A Few Minutes with Brig. Gen. (res.) Assaf Orion

"Iran is fighting a long war, and declaring victory is premature"

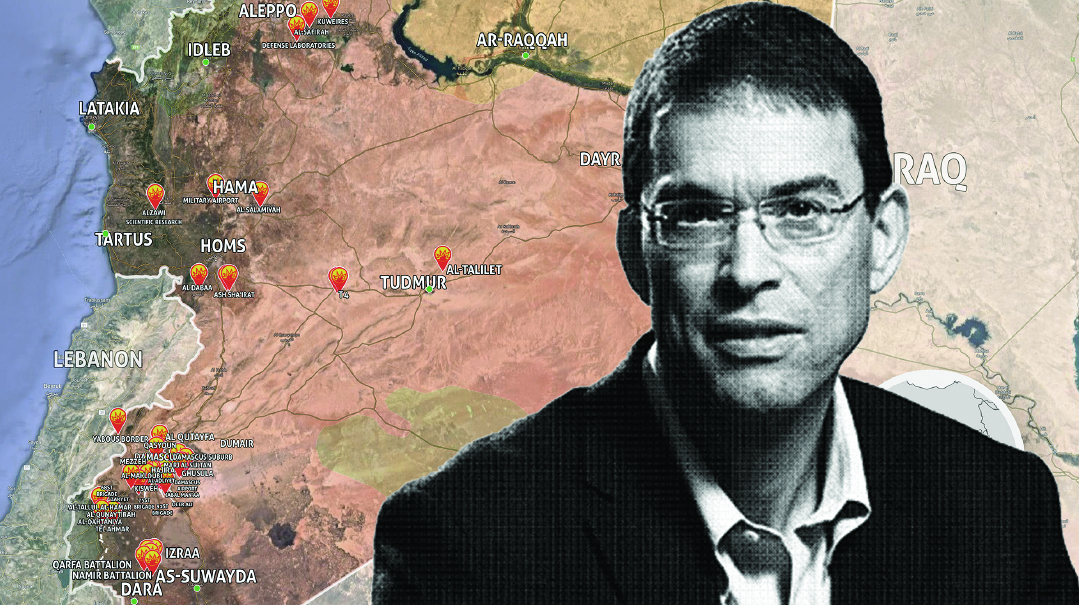

As the international media spotlight focused on the political drama in Washington last week, the warring sides in the Israel-Iran conflict were focused on Syria. Dozens of explosions rocked the eastern part of the country as Iranian proxies and Syrian military facilities were attacked, with dozens of fatalities.

Widely attributed to Israel, the air strikes were likely just the latest act in a years-long Israeli campaign to prevent Tehran from entrenching itself on the country’s borders. But the echoes of the explosions in Syria were meant to be heard in Washington and Europe too. As the Biden administration declares its interest in reentering the nuclear deal with Iran, both Iranian and Israeli moves are part of a strategy of exerting leverage in upcoming negotiations.

In a conference call facilitated by MediaCentral and in follow-up emails, Brig. Gen. (res.) Assaf Orion, a senior fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies, detailed the context of the latest strikes, spoke about the Trump administration’s success in establishing deterrence vis-à-vis Iran, and compared both Israel and Iran’s “slow-cooking, not stir-fry” approach to war-making.

If these reported airstrikes were carried out by the IDF, where do they fit into the wider picture of Israel’s campaign against Iran?

What we’ve heard is that there were dozens of strikes at Boukamal and Deir ez Zor in eastern Syria, reportedly including Iranian Revolutionary Guards targets, Afghan and perhaps Iraqi militias, and possibly Syrian army units.

The wider context of these strikes, which were about 600 kilometers away from Israel, works in several layers. In August last year, the IDF said that since 2017, they’d struck over 1,000 targets across Syria. So that has been happening every two or three weeks for the last few years, and we can plot those attacks using open sources from Syria, to see what the IDF strategy is. Many of those attacks are on Syria’s Golan front with Israel, to stop Iranian proxies entrenching there; others are along the Euphrates, Iran’s supply lines into Syria, since logistics plays a central role in fighting far from home; and third, against command and research facilities around Damascus and Aleppo.

