place they say a mind like his can grow further: the Volozhin yeshivah.”

Aharon Horeditcher, as he was known in Volozhin, began to speak to the young boy and quickly realized that his father was not exaggerating. Shlomo was thin, weak, and shy, but his eyes radiated wisdom and understanding beyond his years. And when Aharon tested the child’s Torah knowledge, he was dumbstruck by his ability to explain a complex svara in just a few words.

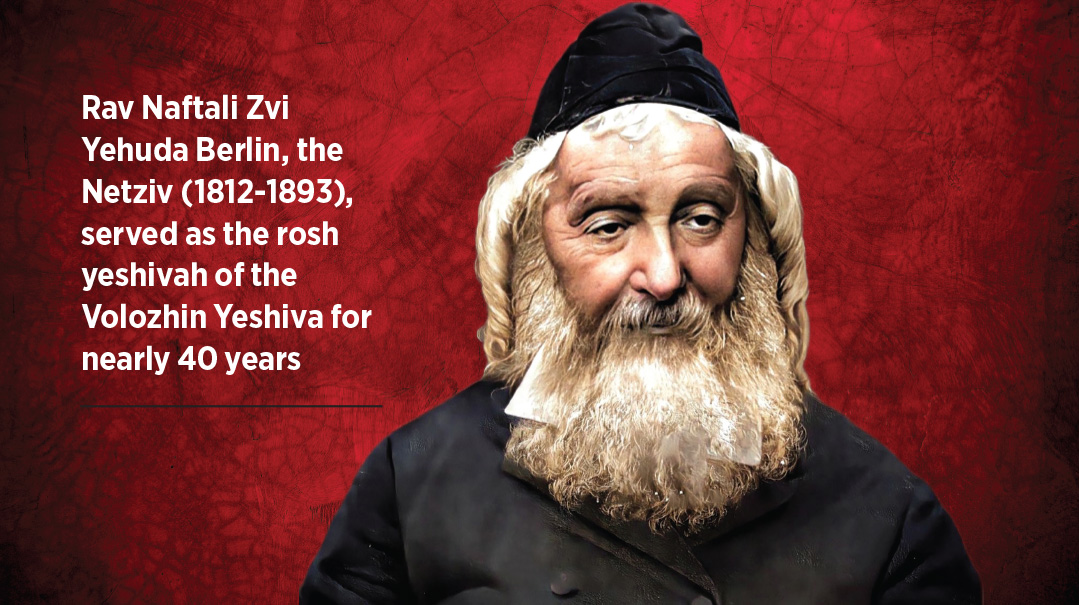

A few days later, he took young Shlomo Polachek back with him to Volozhin, sneaking him in under his coat into the yeshivah building, where they proceeded directly to the office of Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, the Netziv, who was then serving in his 35th year as Rosh Yeshivah. The scene was witnessed by a fellow student named Eliyahu Gordon, who later shared what happened.

Surprised at the sight of the 12-year-old (who looked much younger), the Netziv quipped, “Why didn’t you bring his crib along?”

Aharon Horeditcher shot back, “Why don’t you test him and decide what size crib he needs?”

Out of respect for his esteemed student, the Netziv agreed and immediately posed a difficult question to young Shlomo and told him to go into the next room to think it over. The boy went toward the door and turned back — he already knew the answer. The Netziv posed another, more difficult question and once again was astounded as he received an answer seconds later. The Netziv tried over and over to stump the young boy but failed.

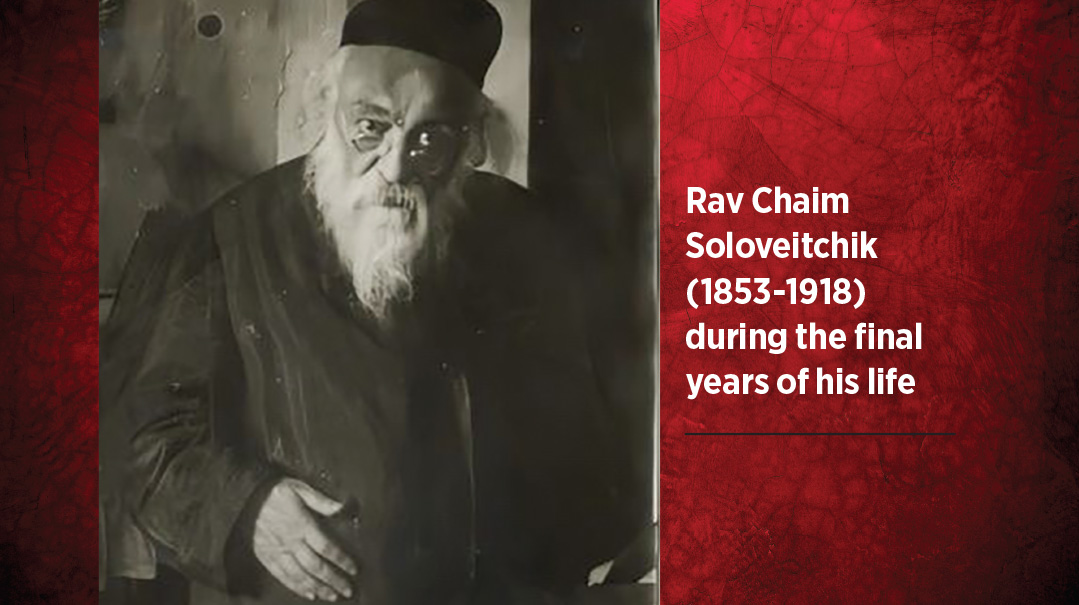

Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, the assistant rosh yeshivah at the time, walked in during the farher and was immediately taken by the young boy’s erudition. When the exchange was complete, he asked Shlomo where he was from.

“Meitschet,” he shyly answered.

“Then we will call you the Meitscheter Illui,” Rav Chaim replied.

That moniker would stick for life.

Backward and Forward

In Volozhin there was a strict hierarchy when it came to titles granted by the hanhalah. Titles were used sparingly, and false honorifics were seldom bestowed in the rigid aristocracy prevalent among both the hanhalah and talmidim. One earned his title through diligence, assertiveness and intellectual prowess. Most didn’t get any illui title, some were known as a halbe illui — half illui, and a select few got the full illui title.

How rare was it for a 12-year-old to be accepted into the Volozhin yeshivah? There are certainly a few instances of young prodigies coming to Volozhin. The future rav of Lodz, Rav Eliyahu Chaim Meisel, arrived in Volozhin at the age of eight; Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, the Bais Halevi, at ten; and Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin at 11. Yet all those incidents occurred during the first half the 19th century, when many Jewish parents in the upper echelons of society were accustomed to marrying off their sons around the age of 13 for various reasons.

Over the years the average age for both marriage and entry into Volozhin rose, and although there were some isolated instances of young boys joining the yeshivah (Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer was one), by the end of the century the arrival of Shlomo Polachek at the age of 12 aroused considerable attention.

Even talmidim in their mid-teens were considered young in Volozhin during those days and rarely were spoken or paid attention to. Yet aptitude was valued more than age, so 12-year-old Shlomo Polachek immediately began to garner the attention of even the most seasoned Volozhin scholars.

Despite the difference in age and position between them, there was a natural bond that quickly formed between Rav Chaim Soloveitchik and his young charge. The Soloveitchik family had a longstanding affinity for great geniuses, and the Illui’s humble nature caused Rav Chaim to admire him even more. When a Torah discussion delved into a deep matter, Rav Chaim would always turn to him with special affection, asking, “Nu, Shloimke, what do you say?”

The Meitscheter would respond almost inaudibly, very briefly, as if he were saying nothing significant, but his response would overwhelm everyone, including Rav Chaim, with its swiftness and lucidity.

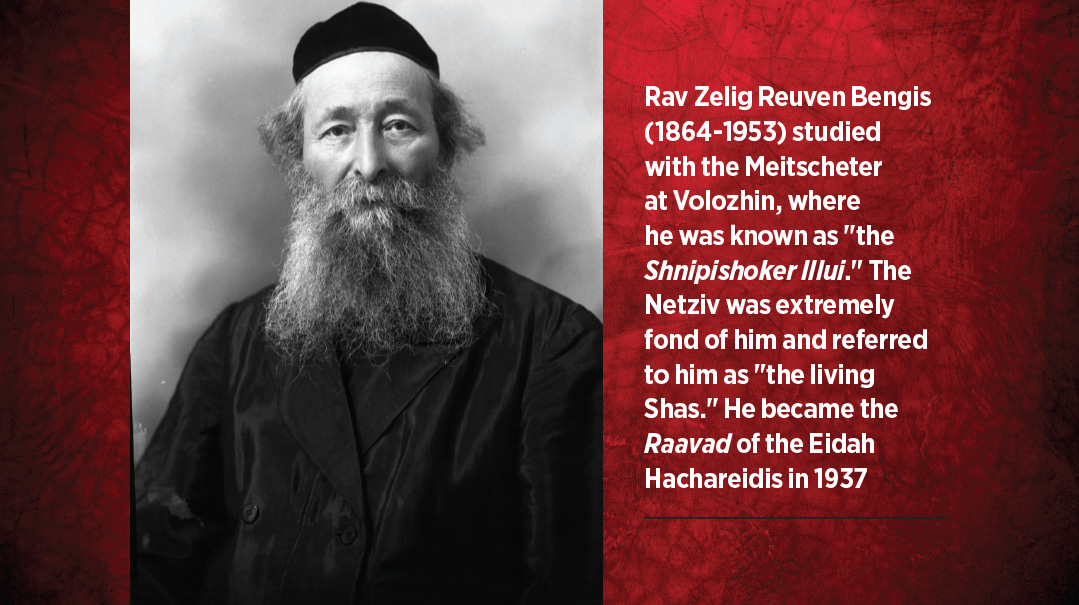

To stand out as a genius in a yeshivah filled with the greatest minds of the era was quite a feat. A classic story about Rav Zelig Reuven Bengis, later to become raavad of the Eidah Chareidis, illustrates the intellectual level of Volozhin’s elite students. Several years before the arrival of Rav Shlomo Polachek in Volozhin, a Czarist government inspector arrived to check whether the yeshivah was fulfilling its obligations to include general subjects within its curriculum. The Netziv called in “a typical student,” Zelig Reuven Bengis, to recite a poem by the famed Russian author Alexander Pushkin.

After reciting the poem flawlessly, Rav Bengis decided to impress the inspector by reciting the poem backward. Very quickly, the inspector realized that this young man was not the typical student he was claimed to be. (In an addendum shared by Rav Berel Kreuser, Rav Bengis allegedly didn’t know how to read Russian and had asked another student to read him a page in a Russian book. He committed it to memory and pretended he was reading from the book when tested by the inspector.)

Around the Clock in Volozhin

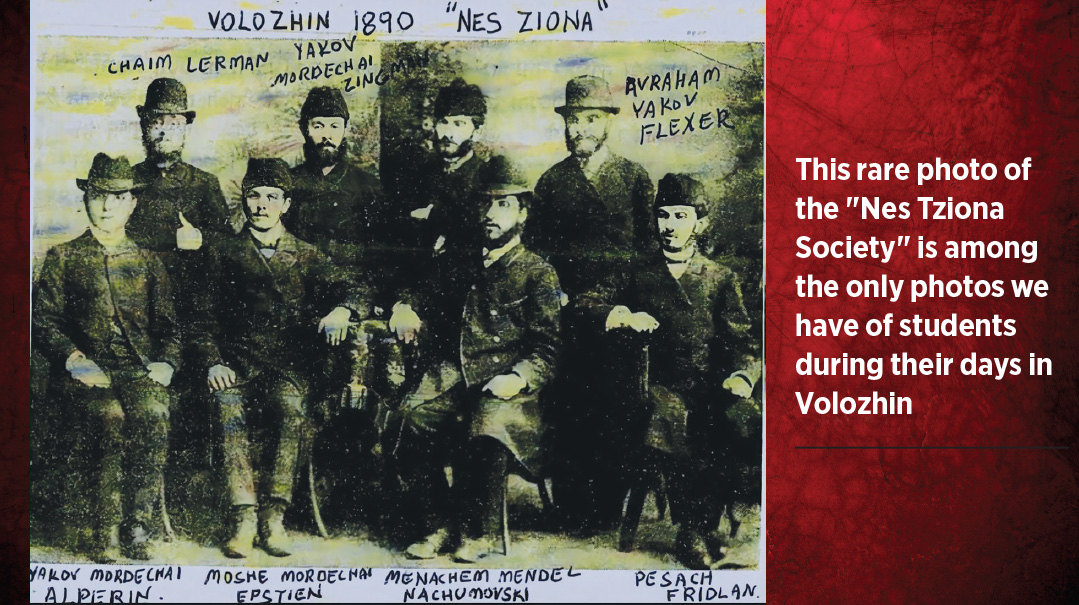

Despite growing financial and political woes, the Volozhin yeshivah was experiencing a golden age at the time of the Meitscheter’s arrival. The yeshivah had its own brick building, and with over 300 talmidim was running at full capacity.

In Volozhin the learning cycle wasn’t limited to specific “yeshivish masechtos,” as is customary in today’s yeshivos. The entirety of Shas was studied, beginning with Berachos and ending with Niddah. The learning was relatively fast-paced, and a daily shiur was delivered between 12 and two p.m., though attendance wasn’t mandatory. During the Meitscheter’s time at Volozhin, the Netziv delivered the shiur on Sunday through Tuesday, and Rav Chaim Brisker did so on Wednesday through Friday.

While Rav Chaim’s shiurim were a tremendous attraction, married talmidim and some of the senior bochurim appreciated the Netziv’s classic approach, and some attended both shiurim.

In his memoirs, Volozhin student Yehoshua Leib Radus recalled how Rav Chaim’s innovative analytical style of learning electrified the young minds of Volozhin: “He jumped from place to place and raced through the daf Gemara at great speed, like someone reciting Ashrei. He demonstrated his prowess through his pilpul, which he would deliver at every shiur. The yeshivah students saw his sharp-wittedness and genius in his pilpul, which astonished those who heard it.”

The excitement generated by Rav Chaim’s talmidim didn’t extend to the study of Kodshim. When the yeshivah seder halimud arrived at Kodshim, the students complained that it was too difficult and should be skipped. In deference to the talmidim’s needs, the primary shiur in the morning skipped Kodshim and commenced the cycle once again with Berachos.

The Netziv insisted, however, that the yeshivah tradition be upheld — with not a single mesechta to be skipped — and he and Rav Chaim delivered optional shiurim on Kodshim in the evenings.

Unlike in the later, more mussar-oriented yeshivos, davening was fairly quick, to allow the students more time to learn. Even on Yom Kippur, there was time for a three-hour learning session. Following Shacharis, the Netziv delivered a daily Chumash shiur, which material served as the basis of his classic work Ha’amek Davar.

The yeshivah’s daily schedule was notable in that it operated 24/7, following a unique daily schedule in the hallowed tradition of Rav Chaim Volozhiner.

From 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., all were expected to be in the beis medrash for the standard yeshivah learning sedorim. The remainder of the day (and night) was divided into three shifts (called mishmarim) of equal length, ensuring that the sound of Torah study was constantly heard within the walls of the yeshivah. All talmidim participated in at least one mandatory three-hour shift between 9 p.m. and 9 a.m.

On Friday nights, half the yeshivah would eat their Shabbos seudah at midnight when their shift was over, and the ones who had eaten and slept would arise at that time to learn until morning. Even on Seder night (most students could not afford to travel home for Pesach), the mishmarim continued.

Remarkably, even as he approached the age of 75, the Netziv never missed a visit to the beis medrash during every one of the shifts each night. Memoirs written by talmidim recall how the beloved rosh yeshivah would pace among the benches, inspecting the talmidim’s progress, talking in learning with some, and inspiring all with his very presence.

Rav Shalom Schwardron conveyed the energy and purity of the Netziv by sharing as story he heard from the Brisker Rav. One Succos, a dispute arose regarding the validity of a certain esrog that had arrived from Eretz Yisrael following the shemittah year, and Rav Chaim therefore passed on his usual custom of blessing the Netziv’s esrog.

The Netziv spent that entire night in his succah, toiling over the sugya in an effort to alleviate Rav Chaim’s doubts. At three or four o’clock in the morning, he found a satisfactory solution and sent for his grandson. A few minutes later Rav Chaim arrived with his entire family, unsure what to expect.

When he saw nothing was awry — the Netziv was sitting in good health surrounded by a large pile of seforim — he quickly excused himself to recite birchos haTorah. Uncharacteristically, the Netziv sighed audibly. Sensing something was amiss, Rav Chaim asked if he had done something wrong.

Choking back tears, the Netziv asked, “Have I sinned in my old age? How could it be that my grandson, the person expected to lead the next generation of Torah scholars, is not awake with a sefer at his table at this ‘morning’ hour? What will the next generation look like?”

The Bar Mitzvah Boy Is Crying

It was this elite milieu in which young Shlomo Polachek found himself upon his arrival in Volozhin in 1889. Rav Chaim established a learning program for the 12-year-old for which he would learn ten blatt a day and be tested each night by Rav Aharon Rabinowitz. Then, every Friday night Rav Chaim tested him for several hours on everything he had learned that week.

It quickly grew clear that his genius wasn’t limited to his astounding breadth of knowledge. It also comprised a deep understanding and tremendous powers of reasoning, which is of course why he was such a good fit for Rav Chaim.

The Illui was the only student known to have had his bar mitzvah celebration take place in the yeshivah. In the days leading up to the celebration, he approached Rav Chaim and asked his advice regarding a pshetl. Rav Chaim opened a Gemara Bava Kamma and told him to ask a question, which Rav Chaim then instructed him to construct a solution for. Rav Chaim then challenged his solution, and the Illui quickly responded. This kept going for an hour, until Rav Chaim said, “Shlomkeh, go think it over, you have a pshetl.”

The bar mitzvah seudah was held in the Netziv’s home, and the depth of the Illui’s pshetel left everyone impressed. Rav Chaim declared, “Shlomo, ich hob oichet ah terutz oif dem Rambam, nor mir gefelt az dein peshat iz besser fun mein — Shlomo, I also have an answer to the shitah of the Rambam, but I like your pshat better than mine!”

The Netziv was floored and asked who wrote the pshetl, and was told that it was the child’s own composition. At first, he didn’t believe it, until Rav Chaim got up and announced he was bearing witness that not only was it all the Illui’s own erudition, he had completely dismantled Rav Chaim’s own theory.

Witnesses recall how the Netziv gave young Shlomo a fatherly kiss on the forehead, followed by a resounding proclamation from Rav Chaim, “A new gadol b’Yisrael is emerging here.”

But all the attention caused the Illui to become exceedingly uncomfortable and he soon began to cry. Rav Chaim comforted him and told him that he too had cried at his bar mitzvah.

Rav Chaim Tzvi Rubinstein (later rosh yeshivah of HTC in Chicago) related to his grandson Rabbi Berel Wein that during his years in Volozhin, the Meitscheter studied for 16 hours a day, but because of his intellectual prowess, nobody could last more than two hours as his chavrusa. So he had eight different chavrusas a day. Rav Rubinstein studied with him from 11 p.m. until one a.m. and was only able to “hang on” because the Meitscheter was tired by then.

Vos Zogt Shlomo?

One of the future gedolei Yisrael who studied alongside the Illui in Volozhin was Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer. More than 60 years later, he used highly praiseworthy terms when describing the Illui to Rabbi Mordechai Shapiro of Miami, the son of the Meitscheter’s dear student Rabbi Yosef Shapiro.

Rav Isser Zalman was about 20 years old when the 12-year-old Illui arrived in Volozhin. The age gap did not prevent the yeshivah’s senior students from seeking him out. “Whenever someone had a question on the Rambam, or a difficult Gemara that they couldn’t understand,” Rav Isser Zalman remembered, “they would say, ‘Nu, vos zogt Shlomo — what does Shlomo say?’”

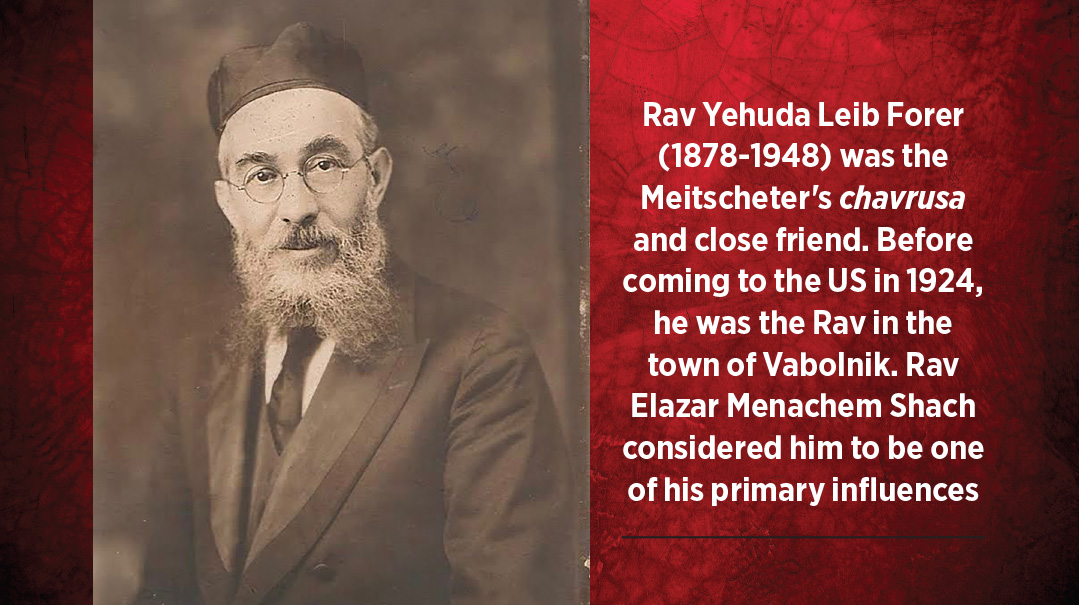

It wasn’t just his fellow students who relied upon the young genius. When Rav Yehuda Leib Forer — later the rabbi of Holyoke, Massachusetts — arrived in Volozhin, he struggled at first to understand all the excitement over the Illui. It didn’t take him too long to discover what the hype was about.

On one occasion when Rav Chaim was delivering a shiur in Bava Kamma, he expressed doubt regarding a certain complex point. “We could find no conclusive evidence to settle the question,” Rabbi Forer writes, “and the exhausted Meitscheter was dozing off. Rav Chaim called, ‘And what do you say, Shlomele?’”

The Meitscheter immediately offered an ingenious, complex answer that settled the question tidily. “And then,” writes Rav Forer, “I recognized his worth and began treating him with deference.”

His acuity in learning wasn’t the only area where the Illui followed in the footsteps of his great rebbi, Rav Chaim. He also mirrored Rav Chaim’s gentleness, purity, and elevated character traits. His selfless concern for fellow students was another reason for his popularity. After a visit back home, he brought back several shirts to yeshivah, which he quickly gave away to friends needier than himself. The shirt he wore was often tattered, but it was clear to those around him that he did not even realize.

The End of An Era

The 1880s were a dynamic time for the Jews of Russia. The assassination of Czar Alexander II, pogroms in the southern districts of the empire, dire economic conditions, and the commencement of the Great Immigration to America all threw the future of the world’s largest Jewish community into question. Russia’s more than five million Jews no longer saw emancipation as a realistic hope, and with no realistic exit from the Pale of Settlement for the overwhelming majority, new ideas and utopian solutions captured the minds of the Jewish street.

This was especially true among Jewish youth, who were becoming increasingly radicalized. Socialism, communism and Jewish nationalism were attracting more and more adherents, as each movement claimed to hold the solution to the grinding challenges of life under Czarist imperial rule.

Yeshivah students were especially susceptible to being swept into the cauldron of passionate notions and movements, and many of these great minds were diverted toward various “isms.” The final years of the Volozhin yeshivah’s existence were punctured by open struggles between various factions of maskilim among the student body and the yeshivah’s hanhalah. Various revolutionary ideologies succeeded to gain footholds in the yeshivah world, as illustrated by this episode:

Rav Eliezer Gordon regularly visited an old friend who had become an influential Bundist in order to solicit funds for the Telz Yeshivah. Once, while Rav Gordon visited him, a friend arrived and began to chastise the Bundist. “Why would you contribute your hard-earned money to such a “backward institution?”

After depositing a large sum of money in the hands of Rav Leizer Telzer, the fellow smiled and replied to his friend with glee. “Yeshivos are important. If not for them, where would we develop our next (Bundist) leaders?”