Wherever these proxies are, the Iranian art of war is to use other people's lands and use foreign militias as cannon fodder, so proxies are equipped, trained, and supported by Iran. Israel understands that if they wait, they’ll face another organization prohibitively strong like Hezbollah, so these strikes are the latest act in the long campaign to roll back Iran.

You say that we’ve gained years of peace by the covert struggle with Iran, but are we not worse off for waiting, because there are now proxies in addition to the nuclear threat?

Iran’s proxy warfare is a parallel path to the nuclear, and they are mutually reinforcing; but even before the nuclear program became famous, we began feeling Iran’s work in Lebanon and among the Palestinians. Think about the long years in Lebanon since 1982 and the mid-1990s terror wave. Much of it is courtesy of Tehran. In other words, it’s not as if we have a choice — proxy warfare doesn’t stop if you focus on nuclear only.

So if despite years of Israeli strikes, Iran is still entrenching itself in Syria, Yemen, Iraq, and beyond, does that mean that Iran may be losing battles but winning the war?

The answer is that Iran is fighting a long war, and declaring victory is premature. It accumulated achievements over the years, but we’re still here, aren’t we? A nuclear-ready nation can produce nuclear weapons within three to five years, so if you assume that a strike rolls back their capabilities to zero, which is a fantastic result, within several years they’ll be at the same point. Say Israel had struck in 2005, then by 2010 they would have been back to the same place. So they are playing for attrition, not for decision, and so are we. Israel focused on Syria, and there it has set the Iranian plan back for years, and made Iran and its proxies pay dearly for trying. They continue, and so do we.

As the US administrations change, what successes did the Trump team have that Biden’s people should be following?

Trump gave the Iranians the impression that he was unpredictable, so they were very cautious in attacking the US. Iranian Revolutionary Guards head Ismail Qaani was running around trying to restrain Iran’s proxies. Until Soleimani was killed in 2019, the Iranians had doubts that the US would use its military capabilities against Iran, but that strike came from left field — it changed their calculus about the US. On the Iranian side, all of their steps including enriching uranium, were to accumulate chips for negotiations. And everyone, probably including Trump himself, expected that the maximum-pressure campaign would lead to negotiations — the question was under which conditions.

The new administration is filled with people who designed the Iran deal, and it would be good to see that they have “debriefed,” to use an army term, and come up with better arrangements to deal with Iran’s regional aggression, not just going back to same ones from the Obama era. Gossip has it that the Mossad chief is in Washington now, I guess engaging with the incoming team to try to get their points across.

So how should Israel go about making its case to a new administration that is committed to getting the Iran deal back on track?

Israel has to make the point that when it comes to aviation security, for example, post-9/11 there is a wide margin of error for security. We can’t bring liquids on board because they could be a risk. So how come with Iran, whatever technology has a possible civilian use is kosher? It’s like allowing someone to bring a gun onboard because of their Second Amendment rights. Iran has mastered most of the technologies needed for nuclear weapons, and we all know what these developments are for — to gain a military capability.

Another point is that the Saudis won’t tolerate a situation where Iran has nuclear weapons and not themselves. Do we really want to test cold-war theories of deterrence in a Middle East known for intolerance and instability?

One of the Trump administration’s biggest successes were the recently signed Abraham Accords between Israel and Arab states. Do they mean that Israel will now openly cooperate with the UAE and Saudis to oppose Iran?

I think that this time it will be easier to come to the Biden administration together, but Israel is usually more interested in the deed than in the tale, and traditionally attentive to its partners’ sensitivities. For their own reasons, I don’t see the Gulf States becoming bellicose towards Iran. It’s not their way nor in their interest.

Finally, does Europe, and for that matter the Biden administration, have the stomach to really confront Iran, or only for “deterrence theater"?

There are tough choices down the road. Iran always tries to draw a false choice between concessions (which in the long term will allow it to go nuclear) and escalation to war. War is not an attractive option, including to Iran. Democracies have their public to answer to, and Iran’s regime outlasts their governments. This time around, the incoming team is Obama’s team, so they know the ropes. Hopefully, rather than trying to reenter the same river, now bygone, they will capitalize on the lessons learned from last time, and won’t be out-negotiated.

But at the end of the day, as committed as US administrations may be to stop Iran, America and Europe are less threatened than Israel by a potentially nuclear Iran. So Israel needs to show its partners that a nuclear Iran is not just Israel’s problem, but a global one.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 845)

Oops! We could not locate your form.