A confluence of factors led to the unfortunate closure of the legendary Volozhin yeshivah in the winter of 1892. Ever wary of the revolutionaries so prevalent among intelligent and radicalized youth, the Czarist police had their eyes on Volozhin and filed regular reports regarding the goings-on therein.

During this period, the aging Netziv sought to appoint a successor who could restore fiscal stability to a yeshivah facing staggering debt. His attempt at appointing his son Rav Chaim Berlin was seen by some talmidim as an affront to Rav Chaim Brisker. The ensuing dispute and resulting instability caught the attention of the authorities, who interpreted the unrest as rebellious fervor. Leery of any anti-establishment activity, the authorities resolved to shut down the storied institution.

As a pretext, they delivered an ultimatum to the Netziv: The yeshivah schedule was to be limited to nine hours a day, with six of those to be devoted to general subjects and no more than three hours allowed for Torah study. All Talmud teachers had to be certified by the Russian Ministry of Education.

These draconian measures were nothing less than a death sentence for the yeshivah’s functioning, and the Netziv chose to ignore them. The reaction was swift and harsh. Czarist police forcibly shut down the yeshivah and sealed its doors. The talmidim were exiled from the town, and the Netziv, his son, and Rav Chaim Brisker were banned from residing in the entire Vilna district for three years.

The Torah world was thrust into mourning. The great Torah citadel of Volozhin was shuttered. The light that had illuminated the darkness across the Pale was snuffed out.

Among the talmidim dispersed with the closing of the yeshivah was Shlomo Polachek. The budding talmid chacham weighed his options. An uncertain future lay ahead.

Part II: In Search of a Haven

The Apple of Rav Chaim’s Eye

Like many other students, the Illui journeyed from Volozhin to Minsk, where he spent a short time studying in local shuls. With the barriers erected by the yeshivah’s hanhalah no longer in place, the local maskilim pounced on the displaced bochurim. Some of the best and brightest among the city’s youth were ensnared.

When describing this trying period, the Illui later recalled how hurt he had been when, in an effort to weed out irreligious elements among the students, he was asked by the rav in a Minsk shul to display his tzitzis. Such was the level of suspicion and fear in the city.

As the Illui pondered his next move, relief soon came in its grandest form.

While the Netziv traveled across Europe in an attempt to raise funds to pay back the yeshivah’s myriad debts, Rav Chaim had moved to Brisk where his father, the Beis Halevi, was rav. A few months later, on the 4th of Iyar, the Beis Halevi suffered a stroke and passed away. Rav Chaim was immediately declared his successor.

One of his first initiatives was to invite a cadre of his prized students from Volozhin to join him in Brisk. Eager to resume their studies with their great teacher, they gathered in the Mishmar Kloisz on Shpitalna Street and formed the first “Brisker Chaburah.” Among that initial group was the apple of Rav Chaim’s eye — 15-year-old Shlomo Polachek.

Whenever a great Torah scholar visited Brisk, Rav Chaim would seek to introduce the Meitscheter to him and draw him into a Torah discussion in order to display the sheer Torah greatness of his prized disciple. With his natural humility and unusual modesty, the Meitscheter always sought to avoid those occasions. He was physically unable to bear it when he became the focus of other people’s attention.

Once, when Rav Chaim’s close friend and former chavrusa, Rav Itzele Ponevezher, arrived to spend a day in Brisk, the Meitscheter was nowhere to be found. Rav Chaim sent his son Rav Moshe — who was the Illui’s chavrusa — to find him, but he was nowhere to be found. When Rav Itzele finally departed, the Illui returned from his “hideout.” When someone asked him why he had been hiding, he replied, “That Rav Itzele knows how to learn, I know. Whether I do or don’t is not his concern!”

The young Illui did his utmost to not just understand and defend others, but to treat them with deference. When one of his peers made an incorrect Torah statement, he sought to rectify the other person’s error, straining to find some merit in it. He did once criticize a certain person’s opinion in Rav Chaim’s presence, and Rav Chaim said to him half-jokingly that this showed that he lacked trust in our sages. To this the Meitscheter replied quietly and calmly, “Chas v’chalilah! I surely do have faith in our sages. I just don’t believe that that man is a sage!”

The future American Torah leader Rav Eliezer Silver was another one of Rav Chaim’s students in Brisk. He related how Rav Chaim would dictate his chiddushim to the Illui — because he was the only one who grasped the full profundity of his teachings. The Illui would then write them down and Rav Chaim would later review them. Sometimes this process would be repeated as many as four times to ensure the work was up to Rav Chaim’s rigorous standards.

(When Rav Chaim’s son Rav Moshe Soloveichik first printed his father’s chiddushim posthumously in 1936 — a project which both the Meitscheter and Rav Leizer Silver spent years encouraging and raising funds for — he stated in the preface that his father wrote it with extreme precision, having “sifted the text seven times over and winnowed it a hundred times more.”)

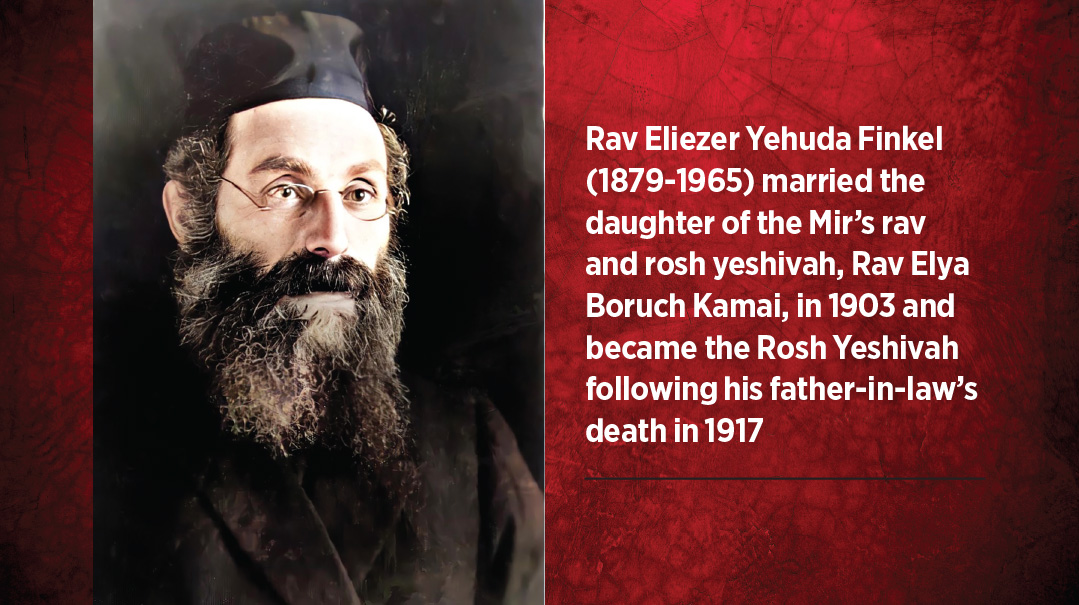

The Mussar Mismatch

In 1896, the Illui was recruited by his fellow student and close friend, Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel, to join his father, the Alter of Slabodka’s yeshivah. Rav Leizer Yudel later recounted how the Alter — who put much energy into recruiting the great Torah minds of the time — heard about the Illui’s reputation and coveted him such that that he sent his son on an “undercover mission” to study in Brisk for the purpose of bringing him to Slabodka.

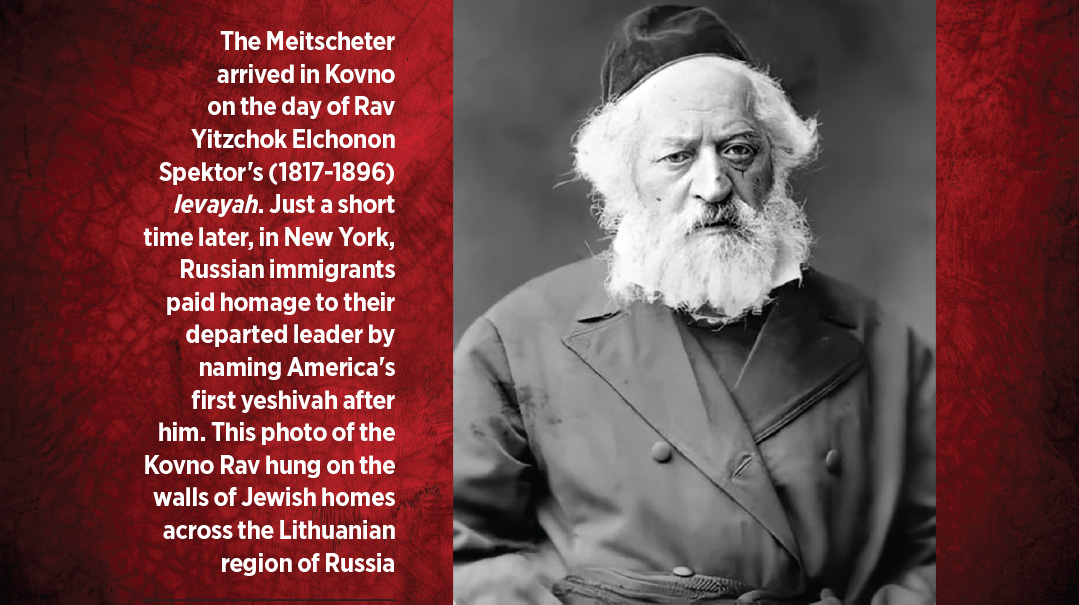

Rav Leizer Yudel succeeded in his mission and convinced the Illui to travel with him to Slabodka, arriving in the neighboring city of Kovno on the 21st of Adar, 1896, the same day of the passing of the gadol hador, Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor. (This author speculates that perhaps the reason the Illui agreed to leave Brisk was because a few months earlier, a fire had destroyed much of the town and he felt the locals could no longer sustain the chaburah.)

The honor that the young Illui received in Slabodka from both the Alter and his fellow students knew no bounds, but this offered little solace to the Illui, who longed to return to Brisk. The Illui was a “baal mussar” in a literal sense, and his morality was expressed in his actions, humility, and in his magnanimous treatment of others — yet he never took to the regular study of mussar texts, nor did he often participate in the shmuessen. This behavior was also likely due to the influence of Rav Chaim, who opposed the organized study of mussar in yeshivos.

Sensing that the Illui needed a change of scenery, the Alter suggested that the Meitscheter join a group of Slabodka talmidim who were spending Elul at the Talmud Torah in Kelm, where the Alter of Kelm was in his final years. Perhaps the more individualized approach there would speak to him. But just as in Slabodka, the Illui could not adjust to the mussar approach and by the time the Yomim Tovim came to a close, he was on his way back to Brisk.

Nearly 20 years later, however, the Meitscheter would admit that he had missed out on a unique opportunity. Rav Yechiel Perr shared the following story:

In the years prior to World War I, the great baal mussar and Rav of Shadova and Lomza, Rav Aharon “Archik” Bakst, was traveling and had to change trains in Lida. Train schedules were not then what they are today, and Reb Archik had to wait overnight for his train in the Lida hub. In the interim, Reb Archik visited the yeshivah in Lida.

Upon entering the yeshivah, Rav Archik was greeted by the Meitscheter, who immediately invited the Rav to spend the night in his home. Shortly afterward, the rav of Lida, Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Reines, arrived at the yeshivah and he too invited Rav Archik. Rav Archik told Rav Reines that he had already been invited by the Meitscheter and said, “The Rav should pasken as to where I should go.” Rav Reines answered, “I pasken that you should go to whomever you wish!” Rav Archik then answered, “If so, I will go to the Meitscheter.”

That night, over supper, the Meitscheter said to Rav Archik, “Repeat to me a shmuess from your Rebbi.”

Rav Archik then repeated an entire breathtaking shmuess from Rav Simcha Zissel of Kelm, and the Meitscheter was overwhelmed with awe. The Yiddish idiom that was used to describe the Meitscheter’s response means, “He grabbed himself by the head!”

Thereupon Rav Archik told the Meitscheter that this shmuess had been said 18 years before, when they were both talmidim of the Alter of Kelm, “…and I saw you leave the beis medrash in order not to have to listen,” Rav Archik said. “So, I decided to accept your invitation for tonight, just in order to repeat this shmuess to you.”

With the Lions of Vilna

After his time in Kelm, the Illui returned to Brisk, but his second stint there was not a long one. Shortly following his return, he received a draft order from the Russian military. Rav Chaim advised him to go to Vilna, where a certain doctor would be helpful in arranging for a deferment. Accompanied by another student of Rav Chaim, Rav Eliezer Silver, he traveled to Vilna to make the necessary arrangements.

Once in Vilna, the duo from Brisk rejoiced at the opportunity to spend time with one of the great Torah leaders of the era.

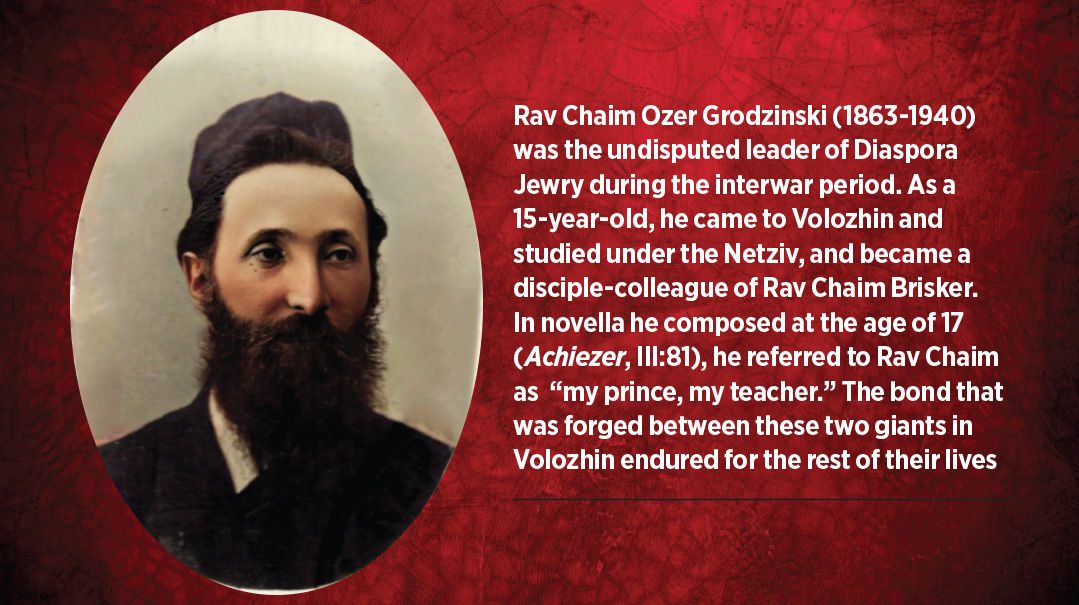

Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski had been appointed to a position on the prestigious Vilna Bais Din in 1887 at the young age of 23, upon the untimely passing of his father-in-law Rav Eliyahu Eliezer Grodzinski. He’d remain there for the next more than half a century until his passing in 1940.

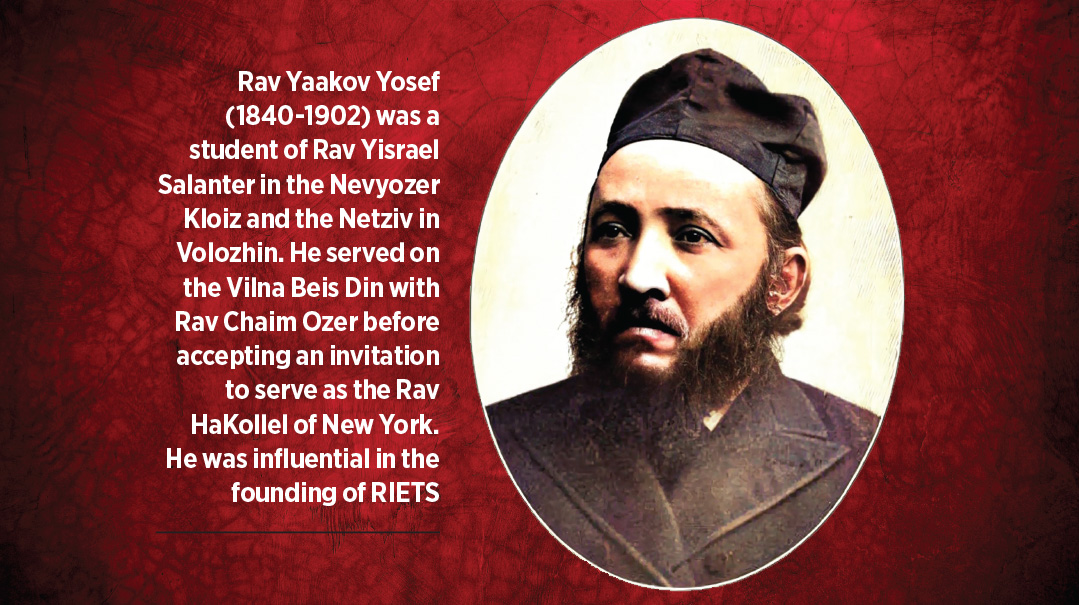

Serving together with him on the Vilna Beis Din during those years were some of the great Torah scholars of the era: Rav Chanoch Henoch Eiges (the Marcheshes), Rav Meir Bassin and later his son-in-law Rav Yisroel Zev Gustman, Rav Yaakov Yosef (later the Rav HaKollel of New York), and the great Rav Shlomo Hakohen, author of the Cheshek Shlomo. His elder brother Rav Betzalel had previously served on the Vilna Beis Din as well and had passed away several years earlier. (The Cheshek Shlomo’s son-in-law was Rav Nachum Greenhaus, rav of the Vilna suburb of Trakai. His progeny continued in the Trakai rabbinate, and that’s where his grandson and namesake Rav Nachum Partzovitz — the future Mir rosh yeshivah — was born.)

In addition to his position on the beis din, Rav Chaim Ozer eventually assumed stewardship of the local Rameiles Yeshivah. He also established a kibbutz (group) of elite young Torah scholars in Vilna. His students included some of the great young minds in the Lithuanian Torah world, whom he helped develop into great leaders. The list includes Rav Reuven Katz (Rav of Petach Tikvah), Rabbi Moshe Shatzkes (Lomza/New York), Rav Yecheskel Abramsky (Slutzk/London/Bnei Brak), Rav Moshe Avigdor Amiel (Antwerp/Tel Aviv), and Rav Shmuel Yitzchok Hillman (Av Beth Din of London).

When Rav Chaim Ozer invited the Meitscheter and Rav Leizer Silver to join this elite group, it was an opportunity they could not pass up. The group rotated between four area shuls so as not to arouse the attention of local authorities, and on Shabbos they would gather at Rav Chaim Ozer’s home to hear shiurim.

In 1899, the Torah community in Vilna celebrated a Siyum HaShas, with the festivities lasting seven days. On each of the seven nights, a celebration was held in a different Vilna beis medrash. Rav Chaim Ozer paid tribute to the Meitscheter by inviting him to say a Hadran in each of the shuls. He began the Hadran on the first night and concluded it on the seventh night, with seven brilliant, self-contained, yet interrelated shiurim that encompassed the entire six sedorim of Shas.

Life in Vilna was very different from that in the smaller towns that the Meitscheter had previously called home. The city boasted the Strashun Library, which housed one of the world’s largest and most important collections of rare seforim and manuscripts. There were also numerous other cultural institutions that provided the Illui and other members of the kibbutz with their first formal exposure to secular subjects.

In truth, the Illui’s thirst for knowledge had exposed him to mathematics from a young age. In a moment of candor with his student Moshe Bitensky, he recounted how as a 12-year-old in Volozhin, he worked out a solution to several difficult problems in trigonometry, without the aid of books or a teacher. His photographic memory allowed him to memorize entire chapters of Russian literature and he devoured complete textbooks in one sitting. Noted biographer and student of the Meitscheter, Zev Rabiner, shared that following the Illui’s death, the noted Vilna scholar Feivel Meir Getz wrote that the world of mathematics had lost one of its leading lights, for had he devoted himself to that discipline, he would have had a podium in one of the world’s most renowned universities.

When he reached marriageable age, the Illui was offered matches with the daughters of great rabbis and wealthy businessmen but refused to consider them. In 1902, he married Chaya Rivka, the daughter of Avraham Abba Rubinitzki, a well-to-do but simple merchant in Ivyanets, a town near Volozhin, and settled there.

After his wedding, convinced that he was unfit to be a teacher of Torah or a community rav, he started a business together with a partner from Minsk. They opened a factory, but the venture was unsuccessful, and in the course of a year he lost a large portion of his money.

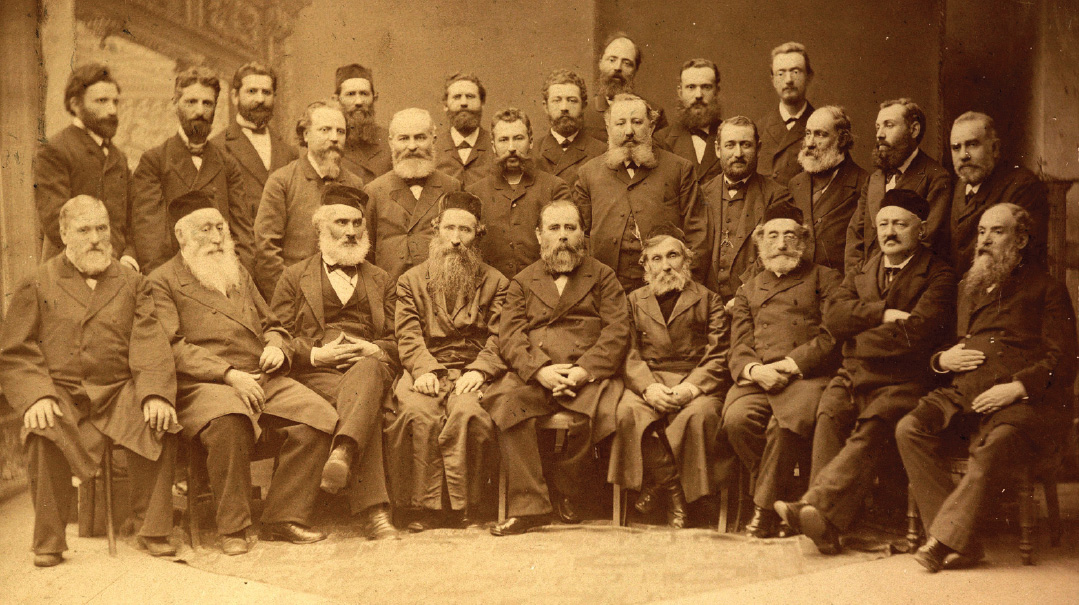

The inaugural conference of the Chovevei Tzion was held in Katowice (presently Poland), in 1884. Seated third through seventh from right: Alexander Zederboim, editor of Hamelitz, Rav Dovid’l Friedman of Karlin, Dr. Leon Pinsker, Rav Shmuel Mohilever, David Gordon, editor of Hamagid. Seated last on left is the great philanthropist and Volozhin alumni, Kalman Zev Wissotsky. Rav Reines was unable to attend due to the lack of a valid passport

Part III: The Lida Years

Revolutionary Rabbi

During this time, a prodigy who’d learned in Volozhin a generation prior to the Illui was making a revolutionary impact on traditional Jewish society.

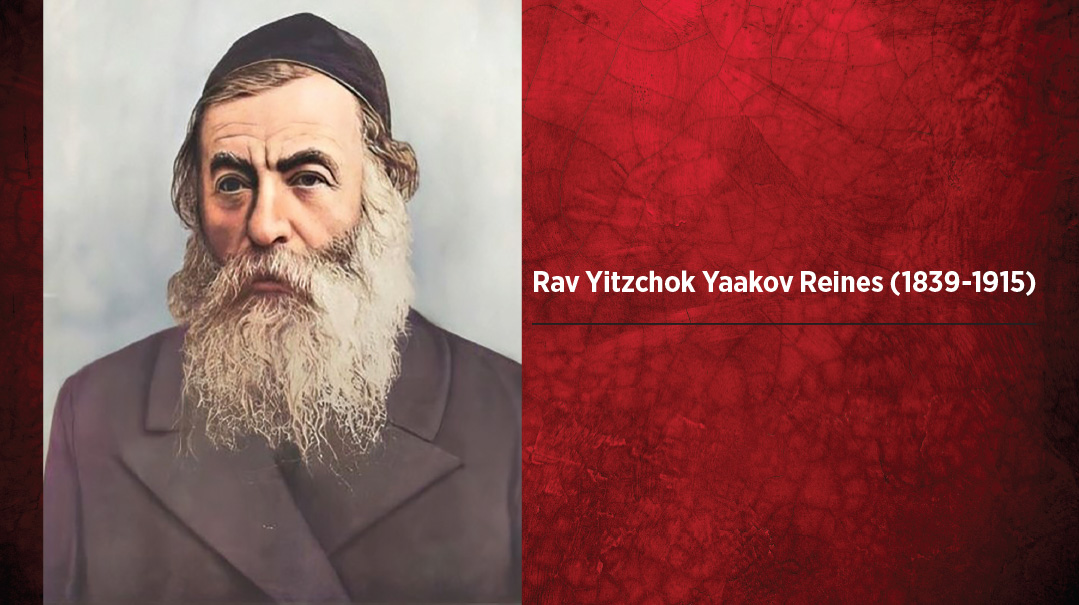

Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Reines arrived in Volozhin from his hometown of Karlin at the age of 15 and studied there under the Beis HaLevi and the Netziv. At the age of 17, he married the daughter of Rav Yitzchok Reisin, Rav of Hordok. The following year saw the publication of Rav Reines’s sefer Edus B’Yaakov, the first of nearly a dozen seforim and countless unpublished works that he penned.

During his years in Volozhin, Rav Reines became attracted to the Chovevei Tzion movement, then led by prominent rabbinic figures such as Rav Shmuel Mohilever and Rav Dovid’l Friedman of his hometown of Karlin. The Netziv was a supporter of the movement as well, though in a more passive sense. In 1902 Rav Reines was instrumental in the founding of the Mizrachi movement, best described by historian Jeffrey Gurock as “an independent Orthodox body within the budding Zionist cause, dedicated to serving as a watchdog organization against the pervasiveness of secular ideas and activities within the Jewish national movement.”

Zionism wasn’t the only area of contemporary Jewish life where Rav Reines was willing to take courageous and even controversial stands. In 1875, he conceptualized the concept of kollel, where young married men would study after their marriage and receive a stipend from the greater community. This vision eventually spawned the creation of the Kovno Kollel, though by the time it was opened several years later, he was not involved in its governance.

Following a stint as the rav of Shviciani, maggid of Vilna, and a short-lived rabbinate in Manchester, Rav Reines assumed the helm of the Lida rabbinate, in what was then part of the Vilna Governorate of the Russian empire. It was there, in 1905, that he made his next bold move, opening a revolutionary Torah institution: Yeshivah Torah Vodaas of Lida, which combined intense Torah learning with general studies. In opening such an institution, he hoped to solve several issues.

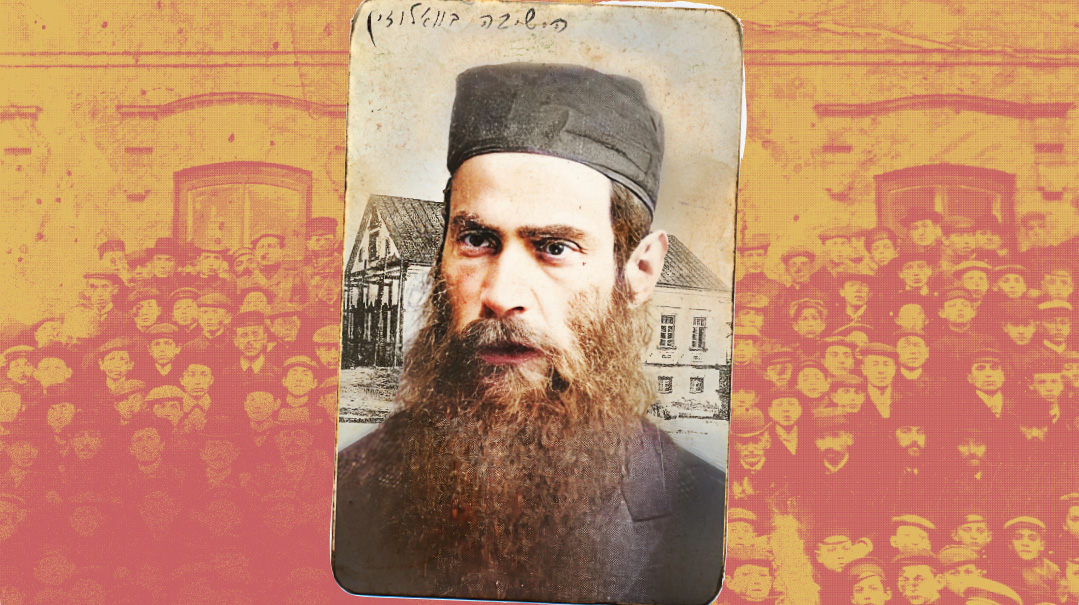

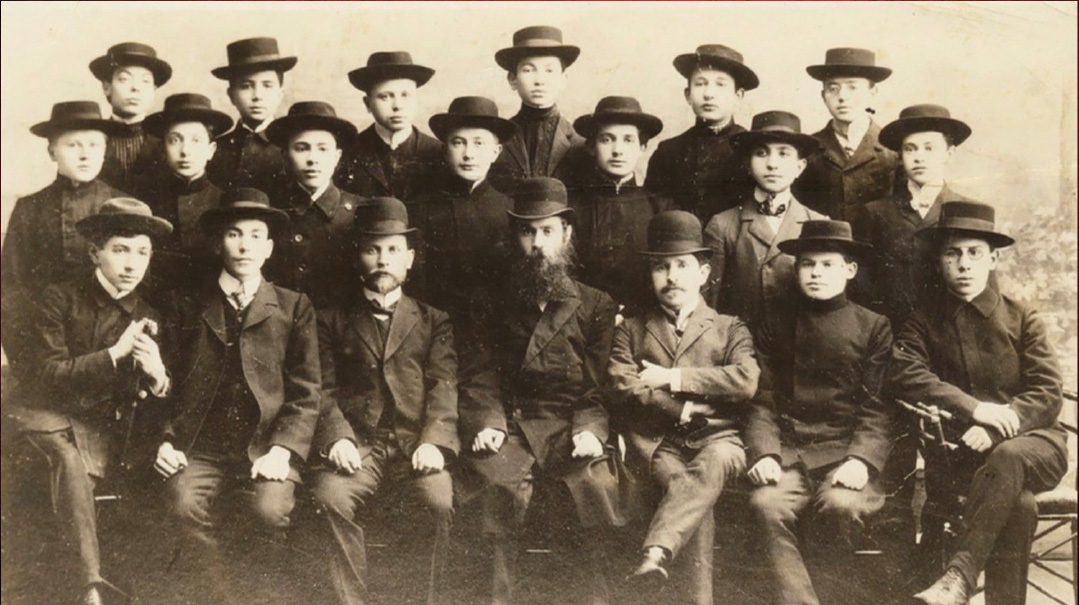

The Meitscheter Illui along with his talmidim in Lida, in 1910

A New Kind of Yeshivah

Growing secularization in the late 19th century greatly eroded the prestige of the Torah and those who studied it. Once-packed batei medrash stood empty, and young Torah scholars could not find women willing to marry them. Rav Reines hoped that he could prove to his young charges the beauty of Torah while attracting them to the yeshivah with a “taste” of secular education. He asserted that his goals were the education of not only rabbanim, but also balabatim who would learn to appreciate the Torah, as well as those who studied it.

Other considerations factored in this decision as well. During the harsh reign of Czar Nicholas I (1825-1855), new laws were enacted requiring rabbanim to perform civil duties such as registering births, marriages, and divorces on behalf of their respective communities. Because this position required fluency in Russian, the vast majority of traditional rabbis could not perform these tasks.

As a result, communities had to hire a rav mitaam or “crown rabbi,” who generally lacked knowledge of Jewish law. Destitute communities had to pay the salaries of both the crown rabbi and the real rabbi, and tension often existed between the two. Rav Reines hoped that his yeshivah would obviate the need for these detrimental crown rabbis, by providing students with the necessary credentials within a yeshivah framework.

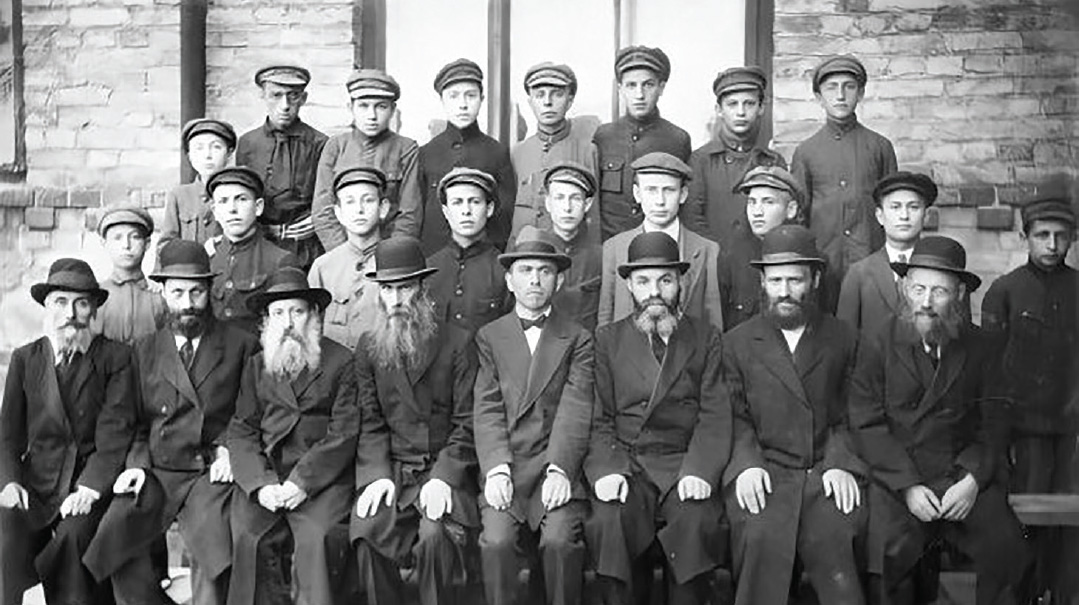

A 1913 photo of the Lida Yeshivah faculty and students

Rav Reines opened Torah Vodaas in the city of Lida in 1905. As the rav of the city, he was able to shore up support from local donors as well as some of the wealthiest Jews in Russia who supported his vision. Marketing materials and memoirs from students make it clear that the yeshivah was in no way affiliated with Mizrachi or any political movement.

Rav Reines also wanted to ensure that it was clear his institution was first and foremost a yeshivah, and that secular studies were secondary. He felt that this message would be best conveyed with the hiring of a gadol as its rosh yeshivah. By then, the Meitscheter’s old friend from Volozhin, Rav Aharon Rabinowitz, had married Rav Reines’s daughter Gila and was serving on the Lida Beis Din. He suggested that his father-in-law hire the Meitscheter for the position, and in 1905, Yeshivah Torah Vodaas of Lida was opened with the 28-year-old Meitscheter Illui at its helm.

Rav Reines also hired a prime student of mussar giant Rav Yitzchak Blazer to serve as its mashgiach: Rav Eliyahu Dov Berkovsky, a cousin of the Meitscheter and a fellow student of his at Volozhin who had also studied in Mir and Slabodka. He had served as mashgiach in a branch of the Novardok yeshivah, but never really took to the austere Novardok approach. It was a different school of mussar that resonated with Rav Berkovsky, and to anyone who viewed the yeshivah’s orderly campus or the shiny buttons on the blazers of its students, it was clear that the “gadlus ha’adam” approach of Slabodka reigned strong in Lida.

Photo taken outside the Lida Yeshivah upon the visit of the great philanthropist, Raphael Getz of Moscow

Deeper Than the Ocean

During the Lida years, hundreds of new students got a close-up view of the famed genius of Volozhin. In his biographical sketch of the Meitscheter, his student Hirsch Leib Gordon wrote of his first encounter with the vaunted Illui:

The first day that I arrived there (in Lida), I encountered in the street a well-built Jew standing upright but walking as if he were in a dreamlike state. A light wind scattered his long, blond beard. I noticed with astonishment that despite the fact that his eyes were wide open, it appeared as though he were sleepwalking. It was a miracle that he narrowly avoided the passing carriages; at times he would bump into fences and telegraph poles. I said to myself: this must be the Illui of Meitschet; and indeed it was.

The yeshivah had four divisions and the Mechinah (High School) had three, peaking at more than 300 students in 1911. At first the Illui delivered shiurim for the yeshivah’s highest class, the elite Kibbutz, which spent the whole day learning Torah. Eventually he was engaged for the eldest post-mesivta division as well. His students, who were considered the aristocrats of the yeshivah, felt proud and privileged to learn directly under the famed Illui.

Torah Vodaas of Lida was housed in a small building that lacked space for all the classes. Therefore, the Illui would deliver his shiur in the attic of a nearby shul. Hirsch Leib Gordon described the scene:

He spoke slowly, in a pleasant voice. His large eyes were wide open, yet they were not focused on any specific area. It seemed that even while he was speaking, he did not cease from being in his dreamlike state.

During the first moments, we all knew what he was talking about, since his remarks were based on the passage of the Gemara that we studied. But as soon as he began to expound on super-fine distinctions, and reveal the deep and hidden foundations of halachah, then one by one we began to lose track of the golden thread he spun to guide us through the Talmudic labyrinth. We were unable to retrace the path of our ascent. Our minds swirled with dizziness.

Asking the Illui questions from rare books that he’d never seen [in an attempt to stump him] was useless. He always managed to give the same answer that the original author gave. Our teacher’s words were deeper than the ocean.

We would rush home and eat our meal in haste and in a state of mental confusion, and then return in order to reconstruct the shiur from the fragments that we remembered. Most students only remembered a fraction of the shiur, in particular the first part. However, the outstanding students remembered everything and were able to understand what our teacher had in mind. After repeating the shiur several times — accompanied by shouting and arguing in Torah — the writers among us sat down and transcribed everything in notebooks.

Yeshivah bochurim from neighboring towns would regularly come to Lida, seeking to talk in learning with the Meitscheter. Even roshei yeshivah from the surrounding region, such as Rav Mottel Katz, the the future rosh yeshivah of Telz, would come spend extended periods of time in Lida just to learn from him and delight in his chiddushim.

The Illui was once questioned by a visitor why he was willing to join the yeshivah in Lida, which was considered of a lower caliber than the upper-tier Lithuanian yeshivahs. “I didn’t have a father or father-in-law who was a rosh yeshivah,” he answered sharply, clearly taking aim at the dynastic yeshivos prevalent during that era.

Quite a few of his talmidim showed exceptional ability in learning, and when Rav Itzele Ponevezher started his kibbutz with only 12 handpicked bochurim, four among those elite students were talmidim of the Meitscheter.

As Great as Ever

Contrary to what one may suppose, even after the Illui took his post in Lida, Rav Chaim continued to speak of his prized student with love and respect.

While the Meitschter was serving as rosh yeshivah in Lida, a conversation took place between Rav Chaim and some of his students in which the Meitscheter was mentioned, and Rav Chaim spoke very highly of him. One of those present remarked that since the Meitscheter had accepted the position as rosh yeshivah in Lida, it could only be assumed that Rav Chaim, a sharp opponent of Zionism and Rav Reines, would treat the Meitscheter coolly.

Rav Chaim retorted, clearly and sharply, “What does one have to do with the other? Because I do not approve of Zionism, must I disapprove of Rav Reines? And if I disapprove of Rav Reines, must I disapprove of his yeshivah? And if I don’t approve of the Lida Yeshivah, must I also disapprove of the Meitscheter? I may be an opponent of Zionism and still approve of Rav Reines. And I may be an opponent of him personally and regard his yeshivah well. And even if I were to think poorly of the yeshivah, the Meitscheter remains as great as ever.”

While there were some notable exceptions, most gedolei Yisrael, even if they harbored no ill will towards Rav Reines, worried about the precedent set by the Lida Yeshivah and viewed it with suspicion.

The Chofetz Chaim kept a watchful eye from nearby Radin and strongly criticized Lida’s progressive measures. When three students in the Radin yeshivah were expelled for a serious infraction, the Chofetz Chaim’s son-in-law Rav Mendel Zaks was asked to intervene on their behalf. The Chofetz Chaim would not budge from his position until Rav Mendel suggested that the rejected boys might instead register at the Lida yeshivah. After hearing that, he agreed to take them back.

Reb Raphael Zalman Levine, the son of Rav Chaim Avraham Dov Ber Levine — best known as “the Malach,” was a talmid in Knesses Beis Yitzchak and later a student of the Meitscheter in New York. He related that his rebbi, Rav Boruch Ber Lebowitz, was so opposed to the Lida yeshivah that he would turn down prospective students if he heard that a sibling had studied in Lida. However, his personal esteem for the Meitscheter remained enormous.

Once, when Rav Boruch Ber’s yeshivah was settled in Vilna during the years following World War I, he was visited by the Meitscheter. While his guest was there, Rav Boruch Ber refused to deliver a shiur. “Both of us learned Torah from ‘Der Rebbe’ (his title for Rav Chaim Soloveitchik), but Rav Shlomo learned from Der Rebbe for a few years after me. Therefore, he heard shiurim from Der Rebbe that I didn’t. Those shiurim probably were even better than the shiurim that I heard, for as we know, as talmidei chachamim get older they get wiser. Therefore it wouldn’t be appropriate for me to deliver a shiur in the Illui’s presence.”

On the day that the Illui arrived, Rav Boruch Ber spoke in learning with him for hours, basking in the Torah of their mutually beloved Rebbi. The two also reminisced about the times they shared in Volozhin.

Something struck the bochurim. Here were Rav Boruch Ber and the Meitscheter, perhaps the two closest talmidim of Rav Chaim, who themselves had been disseminating Torah for many years. Not only had they transmitted their Rebbi’s teachings, they also had produced many of their own chiddushim. Why, then, had neither Rav Boruch Ber nor the Meitscheter published their chiddushim?

For both, the answer was quite simple: “How can we possibly publish our chiddushim when Der Rebbe’s chiddushim have yet to be published?”

Yeshivah in Exile

The guns of August 1914 drastically altered Jewish life in eastern Europe, as the towns and cities of Galicia and the Pale of Settlement were ravaged by the outbreak of World War I. The collateral effects of war weren’t limited to the battlefield itself; many Jews were forced into exile and became refugees, traditional economies were destroyed, and a complete breakdown of communal life resulted in the ensuing mayhem.

The Lida yeshivah’s road to exile was prefaced by tragedy. The yeshivah’s beloved founder Rav Yitzchak Yaakov Reines succumbed to a long illness and passed away on August 20, 1915, at the height of the German offensive in the region. The worsening conditions forced the yeshivah’s administration to execute the yeshivah’s escape during the shivah itself. One hundred and ten talmidim went into exile, and following an extended journey, the yeshivah’s remnants reestablished themselves in central Ukraine in the city of Elisavetgrad (currently known as Kropyvnytskyi).

The Meitscheter was now faced with the full responsibility of managing the yeshivah, both delivering shiurim as well as fundraising. He was assisted by Rav Eliyahu Dov Berkovsky, who accompanied the yeshivah into exile as well. The Meitscheter succeeded in securing funding from donors in the Russian interior, with the bulk of the money coming from the Moscow philanthropist Rafael Getz, son-in-law of Jewish tea magnate Kalman Zev Wissotzky.

The war years were challenging for the Meitscheter and his family, who were often starving. Shortly after they fled, Rav Aharon Rabinowitz (who succeeded his father-in-law as the Rav of Lida) sent his wife and five children to stay with the Polacheck family. The yeshivah paid the Meitscheter a monthly salary of 125 rubles to support his family and another 75 rubles for Rav Aharon Rabinowitz’s wife and children, yet after the war it became known that he had surreptitiously provided the Rabinowitzes with 100 rubles and deducted the balance from his own.

The refugees were ravaged by typhus and two of the Rabinowitz children succumbed to the illness. In an unpublished memoir [lightly edited here], the Meitscheter’s daughter Rose (later Pines) recalled,

During that time each one of us had typhoid fever… After a while the yeshivah had no money to pay the teachers and we were all absolutely starving. Our food consisted of some very thin cereal and a glass of tea with a hard candy, morning and night. Sometimes we — my mother, my sister Sarah and I — took apart bags from potatoes, washed the fabric, and made shawls that we sold. My mother also sold her beautiful trousseau, piece by piece.

One day when my mother and I went to the market to buy or sell something, we saw a farm woman who had a [loaf of] bread to sell. We had not seen bread for at least two or three years. … We all told my mother to keep the loaf for Shabbos.

My mother owned a couple of chickens, so she used to collect four eggs and every Shabbos she gave each one of us a half of a hard-boiled egg and Father used to get a whole egg. He used to complain — why should he have more than the rest of the family?

The Meitscheter (fourth from left) with students and faculty at Tachkemoni in Bialystok, in 1922. Also seen is Moshe Aron Reguer, son of the Brisker Dayan, Rav Simcha Zelig Reguer

Murder and Mayhem in the Streets

1917 brought the February Revolution, soon to be followed by the Bolshevik Revolution and a bloody civil war that caused the yeshivah to be closed. Ukrainian nationalists and other factions carried out pogroms against Jews across Ukraine, and the wave of bloodshed saw what was then one of the greatest massacres of Jews in history. Over 100,000 were killed between 1918 and 1921.

Elisavetgrad wasn’t spared, and the Polachek family hid from the marauders, while friends, neighbors and members of the yeshivah staff were killed during the onslaught. In her memoir, Rose shared more details:

There were 10,000 Jews in Elisavetgrad; they killed 3,000. For three days and nights everyone was hiding in the cellars or somewhere else, but they would not let anybody with children into the hiding places as children could cry [and betray our whereabouts]. All our neighbors brought their children to us, as we also had small children.

My father’s colleague in the yeshivah (Rav Yoel Dovid Kaplan)was killed with his wife and oldest daughter. There were three more children left, two boys and a girl. We took the girl into our house after the pogrom and she stayed with us for several years. My mother wanted my father to hide on his own, but he did not want to.

The Polacheks then fled to Kremenchuk, where several exiled Lithuanian yeshivos were located at the time. The Illui delivered shiurim there to a group of bochurim from various yeshivos, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky among them. Rav Yaakov later described the depth of those shiurim, adding that he was one of only two people there capable of grasping the difficult concepts.

The Kaminetz Mashgiach, Rav Moshe Aaron Stern, whose family was close with the Illui, shared the following story with his students:

During that period, the Meitscheter was so poor that he couldn’t afford a table. In lieu of a table, he took his meals on a large cutting board. This arrangement caused him great discomfort as he had to fold his legs in a painful way each time he sat down at his ‘table’. A few of his students took the initiative to purchase a table on behalf of their rebbi. Upon receiving the gift he asked, “From whom did you purchase this table?” When they responded that they had bought it from a non-Jewish proprietor, he let out a sigh. “What will I answer when I come up to Heaven? They’ll say, ‘Shlomo, you had a cutting board to eat upon, why did you require the luxury of having a table?’ Had it been purchased from a Jew, I could have answered that all I did was help another Jews support himself, but now what will I answer?” It seems that the Meitscheter truly didn’t believe that a table was necessary for his home.

The Jews of Kremenchuk were not spared from the brutal pogroms. Rav Reuven Grozovsky wrote how his father-in-law, Rav Boruch Ber, barely escaped with his life after being badly beaten by the murderous gangs. He went on to share the recollections of Rav Shlomo Heiman (who also miraculously survived a similar rampage):

Rav Boruch Ber reacted by expressing how much more simchah and happiness we must now feel when reciting the brachah of “Asher bochar bonu mikol ha’amim venassan lonu es Toraso — Who chose us from amongst all the nations and gave us His Torah,” because we see now the depths to which a person falls when he has no Torah. Were it not for Torah, it would be possible for us, too, to become, chalilah, murderers and degenerates. It is only by virtue of our Torah that our hands do not spill blood.

Eventually, the Meitscheter was able to obtain permits for his family to travel to Poland. His daughter described the journey.

Our trip, which was supposed to take several hours, took seven weeks, as the trains were short of coal. On the way we stopped and naturally we had no food, but the locals were selling apples and we lived on them. … When we were traveling to Poland my father developed malaria and had a fever. We had to stand almost all the time we were on the train. For the second time in my life, I saw my father cry.

After a while we realized that one of the packages was missing and it happened to be the one that was very important to my father, but not important at all to the person who stole it. It was the (transcripts of the 1,500) lectures that my father had given. After my father died, my brother-in-law collected some of the remaining lectures and had a book published.

The Polachek family settled in Bialystok in 1921, and the Meitscheter taught in the local Tachkemoni school. It was there, in the spring of 1922, that he received what might have been one of the most consequential requests for the future of America’s yeshivah world: an invitation to serve as the rosh yeshivah of RIETS in New York City.

Part IV: The Last Station

Spiritual Frontiers

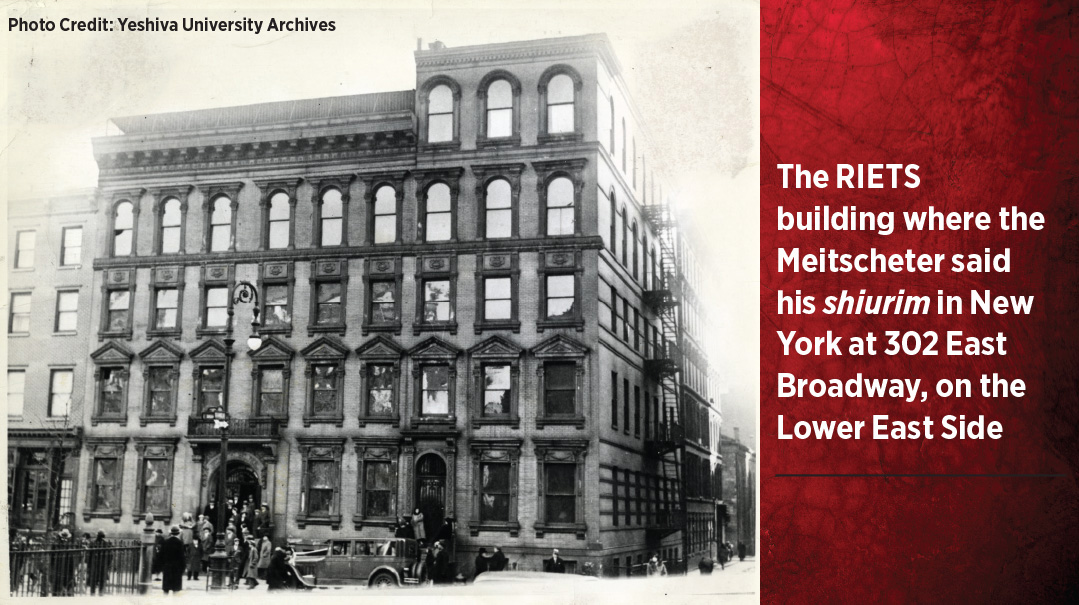

Rabbeinu Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) was founded by a group of Eastern European immigrants on New York’s Lower East Side in 1896. Known simply as “the Yeshivah,” it was the first of its type in America — a place where students could study Torah lishmah (purely for its sake).

Initially, students met at the home of the first rosh yeshivah, Rabbi Moshe Mayer Matlin, a dayan at the beis din of Rav Yaakov Yosef, before moving to larger quarters as it grew in size. For the first 20 years of its existence, the students — a mixture of immigrants and native Americans between the ages of 16 and 21 — heard shiurim from local rabbinic scholars who were the products of the great yeshivos of Lithuania, including Rav Avraham Alperstein, Rav Elazar Meir Preil, and Rav Shlomo Nosson Kotler.

In 1906, the board and roshei yeshivah agreed to add limited secular studies for the students of high school age so they could obtain diplomas and therefore future employment, but the system was not formalized until 1916. (Yeshivah College was not opened until RIETS moved to Washington Heights in 1928.)

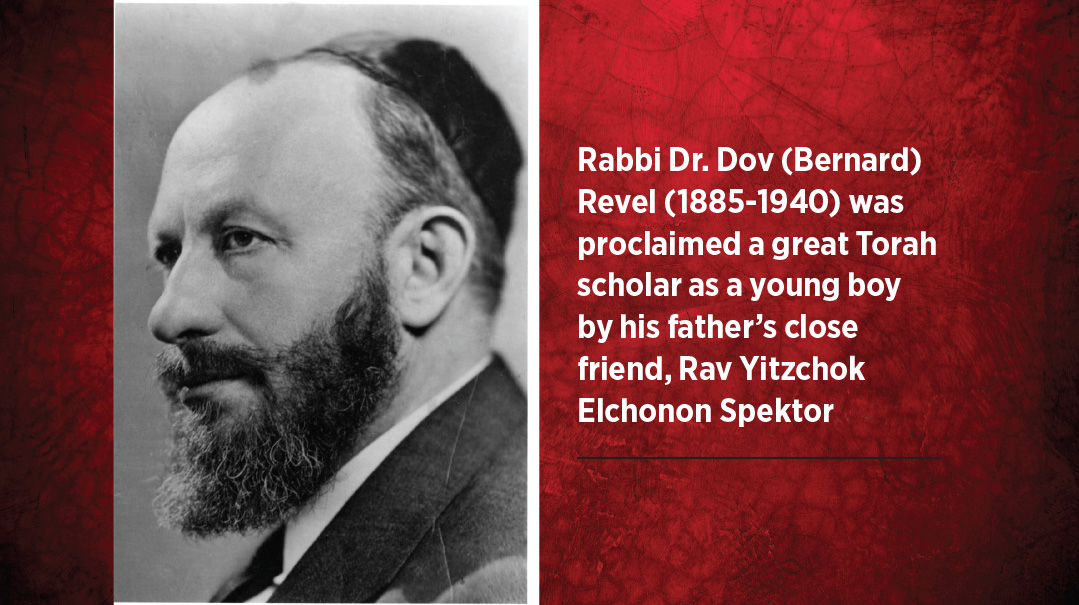

Kovno-born Dov (Bernard) Revel learned in the mussar kloiz of Rav Yitzchok Blazer as well as in the Telshe Yeshivah under Rav Yosef Leib Bloch. In 1905, he was thrust into the turmoil of the Russian Revolution and arrested for his involvement in printing anti-government polemics. While imprisoned in a dirty, dark cell, he gave significant thought to his future and soon after his release, he headed for America and enrolled at RIETS.

The 1923 semichah class at RIETS with the Meitscheter Illui and Rabbi Yisroel Rosenberg. Also in the photo are Rabbis Menachem M. Perr, Mordechai Stern, Isaac Tendler, Yaakov Levovitz, and Solomon Reichman

From the time of its founding RIETS lacked a proper, full-time rosh yeshivah. When the Agudath Harabonim (not to be confused with Agudath Israel) was founded in 1902, the group made the stewardship of America’s only proper yeshivah one of its main priorities, by helping the board of directors to raise funds and taking ownership of spiritual matters.

One of the founders of the rabbinic group was Rabbi Dov Aryeh (Bernard) Levinthal of Philadelphia, who regularly visited and delivered shiurim at the yeshivah. He was immediately taken by Revel’s qualities and in 1909, he hired him to become his assistant. Dr. Revel utilized his years under the rabbinic giant in Philadelphia to familiarize himself with American Orthodoxy, while also earning a doctorate at the newly formed Dropsie College.

In 1915, with the encouragement of Rabbi Levinthal, Dr. Revel was hired as the yeshivah’s first president. In his first major move in his new position, Dr. Revel announced plans to open Talmudical Academy, a four-year yeshivah high school under the auspices of RIETS.

The advent of America’s first such institution would allow RIETS to remain a full-time yeshivah and served as a natural feeder for the yeshivah, which since the start of World War I was no longer receiving many immigrant students. It would also give it a recruitment edge over the Jewish Theological Seminary, which was still nominally Orthodox at that point.

But Dr. Revel was particularly troubled by the lack of a highly qualified, widely revered rosh yeshivah — something he felt limited the yeshivah’s ability to fulfill his vision of building “a blend of Volozhin and Lida on American soil.”

Hiring the Meitscheter would fill that hole and bring great prestige to the yeshivah. The presence of a gadol at its helm could finally lift RIETS to the level of the yeshivos in Europe. This move was also supported by the yeshivah’s new board president, Rabbi Mayer Berlin (the Netziv’s youngest son), who was a great admirer of the Meitscheter.

(For Dr. Bernard Revel, hiring the Meitscheter was just the first step in his grand plan. He hoped to make another splash by offering positions to both Mir Mashgiach Rav Yerucham Levovitz and Rav Moshe Soloveitchik. The ensuing leadership trio would attract the greatest scholars from Europe’s great Torah centers to RIETS.)

After the Meitscheter received the job offer, critics warned him that such a move would be foolhardy, considering America’s reputation as the “treifene medinah.” They told him that nobody in the land of rampant Shabbos desecration and “Yom Kippur Balls” would comprehend, let alone appreciate, the Torah he had to offer.

But as someone who had spent a lifetime bucking trends and avoiding politics — and who’d never quite found a permanent home in the European yeshivah world — the Meitscheter was willing to give America a try. He had always viewed the word through a purely positive prism, and he saw great potential for the development of Torah in America. And so he accepted the position.

To Grab Ah Bissele Volozhin

Once news of the Meitscheter’s hire was confirmed in the summer, the Yiddish press ran story after story touting the great Illui, promoting the arrival of Rav Chaim’s genius student as “a new era for Torah in America.” When he arrived on September 1, 1922, a large crowd gathered to greet his ship in Lower Manhattan.

In The Story of Yeshivah University, Rabbi Gilbert Kaperman explains the impact of the Meitscheter’s arrival on the American Torah scene:

There were other scholars of equal magnitude in Europe and Israel, but Rabbi Polachek was the first European gadol to serve in a professional capacity (as Rosh Yeshivah) in the United States. His qualities and reputation were, therefore, shed upon the Yeshivah, and he helped set the precedent for other scholars of his rank to accept similar invitations in the future. In total, his presence in the Yeshivah reaffirmed the institution’s position as the most important Orthodox institution of Jewish higher learning in America.

The newly arrived Illui rejoiced at the chance to reconnect with several of his old colleagues from Volozhin, including Rav Eliezer Silver, who had arrived 15 years earlier while fleeing Russian military service. Rav Silver was already an important leader in the Agudath Harabonim and quickly invited the Meitscheter to join the rabbinic organization. The two also established a study group for former students of Rav Chaim, where they took joy in engaging in their Rebbi’s Torah and began to collect funds to publish his chiddushim.

The Meitscheter delivered his first shiur at RIETS on September 12th and henceforth several times a week. These shiurim were attended by the elder, more advanced RIETS students who were studying for semichah. Some of his esteemed students at RIETS included Rabbis Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, Nosson Wachtfogel, Menachem Perr, Raphael Zalman Levine, Issac Tendler, Alexander Rosenberg, Yosef Shapiro, Nissan Waxman, Mordechai Stern, Mordechai Schuchatowitz, Israel Tabak, Nathan Drazin, and Elimelech (Max) Wohlgelenter.

The Meitscheter joined a rabbinic faculty that included his fellow Volozhiner, Rav Binyomin Aronowitz, as well as Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyeff (a product of the Slutzk Yeshivah), Rav Shmuel Gerstenfeld (Klausenberg), Rav Yehuda Weil (Radin) and Rav Aharon Dovid Burack (Slabodka / Telz), who also served as the rav of the Volozhiner shul on the Lower East Side.

The Meitscheter’s shiur was also open to balabatim, many of whom would drop everything in the middle of their work day to head over to East Broadway to “chap a bissele Volozhin.” In his 1968 work Natives and Strangers, outlining the history of American Jewry during the past half century, author Judd Teller described the Meitscheter’s impact upon New York’s learned Jews:

Sparse and neat, a narrow beard elongating his high-domed forehead with prominent corners, he resembled Michelangelo’s Moses. His responsibility at Yeshivah was the candidates for rabbinic ordination. They studied in the huge entrance hall which doubled as a synagogue, swaying all day over tomes of ancient law, debating it with themselves, arguing it with others in a singsong voice and with emphatic gestures.

The Meitscheter, at a lectern to the right of the Holy Ark, would stand for hours, eyes shut, almost immobile, only occasionally rifling through a folio that lay before him.

Several times a year he would deliver a public discourse, generally at noon, on a weekday. It was a gala event for the East Side’s Orthodox scholars, whatever their economic station in life. Trustees whose names were embossed in gold in the entrance hall, including the father of the New York Times Sunday Magazine editor, Lester Markel, canceled all their business appointments for the rest of that day; shopkeepers drew their shutters, peddlers covered their wares with tarpaulin and hastened to Yeshivah which, for an hour or two, was jam-packed with an audience whose attention was as taut as a violin string, as they bent their ears with their hands to catch the low voice of the Illui.

As Rav Nosson Wachtfogel related, the Meitscheter’s shiur was on a higher level than anything the America-raised talmidim had ever encountered, and many needed time to adjust. Yet the Meitscheter never displayed an air of superiority toward his students; he treated them as his peers. If a talmid interrupted him in the course of a shiur with a poorly reasoned question, he never showed any irritation. In the gentlest, most loving manner he would say to that talmid, “Ach zolt ihr gezund zain. Listen carefully, please, and you’ll see where your error crept in. I’ll explain again, and I’m sure this time you’ll know what I meant.”

The Meitscheter displayed a deep fondness for each talmid, treating each one like his only son. One year, he invited his student Yosef Shapiro to his Boro Park home for Shavuos. Rabbi Shapiro later described the piety and simplicity of the Meitscheter. When young Yosef was asked to speak in one of the neighborhood shuls, his rebbi sat in the audience like everyone else, beaming with pride as he listened closely to every word.

The Meitscheter was the guest speaker at the chanukas habayis of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath on September 17, 1922. Chazzan Yossele Rosenblatt can be seen at the bottom right, next to a figure who some have speculated is the Meitscheter

He Opened the Doors

Less than two weeks after his arrival in America, the Illui appeared at his first major public event, the chanukas habayis of Yeshivah Torah Vodaath at its new building on Wilson Street in Williamsburg. In addition to meeting many of the leaders of American Orthodoxy, it was an opportunity for the Illui to catch up with one of his top students in Lida, Rabbi Zev Gold, who was now a rav in Brooklyn and among the founders of Torah Vodaath. (It is likely due to Rabbi Gold that the nascent yeshivah carried the same name as the Lida yeshivah: Torah Vodaath.)

Soon enough his influence could be felt in the fledgling American yeshivah world. His packed shiurim, as well as the general enthusiasm felt upon his arrival, proved that America was a place where Torah could in fact thrive.

Historians have pointed out that the hiring of the Meitscheter was the start of a sort of “arms race” between RIETS and Torah Vodaath that resulted in roshei yeshivah such as Rav Dovid Leibowitz, Rav Moshe Rosen, Rav Shlomo Heiman, Rav Shimon Shkop and Rav Moshe Soloveichik being hired from Europe. Once the vaunted Illui made the move, demonstrating his belief that American soil could nurture true talmidei chachamim, the doors were effectively opened for others to make the same leap.

In 1923, Rav Yehuda Levenberg, a close student of the Alter of Slabodka, opened the first out-of-town yeshivah in New Haven, Connecticut. Beis Medrash L’Torah opened up in Chicago around the same time. In 1926, Torah Vodaath opened a mesivta as well as a beis medrash program with 11 students “loaned” by the New Haven Yeshivah. The Meitscheter’s influence was felt there as well.

Rabbi Elias Karp recalled that the Illui would deliver monthly shiurim to the advanced students at Torah Vodaath. Some have even speculated that Torah Vodaath tried hiring the Meitscheter away from RIETS but failed. When Rav Dovid Leibowitz arrived in America in 1927, he formed a close relationship with the Illui and the two could be seen regularly talking in learning together.

While the Illui continued to avoid discussion any political or controversial issue (his views on matters such as Religious Zionism remain unknown), he could and did take a firm stand when when he felt it was warranted.

In his memoirs, Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyeff relates one such issue. In 1924, Dr. Revel invited the gaon Rav Chaim Heller to deliver a series of lectures at Yeshivah University on the topic of biblical criticism. Nobody was better equipped than Rav Heller to tackle the hot button, flavor-of-the-day issue that had swept through European universities, and to refute the claims made by academics — many of whom were known anti-Semites whose sole motivation was to besmirch the words of the Torah.

The rebbeim at RIETS were incensed by the invitation. True, their young talmidim were familiar with the subjects that Rav Heller would raise, but they were far removed from the critical elements and had no reason to be subjected to lectures that raised questions about the validity of certain portions of the Torah. Obviously, Rav Chaim Heller would present them with all of the answers (in a most dazzling display of genius), but the rebbeim worried that the students were unequipped to follow the difficult sequence and might be just left with the questions raised by the Bible critics — none of which would have crossed their mind had they not attended. Instead, they proposed that Rav Chaim Heller (whom they greatly respected) deliver Talmudic lectures like other visiting rosh yeshivah.

When the Meitscheter heard about this issue from Rav Poleyeff, he led his fellow rebbeim to protest the issue with Dr. Revel, resulting in the cancellation of these lectures for the younger, less advanced students.

The Meitscheter can be seen behind Dr. Revel above the New York State flag at the far left of this photo (from the 1927 cornerstone laying)

Acclimating to America

As a new arrival in America, the Meitscheter also had adjustments to make and unfamiliar experiences to integrate. He once stood mesmerized at the sight of children playing ball on the early Yeshivah University campus on East Broadway. When the boys questioned his transfixion, he replied, “Why were we denied such pleasures growing up in Europe? Why did they not let us play ball as children? Had we engaged in sports, we still would be the same Torah scholars we are today and would have also enjoyed a pleasant childhood!” (Rabbi Mayer Berlin relates a similar story as having occurred back in Europe.)

There was also the matter of learning English — but that did not pose much of a challenge for his towering intellect. When the Meitscheter arrived in America, he boarded with a local family until his wife and children came the following summer. Years later, Rav Nota Greenblatt met the man who had hosted the Meitscheter and heard from him as follows: A few weeks into his stay his host noticed the Meitscheter reading the New York Times from cover to cover. So he asked him, “Vos heist, what is this?” The Meitscheter responded, “Ich hub farshtanen yeden vort, I understood every word.”

Rav Nota continued, “You know what that means? Six weeks! That’s all it took for the Meitscheter to master the English language. Do you understand who he was?”

His students at RIETS would amuse him by handing him a page from the newspaper with baseball box scores to glance at. After he scanned it for a few seconds, they would test him on every single statistic — which he was able to repeat effortlessly.

Professor Nathan Klotz, who studied in Slabodka and Slutzk before coming to New York, remembered the Illui once telling his students that the Rambam’s Mishnah Torah was the greatest sefer ever written. When questioned how the Rambam could have penned a more important work than those written by Rishonim who preceded him, the Meitscheter: “The idea that one cannot be greater than his predecessors is true, but only when restricted by natural boundaries. The Rambam was so great — he defied the natural order of history — that he cannot not be judged according to the character of the generation he was born into.”

Beyond the novelty of his incredible mind, having a rosh yeshivah of the Meitscheter’s status brought great prestige and honor to RIETS. Almost every rosh yeshivah who visited America between 1922 and 1928 delivered a shiur at the yeshivah. Among them were Rav Avraham Yitzchok Hakohen Kook, Rav Avraham Dovber Kahana-Shapiro (the Dvar Avraham), Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, Rav Meir Shapiro, Rav Meir Don Plotzki (the Kli Chemda), Rav Isaac Sher, Rav Avraham Yitzchok Bloch, and Rav Boruch Ber Liebowitz.

Following his shiur at RIETS, Rav Kook wrote as follows:

It truly was a great joy for me when I lectured in the yeshivah, and I was amazed to see that even in this country the Jewish people are not forsaken. Thank G-d, there is now an institution here in America from where instruction will go forth to Israel. It will be guidance based upon the true and holy Torah, fear of G-d, and service of G-d.

Many of the Meitscheter’s colleagues in the Agudath Harabonim had long given up hope that America would produce its own rabbinic scholars and even conceded their own children’s chance to receive a proper chinuch. The Illui did not agree. He involved himself closely in the chinuch of his children and was never above sitting down and helping them with homework. The generations of G-d fearing Jews and multitude of rabbis (past and current) who descend from the Illui and his children Rose (Pines), Sarah (Goldberg), Libby (Mowshowitz), Dr. Harry and Dr. Abraham are a testament to the efforts and abiding hopes of the Illui and his wife.

When Rav Leizer Yudel Finkel arrived in New York on his first trip to America as Mir Rosh Yeshivah in 1926, he went to visit his friend the Meitscheter at RIETS. During the course of their conversation, he told his host that he felt that had erred in leaving Europe, because had he stayed, he could have become one of the most prominent roshei yeshivah there. The Illui smiled and replied to Rav Leizer Yudel: “Had I been a European rosh yeshivah, I would be in America now too (fundraising for my yeshivah like you are)!”

Even while living in New York, where he was among America’s most distinguished rabbis, he was a paradigm of humility. The Meitscheter once declared that he would love to settle in Eretz Yisrael and take up the position of a Gemara teacher but couldn’t: “The problem is that I don’t know Hebrew.” To which one of his good friends replied, “How do you know what you know or don’t know? You also think that you don’t know how to learn!”

A historic picture taken at the 1925 installation of Rav Eliezer Silver as rav of Springfield, Massachusetts in 1925. Front row, left to right: unidentified; Dr. Samuel Friedman; Rabbis Bernard Revel; Yisroel Rosenberg; Moshe Zevulun Margolies (Ramaz); Eliezer Silver; Bernard Levinthal; Sheftel Kramer; Baruch Epstein (author of the Torah Temimah). Between Rabbis Rosenberg and Margolies is Rabbi Mayer Berlin. Between Rabbis Levinthal and Kramer is Rav Yehuda Levenberg. In the back, extreme right, is the Meitscheter Illui, with Rav Yehuda Leib Forer to his left

A Premature Sunset

May 8, 1928 was a joyous day for the Meitscheter. Donned in Shabbos finery, he traveled in an automobile together with Rav Eliyahu Gordon and his son Hirsh Leib to City Hall, where Rav Boruch Ber being honored upon his arrival in America by NYC Mayor Jimmy Walker.

When they met, the Illui was excited to reconnect with Rav Boruch Ber and invited him to come deliver a shiur to his talmidim at RIETS, which he accepted. Two weeks later, Rav Boruch Ber and the Illui delivered dazzling shiurim to more than a hundred rabbanim at the Agudath Harabonim convention in Belmar, New Jersey which was followed by a shiur the following week at RIETS attended by a who’s-who of bnei Torah in New York.

Little did the Meitscheter know that a few weeks later, the great talmid of Rav Chaim Brisker would be eulogizing him.

A blood infection due to an abscess in a tooth quickly spread throughout his body, taking him from this world on July 16 / 28 Tammuz at the age of 51. It is told that he could not afford to be seen by a dentist right away because he had refused to accept his salary from RIETS until all the other rebbeim were paid, a move reminiscent of Rav Chaim, who refused to sleep in his own home after the 1895 fire in Brisk, until all the local residents had roofs over their heads.

A massive levayah was held for the Meitscheter outside the yeshivah, on East Broadway. In addition to a moving hesped from Rav Boruch Ber, leaders of the Agudath Harabonim, fellow roshei yeshivah and students spoke. Even after a heat wave scorched mourners during the two hours of eulogies, thousands marched across the bridge into Queens, en route to the burial at the Mt. Judah Cemetery.

The rav of Pittsburgh, Rav Moshe Shimon Sivitz, eulogized the Meitscheter with the words in Parshas Ki Sisa, “And Moshe didn’t know that his face had become radiant when He had spoken to him.” The pasuk doesn’t say, “And Moshe didn’t see that his face was radiant.” Rather, his humility was such that it seemed as if he didn’t know. He didn’t think anything of himself even though his face shone. When he spoke to Klal Yisrael, his face was uncovered and radiant. As a leader he “taught Torah to Am Yisrael.” But when Moshe finished the shiur, he didn’t consider himself any better than other people — “and Moshe returned the veil to his face!”

This was how the Meitscheter conducted himself, Rav Sivitz said. When he delivered a shiur, he was the esteemed rosh yeshivah. But when he sat down, he would tell everyone else, you go first.

In his tribute, Rabbi Meir Berlin wrote, “It was impossible to know the Illui and not be overwhelmed by his greatness. Everyone who came in contact with him had to admit that his abilities were extraordinary. The only person who was unaware of this was he himself. He did not know himself. For as great an illui as he was in Torah, he was a still greater illui in character.”